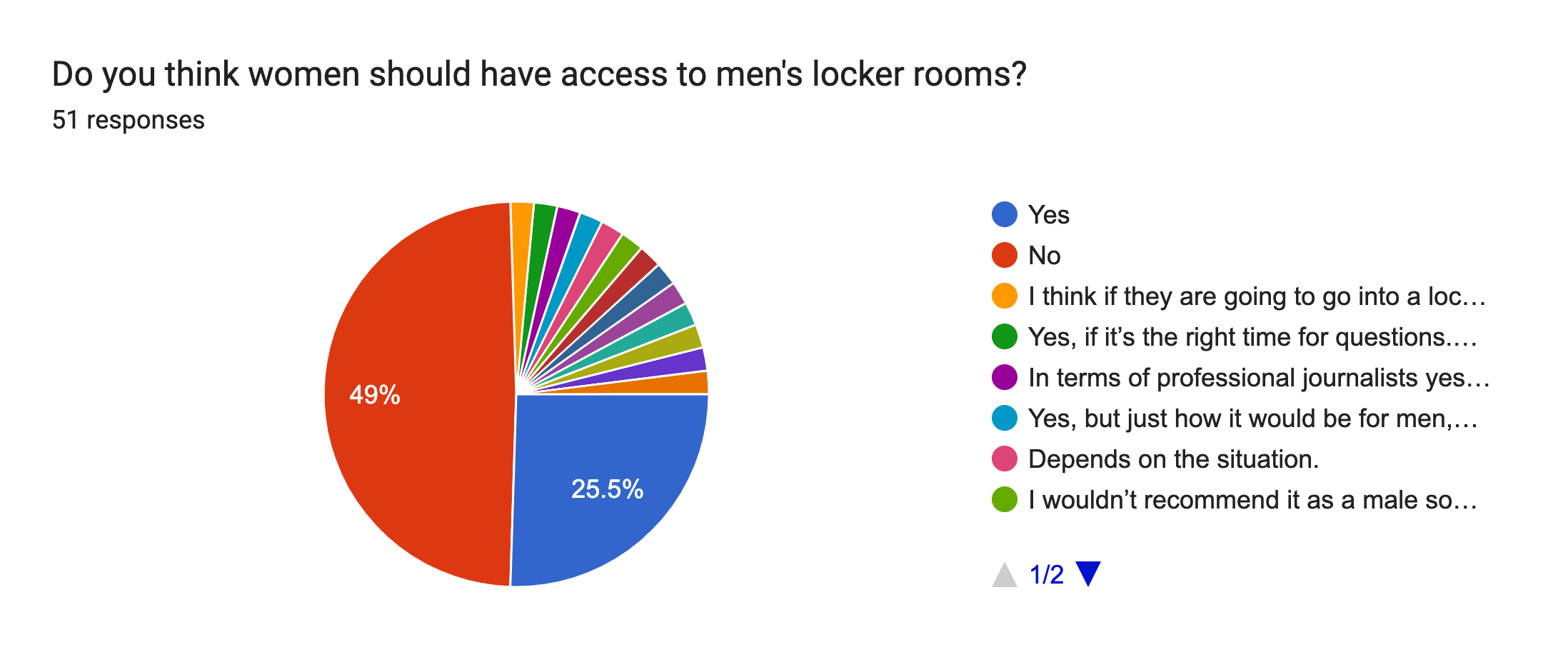

Uphill battle for women in

sports journalism

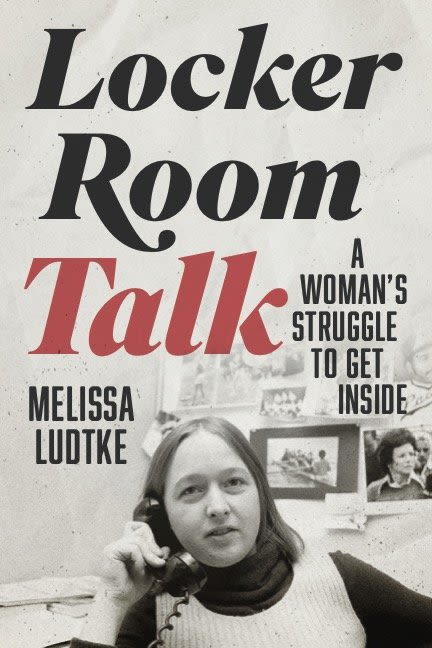

A young Melissa Ludtke photographed sitting in front of a type writer (Photo courtesy by Sports Illustrated).

A young Melissa Ludtke photographed sitting in front of a type writer (Photo courtesy by Sports Illustrated).

The journalism industry is notably competitive for both men and women, but sports journalism presents unique challenges. Women face a double standard in this male-dominated field, requiring a continuous fight to claim their seat at the table and prove their belonging in the sports space. Succeeding in this small industry remains a challenging feat, achieved by only a select few.

Women's involvement in sports journalism dates to the 1970s. In Underrepresentation of Women in Sports Journalism, Soleil Dam writes that during this era, even discussions surrounding women's participation in this space did not sit well with men, leading to women’s exclusion from crucial media meetings. Dam said that women entering team locker rooms after games for player and staff interviews was one of the initial challenges women faced as they strove to establish their presence in the field.

