Why Prostate Cancer Is Taking a Deadlier Toll on Black Men

A quiet room inside the Moncrief Cancer Institute fills with conversation, concern and courage. It’s not a clinic or hospital ward but a support group. A bright room with white walls and wooden chairs in a circle with 12 Black men sitting together share their journeys navigating the rises and falls of prostate cancer. Stories are shared to reflect the crisis that has long been ignored.

Globally, Black men are disproportionately affected by prostate cancer when compared to other men, according to the National Institutes of Health. According to ZERO Cancer, a nonprofit organization in Alexandria, Virginia.

- One in six Black men will develop prostate cancer; compared to one in eight for men overall.

- Black men are 1.7 times likelier to be diagnosed with prostate cancer, compared to White men.

- Black men are 2.1 times likelier to die from prostate cancer, compared to White men.

A study conducted to evaluate patterns of diagnosis, treatment and outcomes for prostate cancer patients from January 2019 to December 2023 found that men of Black descent aged 65 to 84 were diagnosed with stage III prostate cancer, according to the National Prostate Cancer Audit. Being diagnosed that late in the game only allows for a 37% distant survival rate after five years of diagnosis.

“We see it all the time,” said Dr. Solomon Woldu, a urologic oncologist and associate professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

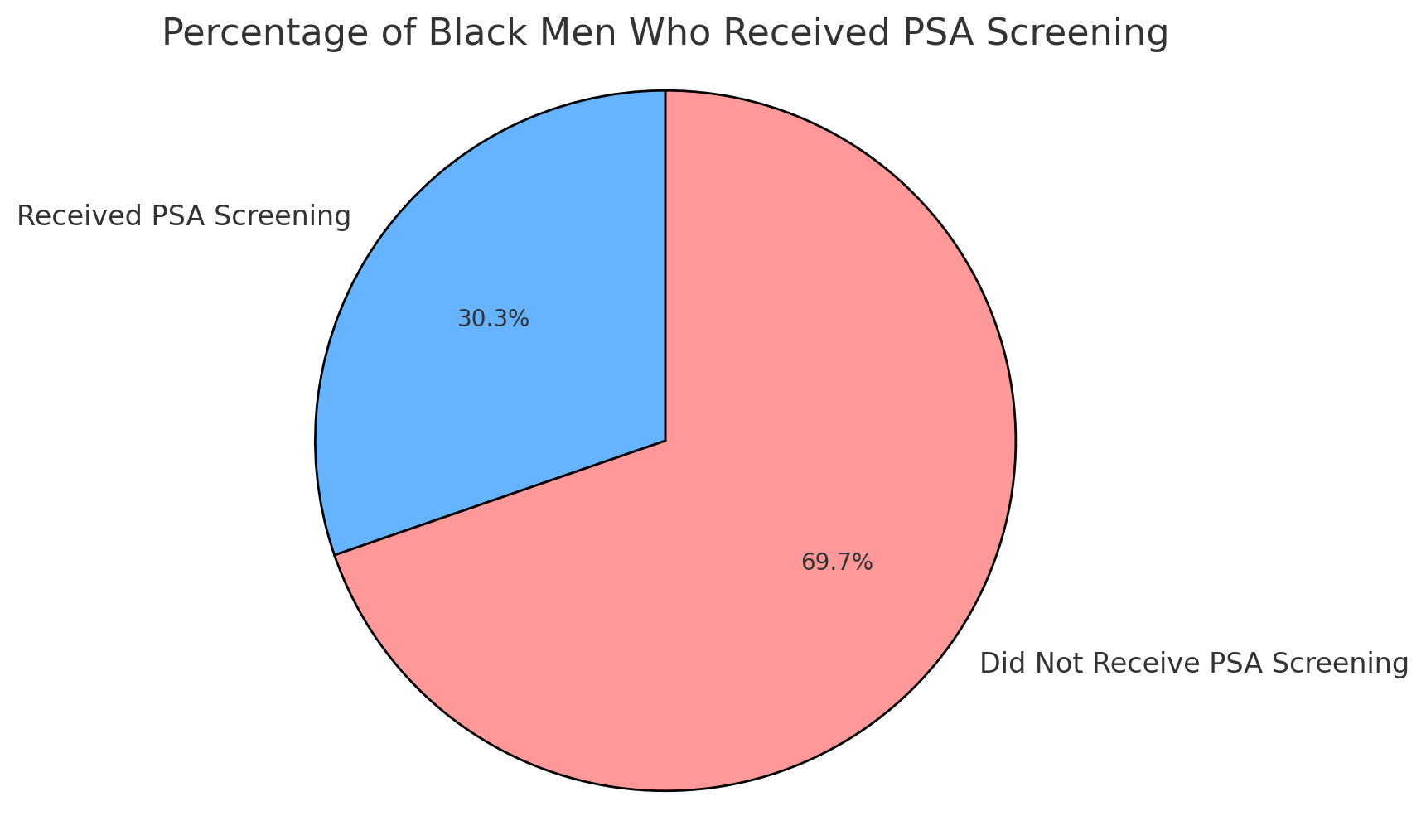

Part of the problem lies in early detection. Prostate-Specific Antigen, known as PSA, is a screening test designed specifically for early detection. Although they are most at-risk for developing prostate cancer, only 30.3% of Black men receive PSA screening, according to the National Institute of Health.

This disparity is blamed on factors ranging from limited access to medical resources, racial bias in clinical settings and generational mistrust, which correlates with the lack of screenings, according to Discrimination and Medical Mistrust in a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Sample of California Adults by Mohsen Bazargan, Sharon Cobb and Shervin Assari.

“Black men are more likely to be diagnosed later and with more aggressive forms of the disease.”

Dr. Solomon Woldu

Why?

The late Dr. Johan Galtung addressed this in his structural violence theory, which examines the indirect harm inflicted upon individuals and communities through unjust social, political or economic systems.