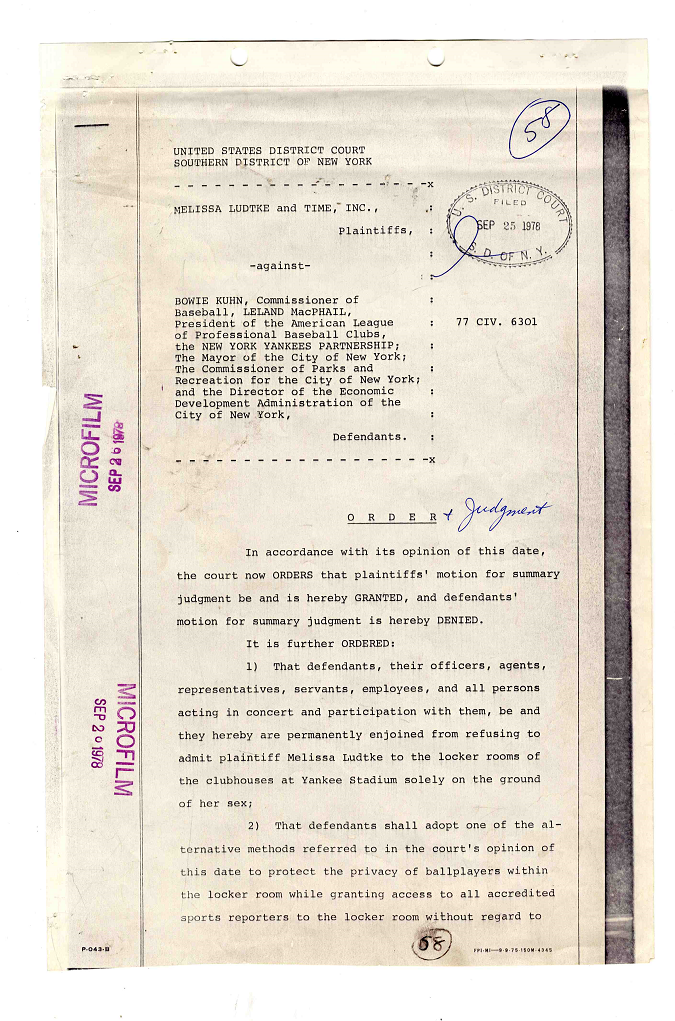

Bowie Kuhn, the former Major League Baseball commissioner, argued against allowing women in the locker rooms, citing privacy concerns for male players. However, the exclusion went beyond access to the locker room. Former Sports Illustrated reporter Melissa Ludtke was among the pioneers who challenged organizations for barring women from locker room access. With the MLB initially refusing her access, Kuhn proposed that players be brought out of the locker room to speak with her. But this left her empty-handed when promised players would not appear for interviews. Ludtke fought for access to locker rooms by suing the MLB for excluding her.

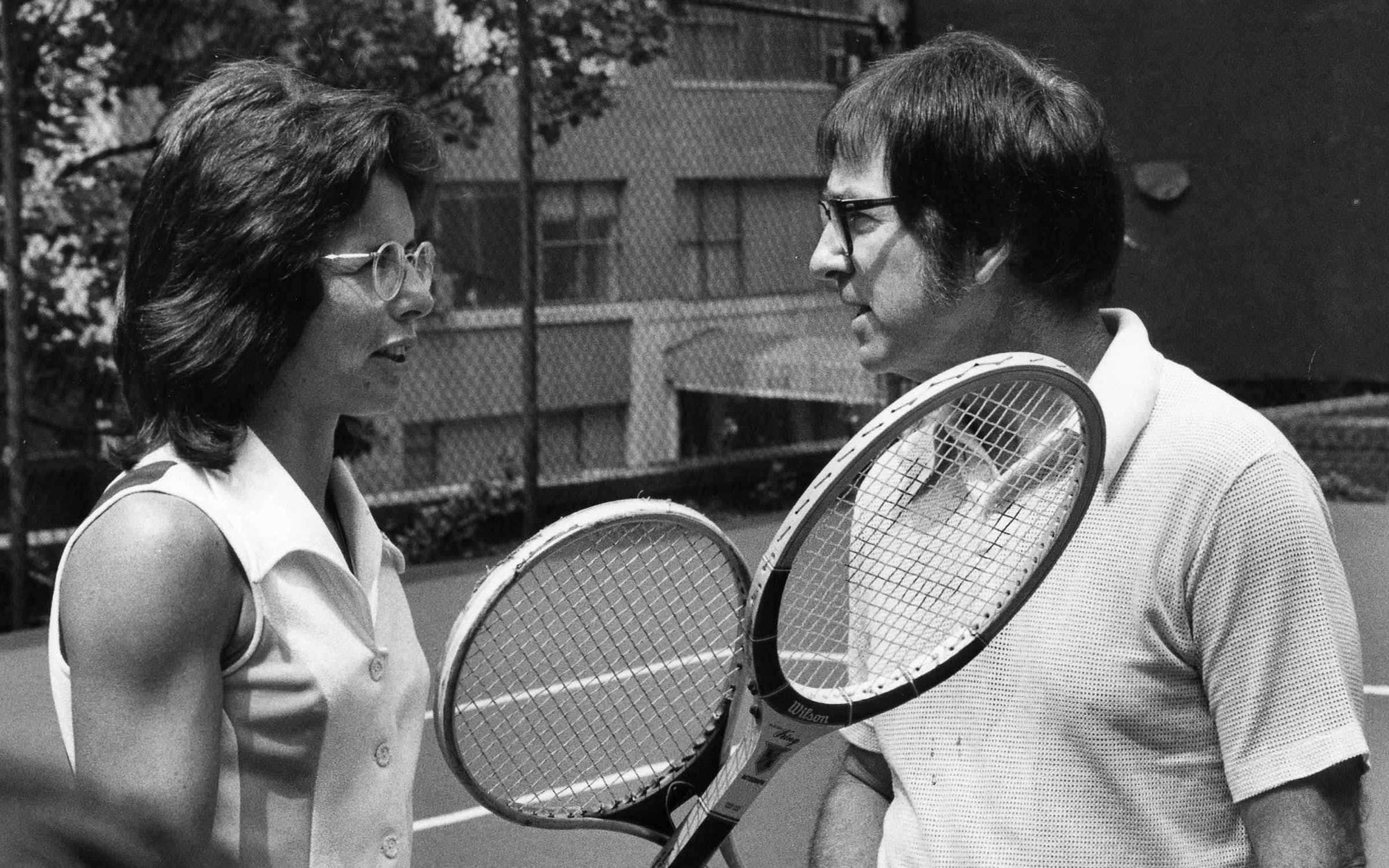

Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs at a press event for the “Battle of the Sexes (Photo Courtesy by Texas Monthly).

Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs at a press event for the “Battle of the Sexes (Photo Courtesy by Texas Monthly).

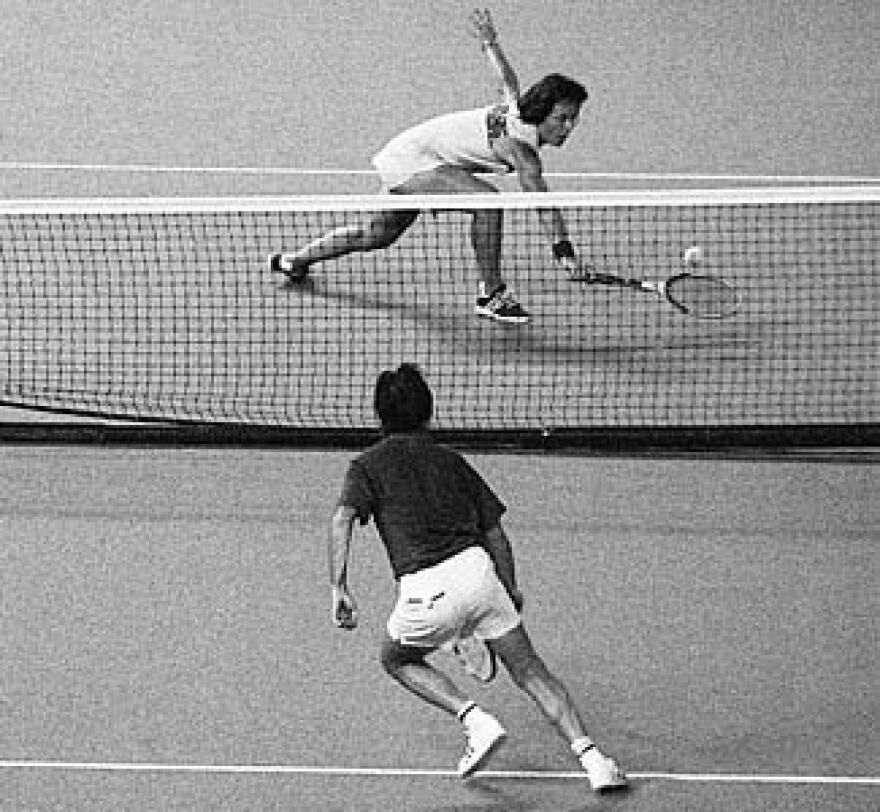

Billie Jean King playing Bobbie Riggs in the 1973 "Battle of the Sexes" (Photo Courtesy by Michigan Radio).

Billie Jean King playing Bobbie Riggs in the 1973 "Battle of the Sexes" (Photo Courtesy by Michigan Radio).

Billie Jean King win 1973 'Battle of the Sexes' tennis match (Photo Courtesy by WBALTV).

Billie Jean King win 1973 'Battle of the Sexes' tennis match (Photo Courtesy by WBALTV).

Ludtke, who had played and watched sports avidly while growing up, had just finished college when Billie Jean King defeated Bobby Riggs in the 1973 Battle of the Sexes. This event marked a turning point for Ludtke, inspiring her to pursue a career in sports. Ludtke said King beating Riggs held more significance, becoming a pivotal moment for the Women’s Movement and women in sports.

“It wasn’t just a tennis match anymore; it was a significant cultural event.”

A week after the match, Ludtke was in Manhattan, when former New York Giant Frank Gifford, who worked at ABC Sports, introduced her to the presidents and vice presidents, mostly men. There she met the only woman producer at ABC Sports, Ellie Riger, who invited Ludtke to stay in Manhattan to observe an all-women's production team working on a one-hour special, "Women in Sports", following King’s victory over Riggs and the passage of Title IX.

“When you receive an invitation like that, you do not leave town."

One day Ludtke looked up and saw Billie Jean King walking up the stairs into the studio.

“That’s it, now I know what I am doing for the rest of my life. I just knew.”

Even though Ludtke had graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and lacked any journalism qualifications, she made a firm decision to pursue a career in sports media where she had her most significant contribution. Ludtke moved to New York where she would work two jobs: one during the day as a secretary, then during evenings and weekends she worked part-time at ABC Sports, learning as much as she could, spending most of her time in the editing studios. After a long job search, Ludtke landed a job as a reporter researcher for Sports Illustrated in 1974.

Ludtke ended up having numerous stories run, but in five years she was still not promoted to a writer, “I think men had an easier time moving up than women did.”