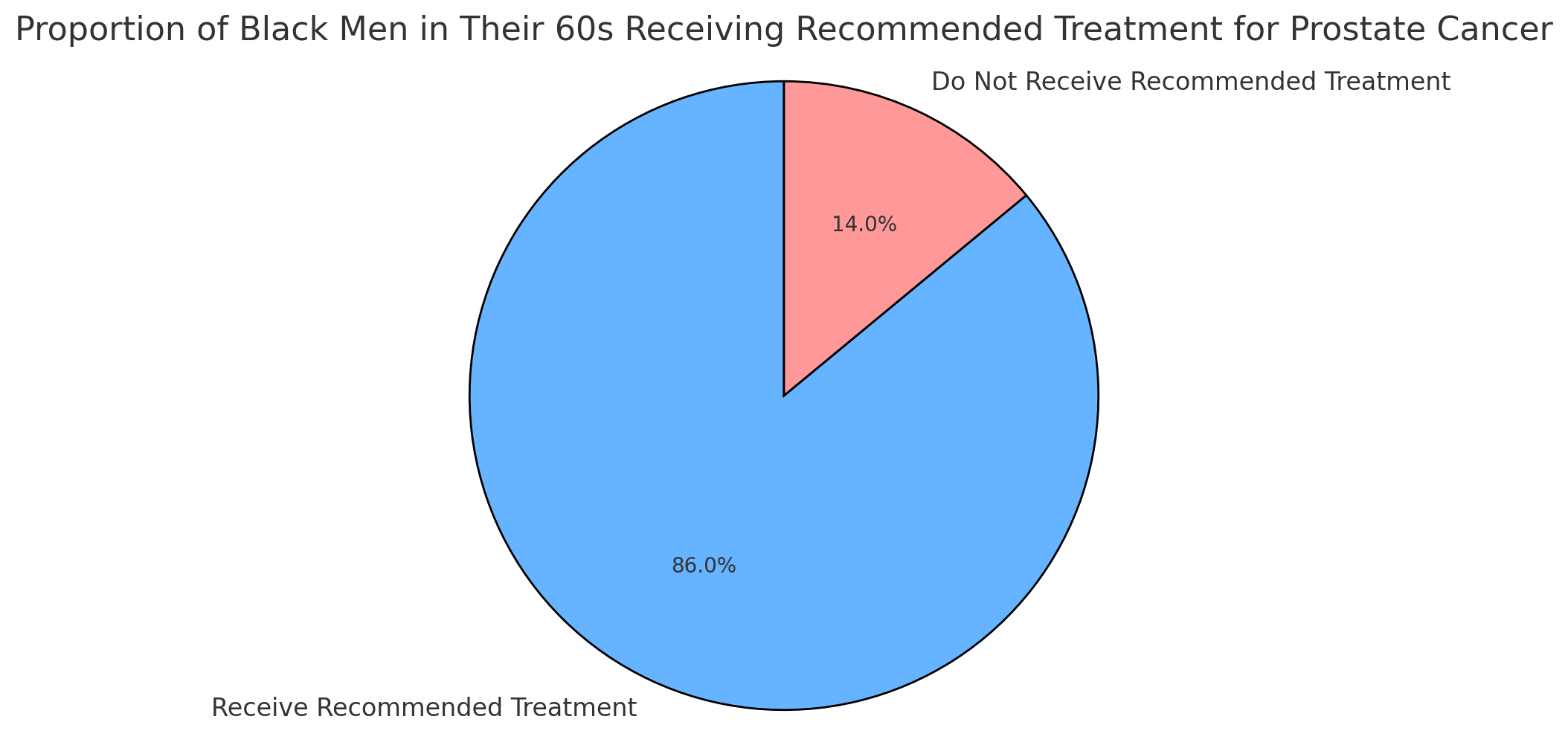

It reflects on how seemingly unrelated structures like where people live, the kind of insurance they have or how they are treated by healthcare providers can contribute to deadly consequences. Structural violence is complex and solutions must be multifaceted. For example, bridging the gap in healthcare disparities is important, but even when Black men are diagnosed, they're still 14% less likely to receive recommended treatment compared to White men.