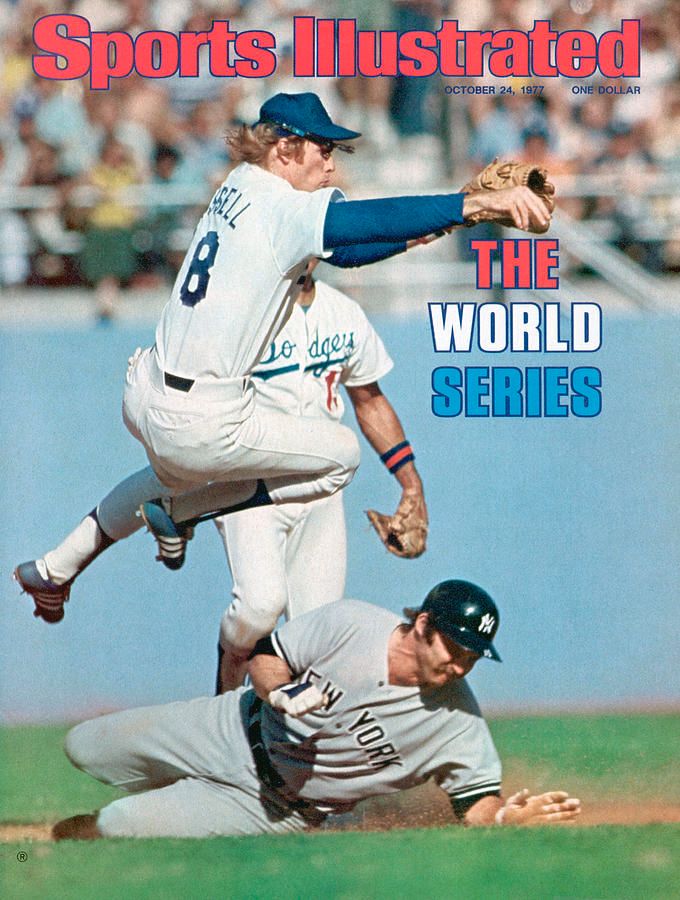

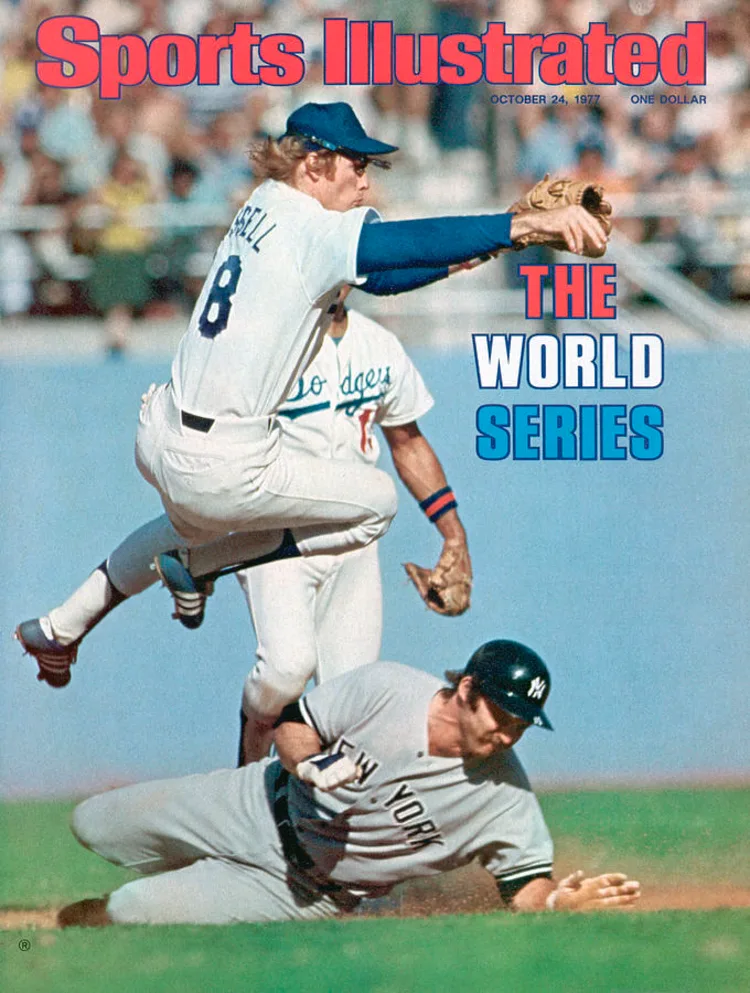

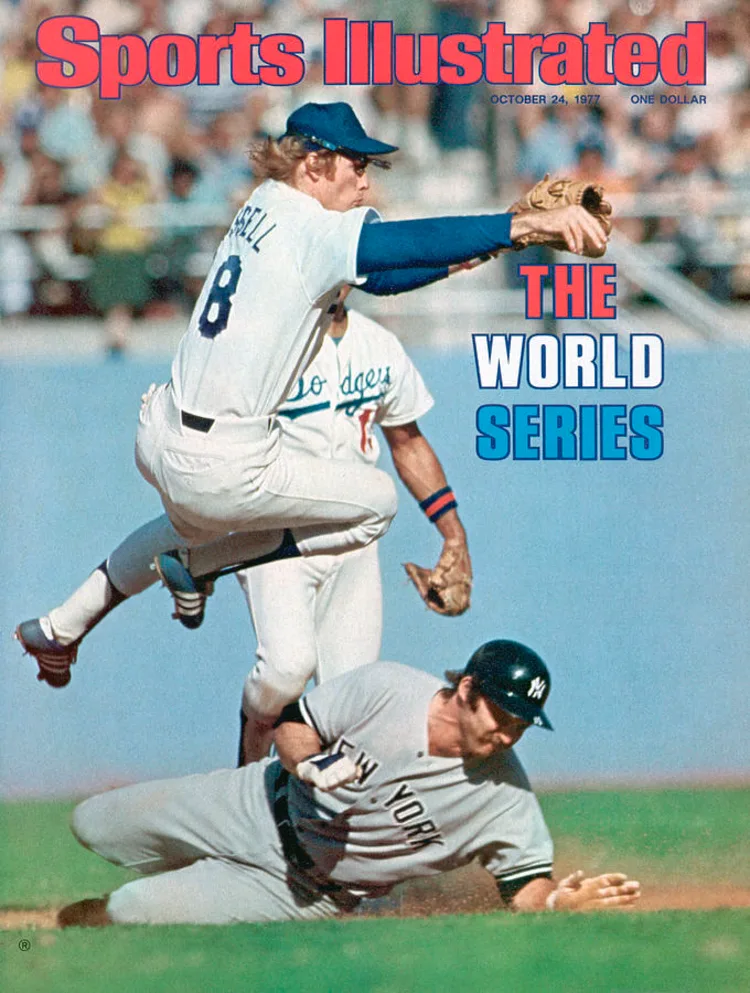

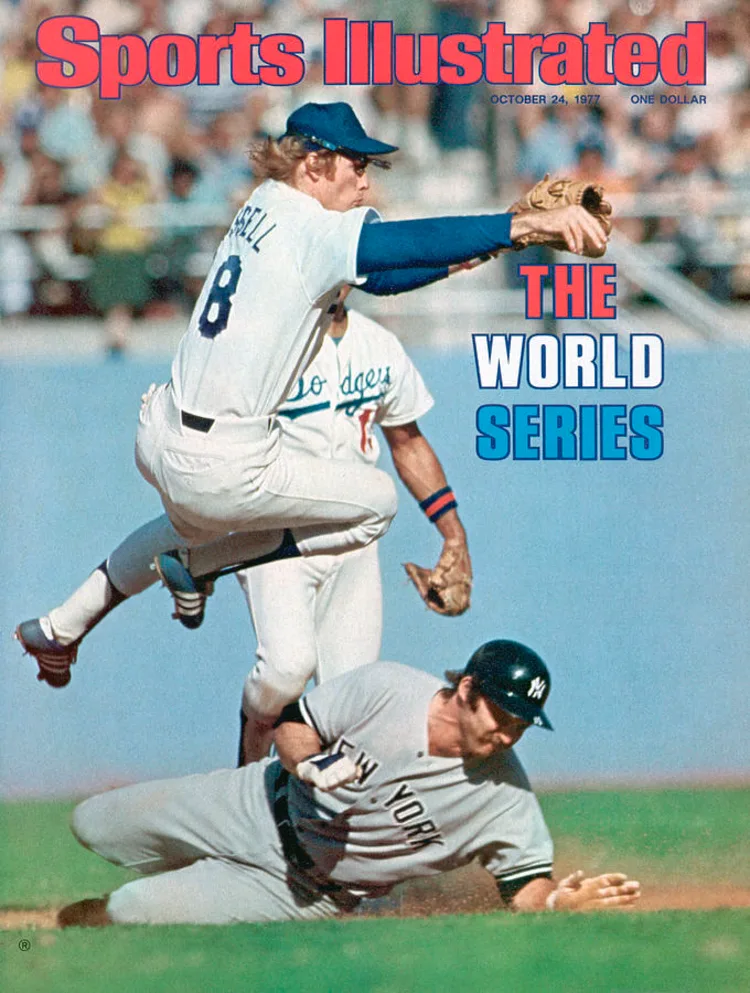

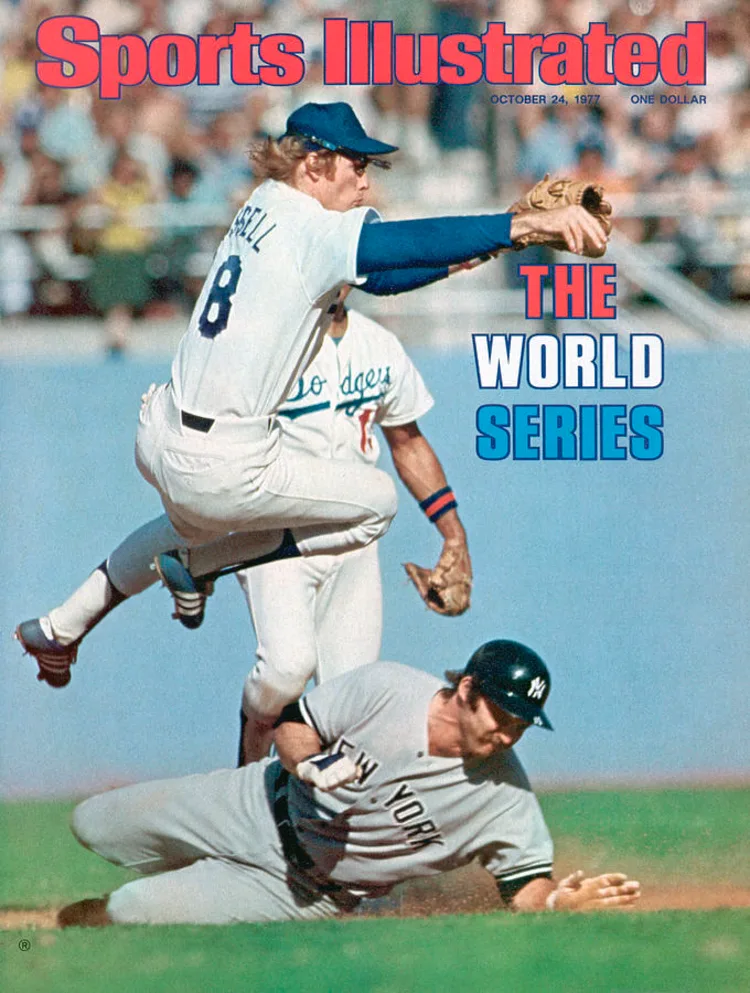

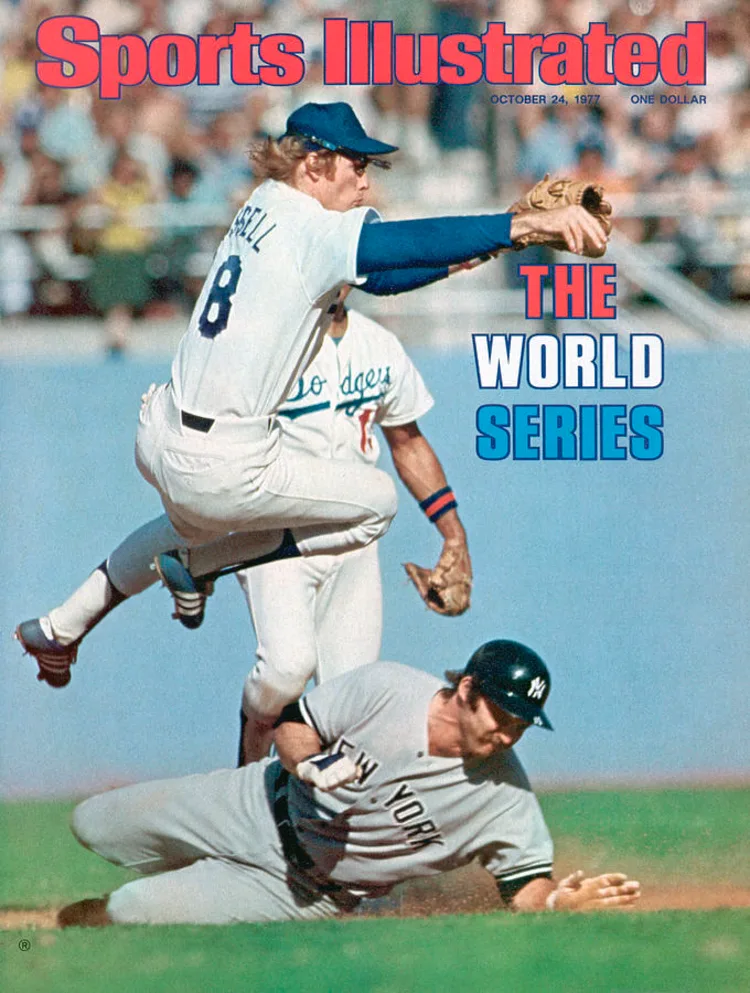

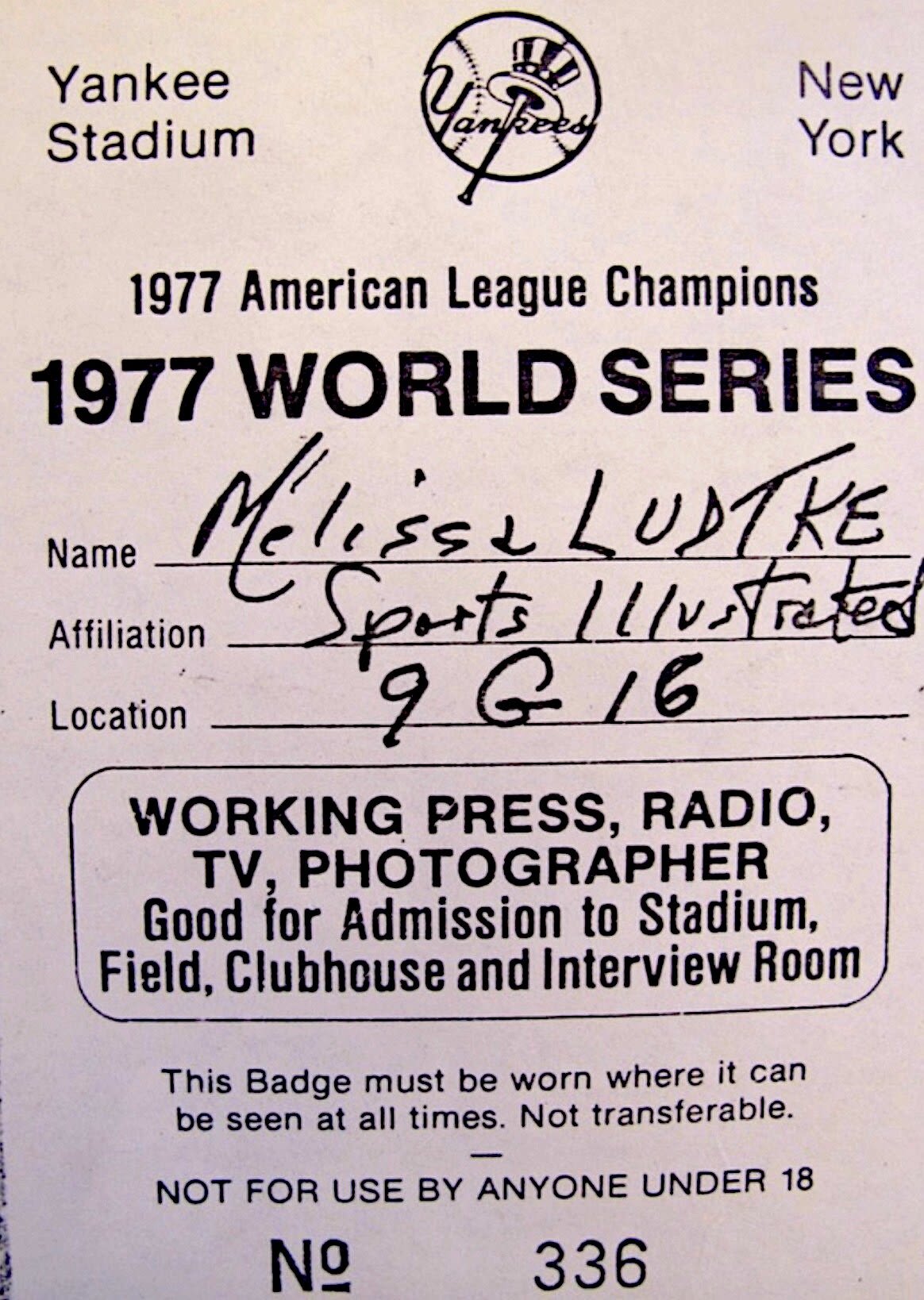

After two seasons on the baseball beat she was sent to cover the 1977 World Series between the New York Yankees versus the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Ludtke had built a relationship with the Yankees organization and received a Yankees clubhouse pass. She reported from inside the locker room and through the American League Championship. Ludtke said that through the trust she gained from the organization, she believed she would have the same access during the World Series.

“With me earning that pass after being around the Yankees, getting to know the players, earning their respect, I felt like this World Series was going to be a real opportunity to engage fully in my job. But when the Dodgers came into town I realized they had never had a woman covering them and yet I had a pass that said I could go into the club house.”

As a courtesy and out of respect, Ludtke notified the Dodgers organization that she had access to the Yankees clubhouse

Player representative Tommy John said he would have to take an organization vote for Ludtke’s access to the space. The majority of players understood that she had a job to do, granting her access.

When MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn heard the news, he decided it did not matter what the Dodgers or Yankees said, as far as Kuhn was concerned, Ludtke was not allowed into the clubhouse during the World Series or ever again. Ludtke, confused and frustrated, asked to speak to the commissioner herself but was told that it would be ‘impossible and wouldn’t be allowed.’ She said she never got the opportunity to meet him. Ludkte was able to attend the post game conference but was denied clubhouse access, forcing her to go home early without quotes for her stories.