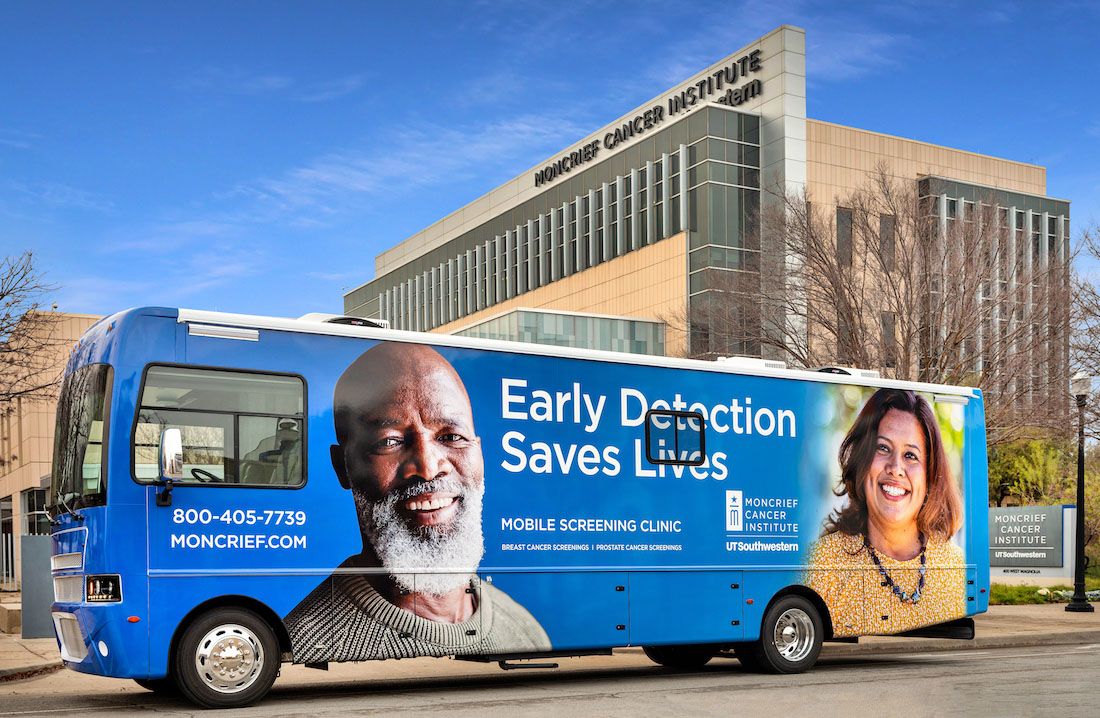

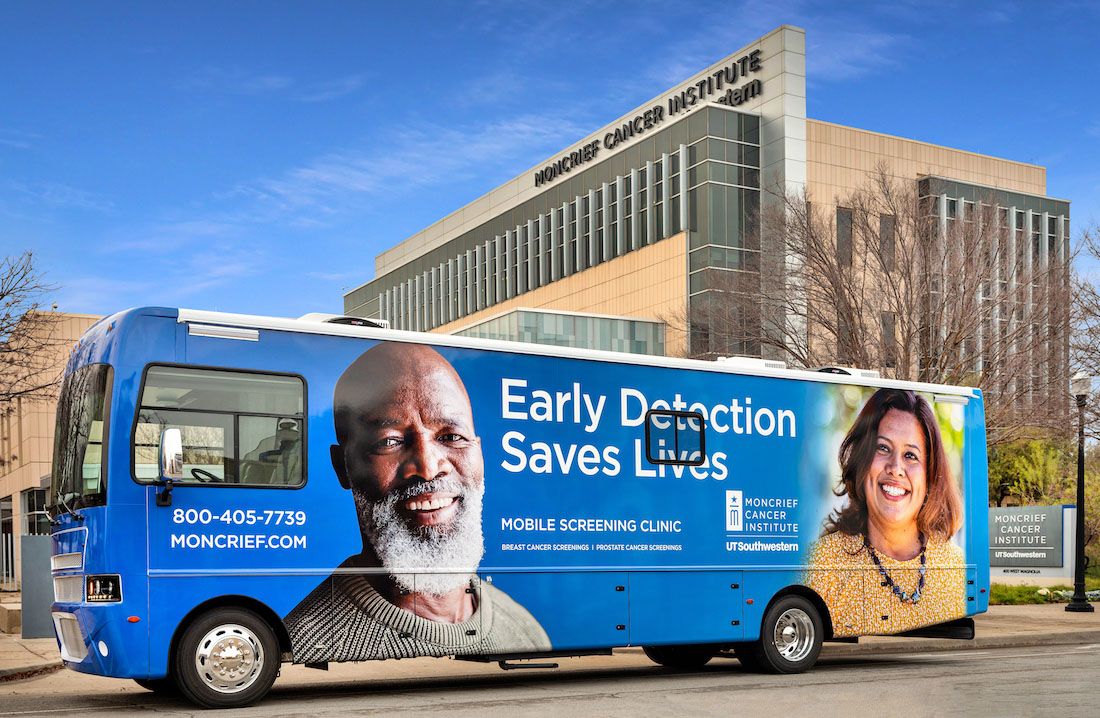

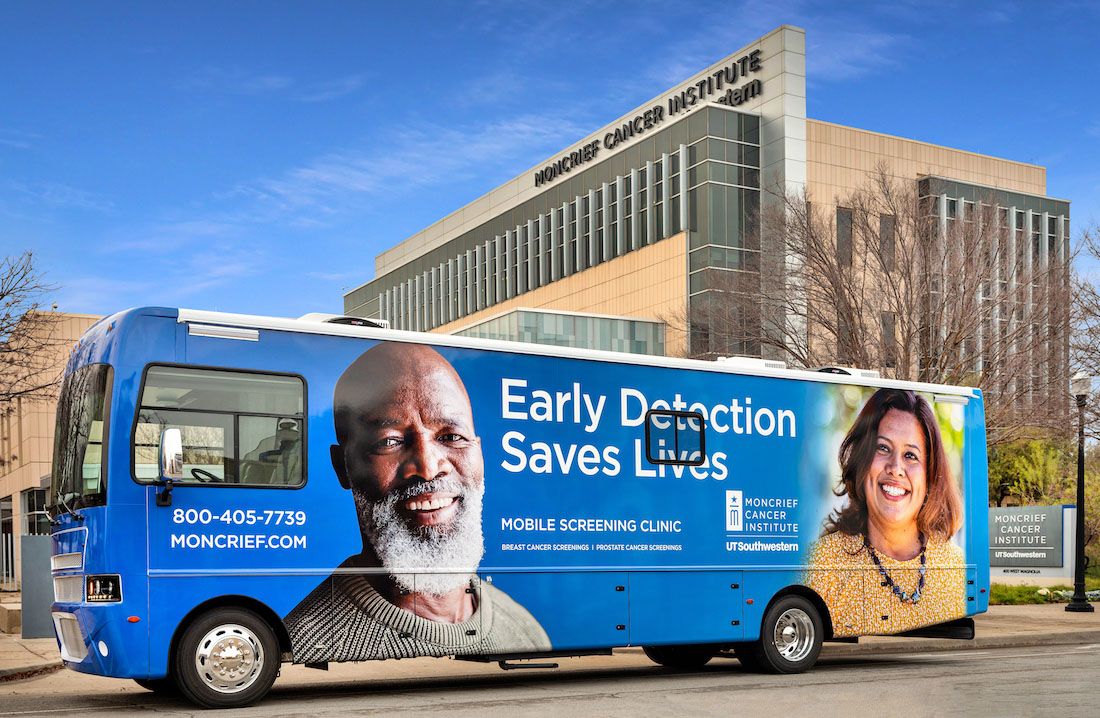

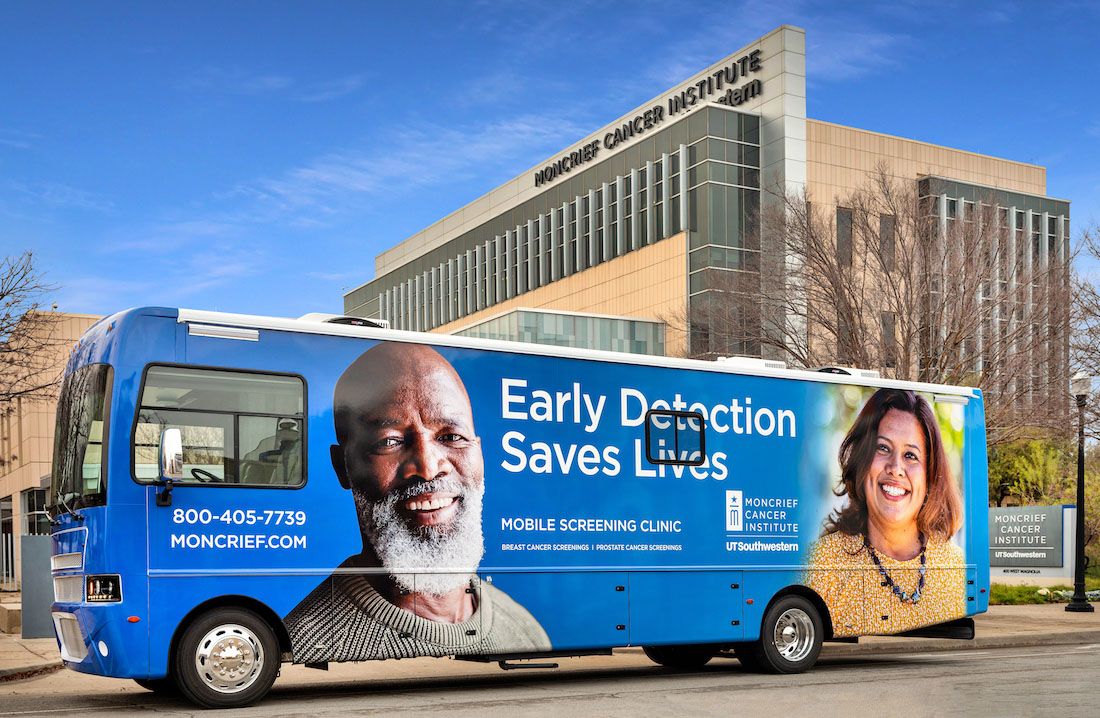