For Ludtke, this marked the first time she encountered such barriers. When her managing editor found out, it prompted discussions about potential legal action. Kuhn offered an alternative for female journalists to interview players without entering the locker room. Ludtke viewed this as motivation to pursue legal action. “I think we know from other court cases that separate is not equal, and we wanted women to have the same experiences as men. That was the basis that drove us forward with the lawsuit,” said Ludtke.

In December 1977, Time Incorporated filed a complaint with the court to initiate legal action. The verdict was not issued until September and the court ruled in favor of Ludtke in the case. In response to the ruling, the commissioner had to put forth a media policy granting equal access to male and female reporters at Yankee Stadium, and over time, other teams provided equal access, as wellAmerican League teams were the first to do so.

In 1984, Claire Smith, then the only woman writer in the Baseball Hall of Fame, experienced discrimination when she was ejected from the San Diego Padres' clubhouse. This incident marked the last time Kuhn would get away with such discrimination. That same year, Peter Ueberroth replaced Kuhn as the MLB commissioner. His first order of business was to hold a press conference announcing that henceforth, every clubhouse in the MLB would be open equally to all reporters.

In the early stages of the case settlement, young women worldwide, many in high school or junior high, sent Ludtke letters, to which she responded.

“I remember reading those letters and hearing young girls' voices saying, ‘This matters to me, and this is something I never thought I would be able to do.’ A significant number of male journalists were upset that I had won the case and began making false assumptions about my character. Almost all were men. They sexually objectified me, asserting that I would be victimizing the men if I entered the locker rooms. Various derogatory statements were made about me, and I was portrayed unfavorably on some late-night comedy shows.” Ludtke explains she just wanted to do her job.

“I do not want to see naked men,” said Ludtke. “I am not going to see their sexual parts, that is not why I want to do this, which was the general theme of what people said of me. I just wanted to do my job.”

For Ludtke one of those ways was receiving those young women’s letters which proved to be a source of strength for Ludtke during that challenging period. She recounted a story about a woman from Westchester who had applied to be a bat girl with the Yankees. The Yankees replied with a rejection, stating that she had misunderstood the nature of the job, as it was intended for boys only. Determined to challenge this decision, the woman informed Ludtke that she planned to take the matter to the Human Rights Commission. Ludtke, recognizing the burgeoning Women’s Movement, remarked, “ I thought, wow, this is something bigger than me.” Looking back in her seventies, Ludtke finds satisfaction in realizing the historical impact of her case. “I've come to understand that it has had a lasting influence, continuing to impact the newer generation of female sports journalists.'"

Ludtke stated that it is easier to change the law than to change attitudes.

“There is no doubt that I lost in the court of public opinion. But I won in the court of law.”

She received an order from a judge who agreed that things needed to change, but it would take decades before the full impact of all the changes would take place — which, for Ludtke, is now in 2023.

“Women are now finding seats in the broadcasting booth, engaging in play-by-play and color commentary; they are not just stuck on the sidelines. However, some of the women on the sidelines do an excellent job there. We see women as sports editors, though their numbers are relatively small. Sports are tough, but there is tremendous growth among women in sports, including audiences on TV and in person.”

Records of District Courts of the United States Case: Melissa Ludtke and Time, Incorporated v. Bowie Kuhn (Photo Courtesy by Today’s Document).

Records of District Courts of the United States Case: Melissa Ludtke and Time, Incorporated v. Bowie Kuhn (Photo Courtesy by Today’s Document).

Melissa Ludtke's credential for the 1977 World Series (Photo Courtesy by Melissa Ludtke).

Melissa Ludtke's credential for the 1977 World Series (Photo Courtesy by Melissa Ludtke).