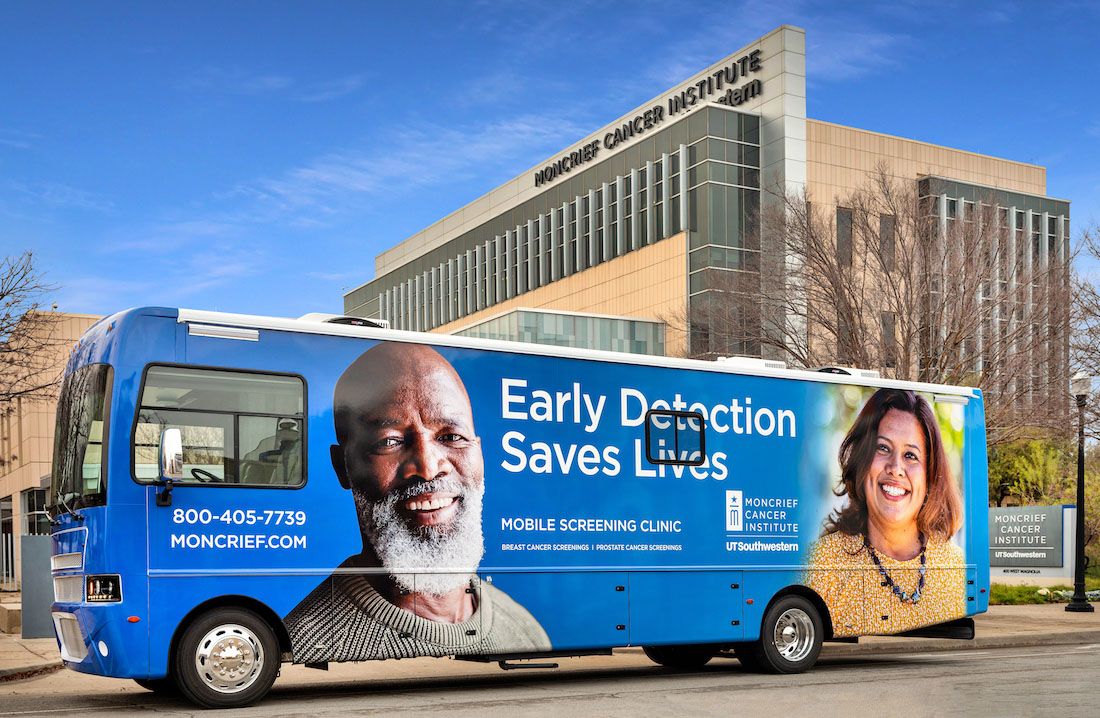

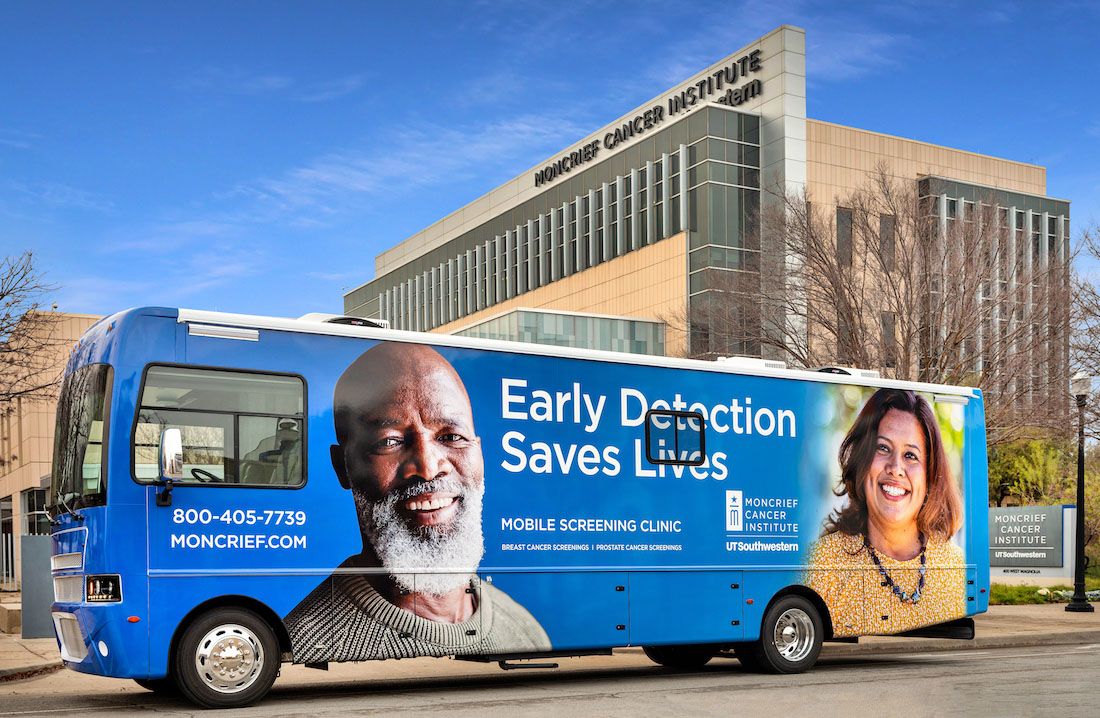

Robert Hernandez, an ambulatory registered nurse at the Moncrief Cancer Institute has taken a different approach. Every third Monday of the month, he hosts this support group previously mentioned, fostering a safe environment for these men to be vulnerable in their struggles. He also coordinates mobile screening events for those who don’t have access to transportation or cannot get to the institute themselves.