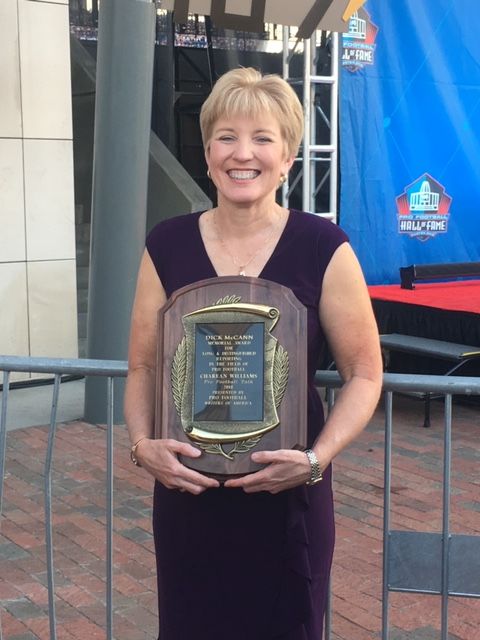

Williams shows off her lifetime achievement award plaque after the Pro Football Hall of Fame presentation (Photo Courtesy by Charean Williams).

Williams shows off her lifetime achievement award plaque after the Pro Football Hall of Fame presentation (Photo Courtesy by Charean Williams).

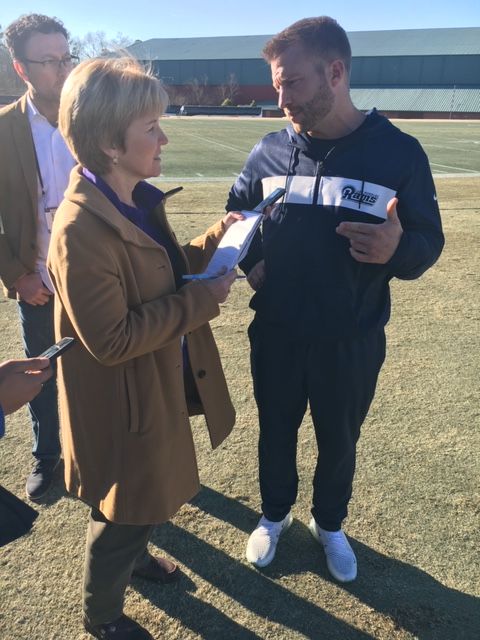

Charean Williams speaking with the Los Angeles head coach Sean McVay (Photo Courtesy by Charean Williams).

Charean Williams speaking with the Los Angeles head coach Sean McVay (Photo Courtesy by Charean Williams).

Forty years later, after many industry changes, Charean Williams had a different experience. Williams has now been covering the NFL for 25 years: covering the Dallas Cowboys for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, reporting on 24 Super Bowls and seven Olympic games, and reporting at NBC and ProFootballTalk. She is the first woman to vote into the Pro Football Hall of Fame and first woman president of the Pro Football Writers of America. In 2018 she became the first woman honored by the Pro Football Hall of Fame, winning the Dick McCann Award for lifetime achievement in NFL coverage.

Williams attributes her success back to the mentors who took her under their wing, and also the people who she did not know personally, but admired for their contributions to the industry like Melissa Ludtke.

“I am so grateful for her and others who fought that battle early on to get us in locker rooms and get us the equal access that we have now.”

Emily Jones, who covers the Texas Rangers, also appreciated Ludtke’s efforts that have enabled her career.

“By the time I got into the space it wasn’t a comfortable space to be in a clubhouse or locker room. But it is absolutely necessary for our job. Women like Ludtke who took a stand and faced a ton of criticism. I think about how awkward it was for me in the beginning so I cannot imagine her. A big thank you to her.”

From the fifth grade Jones wanted to pursue a career as a sports reporter. She immersed herself in sports broadcasting at Texas Tech University, graduating in 1988 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in broadcast journalism. Jones spent six years at KCBD-TV in Lubbock, four of which were as the Sports Director.

“I knew sports was something I always wanted to do, and at the time, there were not many women involved in sports in the early 2000s.”

Jones explained that being the sports director as a young female forced her to mature quickly.

“It made me grow up fast and thickened my skin. I was thrown into the fire; it was a sink-or-swim experience, and I tried to make it to the shore.”

Acknowledging the inherent challenges in the field, Jones emphasized that whether male or female, there will always be obstacles, but being a female in a male-dominated industry posed a few additional challenges. Yet, Jones maintained a positive outlook on these challenges.

“You could either let those challenges defeat you, or you can use them to fuel you. I chose to let them fuel me, build my character and personality. I rode it out and did not let those challenges discourage me. You have to find a way to block it out, and that is what I have done throughout my career.”

Hannah Wing reporting at a Rangers game (Photo Courtesy by All About That Base).

Hannah Wing reporting at a Rangers game (Photo Courtesy by All About That Base).

With her passion for sports, Hannah Wing, the digital host for the Texas Rangers, chose to attend one of the biggest sports colleges: the University of Southern California. Wing chose journalism as her major and said she knew she was on the right path.

Wing joined the Rangers organization in 2018. Years later after the changes made by pioneer women like Ludtke and Williams, she was welcomed into the space by women. Wing said that there were already a lot of women who worked there.

“It is a great and diverse front office. There are different types of people, genders, ethnicities. It is a great office to be a part of. I do not feel like there has been any double standard. I feel accepted.”

Williams, although happy with the progress, says that there still is not enough women involved in the industry. “I think we have made strides but there is still a long way to go. I do not notice that I stand out as much as I did when I first started out.” said Williams. “It is 2023 and we sometimes still stand out in the field we are in but I think I have become accustomed to it.”

Advice to the younger generation of female sports journalist....

"Start by doing the grunt work. Seek opportunities where you can pay your dues, immerse yourself in a learning environment, and be prepared to shoulder the responsibilities of the job."

Handwritten letters, Ludtke suggests, can make a lasting impression in a world inundated with emails, phone calls, and texts. Taking the time to send a letter shows dedication and a personal touch that is often appreciated and remembered by employers. Networking is paramount. Joining associations like the Women in Sports Media provides a platform to connect with thousands of journalists through conventions and chapters nationwide. Ludtke encourages aspiring journalists to be willing to share their advice and experiences, as this generosity tends to come back tenfold.

Williams says it is important that we pay that back to women and anybody who wants to put in the time and effort to be in this industry. She encourages this new generation of journalists but also says it is important they realize the sacrifices behind working in sports.

“You are going to be working on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years, giving up a lot of things to do this. It is a rewarding job and you are going to be able to go to a lot of places. I think at the beginning of a career, there is a lot of giving up and volunteering.”

Williams showed her eagerness to get her foot in the door when she volunteered to cover a little league. She volunteered because she wanted to prove she would do the grunt work to one day get to the NFL, where she is now.

“If I see someone doing the grunt work and proving their ability each and every day, I am more than willing to help them out. I think it is a duty for us that have been in this business for a while, to help.”

“Stay tough, build thick skin, and get ready to get rejected. Be prepared for how you will deal with it and know your stuff.”