“We know that many men aren’t coming in for regular checkups,” Hernandez said. “So we go to them. Churches, barbershops and community centers. Wherever they feel safe.”

Moncrief offers free PSA screenings and blood tests to help address one of the most common barriers: financial instability.

Their recent collaboration with the Texas Center for Urology has made these screenings more frequent and accessible.

Cultural silence is a deafening epidemic that clouds the medical landscape. Black men feel the need to stay silent about their struggles and revert to traditional ways of ‘being a man.’ An alarming statistic is presented by the American Cancer Society: approximately 12% of all new prostate cancer cases in the U.S. will result in deaths among Black men.

This is the sign we should see to push cultural competence programs in medical schools and hospitals across the country. Going to the doctor should feel safe for every individual, not just those who are within the medical practice standard.

Dr. Rick Kittles lecture at Ohio State University on Race, Ancestry and Genetic Diseases. (Center for Genetic Medicine)

Dr. Rick Kittles, an established geneticist and founding director of the Division of Health Equities at City of Hope, has launched research on the genetic factors contributing to prostate cancer disparities.

His work highlights that men of West African ancestry are more likely to carry specific gene variants associated with aggressive forms of prostate cancer.

“Genetics absolutely play a role,” Dr. Kittles said in a 2019 interview through the Cancer Network. “We’ve identified ancestry-linked biomarkers that can increase the risk for earlier and more aggressive prostate cancer among Black men. But addressing the disparity means looking beyond genes to how healthcare systems operate.”

Kittles' exhausts the need for genetic research to inform personalized medicine and screening strategies tailored to high-risk populations.

Within his research, he also makes it clear in his agreement that biology alone cannot explain the full picture. Bringing us back to the point that socioeconomic status, access to care, insurance and trust in medical providers remain critical components.

This is why awareness and education are key. Webinars like UT Southwestern's Innovations in Prostate Cancer Care aim to empower Black men with information about their risk and the importance of early screening. With one of the most advanced programs for radiotherapy treatment of prostate cancer in the U.S., they hold this webinar each year to educate those who want to learn more about this disease.

A growing number of community-based organizations are beginning to partner with academic medical centers to address this crisis. These collaborations are showing early signs of progress by bringing evidence-based care directly into underserved neighborhoods. Mobile clinics, educational pop-ups and peer-led advocacy programs are offering a culturally familiar and non-intimidating path into care.

Furthermore, research funding directed specifically toward racial health equity is beginning to gain traction. This includes supporting Black researchers who often bring unique insights and community trust into their work. Many experts argue that until Black men are not only studied but also included in shaping the research, disparities will remain unresolved.

Digital storytelling is also playing a role in closing the awareness gap. Social media campaigns led by survivors and clinicians are helping to dismantle stigma and replace it with empowerment. Real-life testimonials shared through platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok have the power to shift perceptions, especially among younger generations.

Ultimately, addressing prostate cancer disparities will require an ecosystem of solutions—where policy, healthcare, education, and culture align. That means incentivizing medical schools to prioritize diversity, reforming insurance practices that create care deserts, and continuing to amplify the voices of men who’ve long been excluded from the healthcare narrative.

The prostate cancer crisis among Black men is not just a medical issue—it’s a global public health and social justice issue. From systemic racism to cultural stigmas, the road to equitable healthcare is steep but not impassable.

Support groups, community outreach and culturally competent care are making an impact. But experts agree: more must be done. This includes revising international screening guidelines, funding mobile screening units, and launching education campaigns tailored to Black communities worldwide.

In Fort Worth and beyond, the men gathered in support groups aren’t just patients. They are fathers, brothers and advocates. They are fighting not only cancer but also a system that too often overlooks them. And their voices are finally being heard.