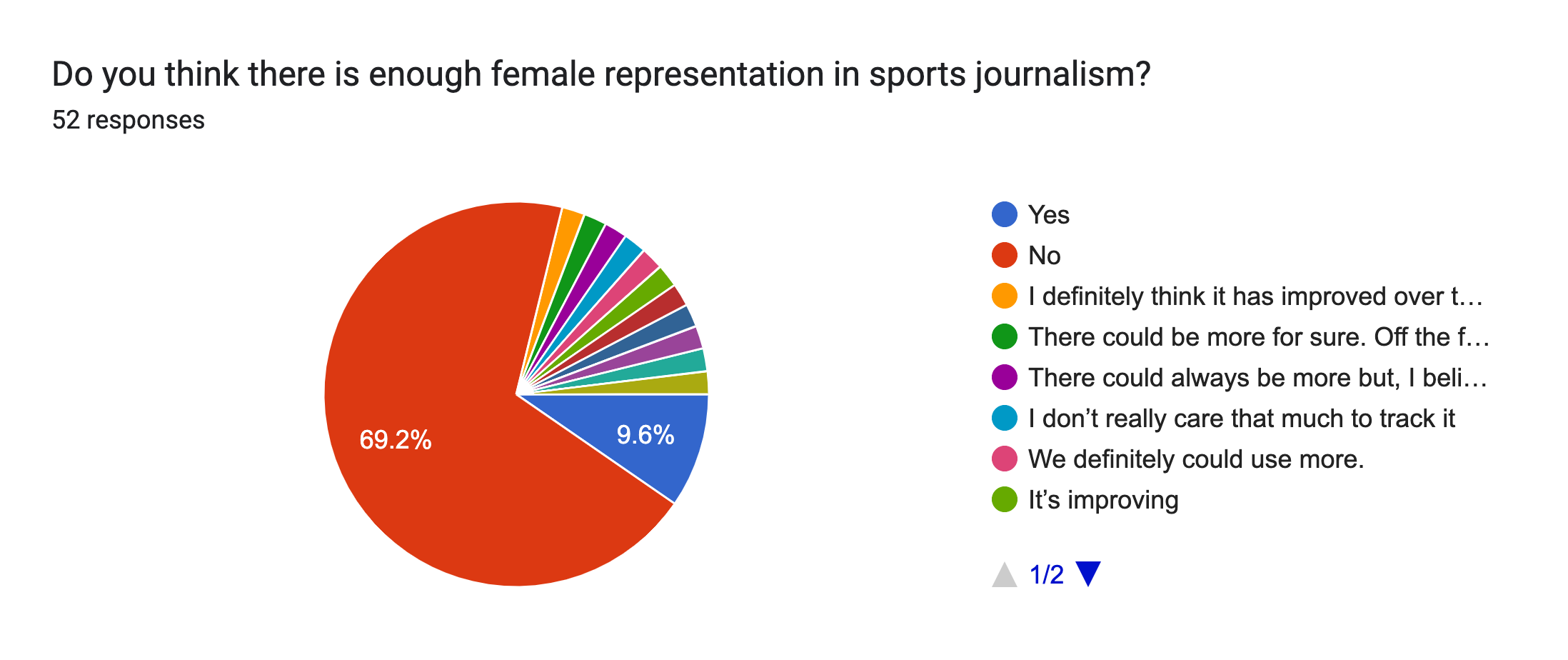

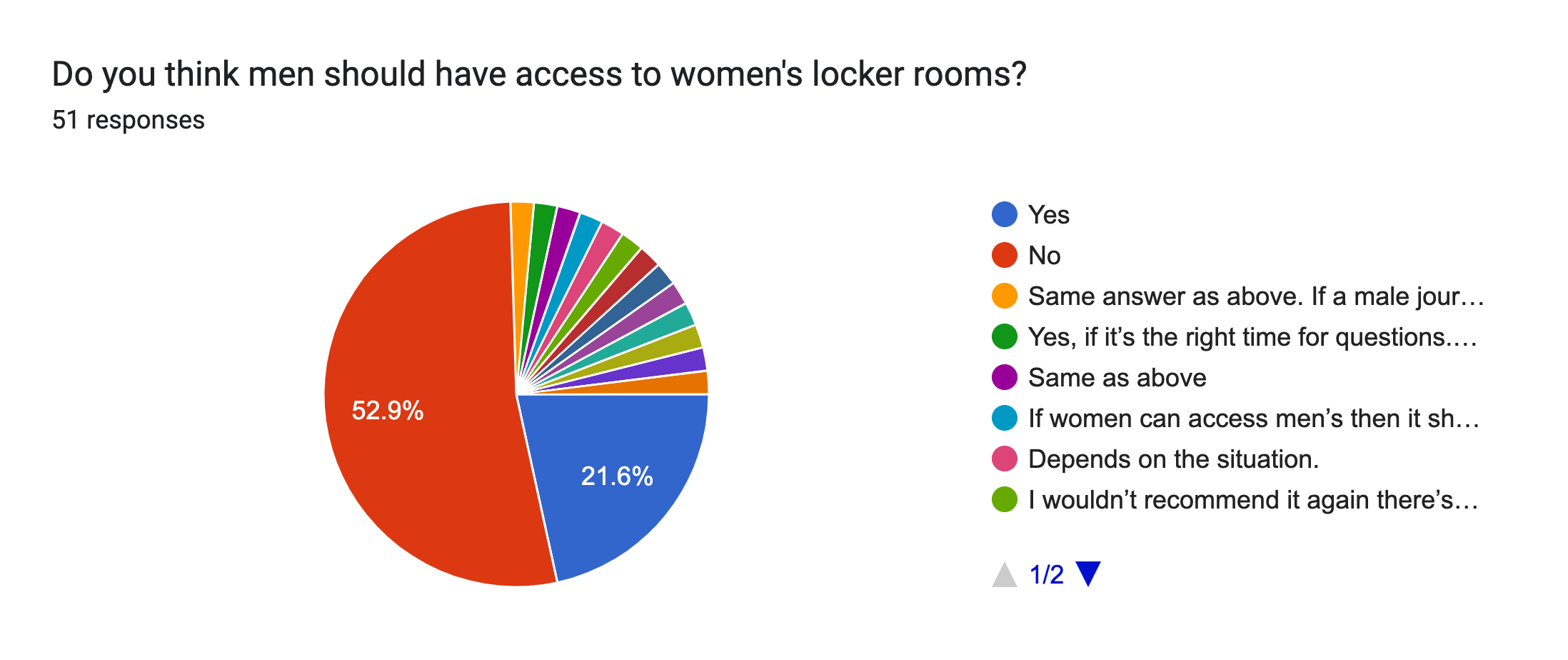

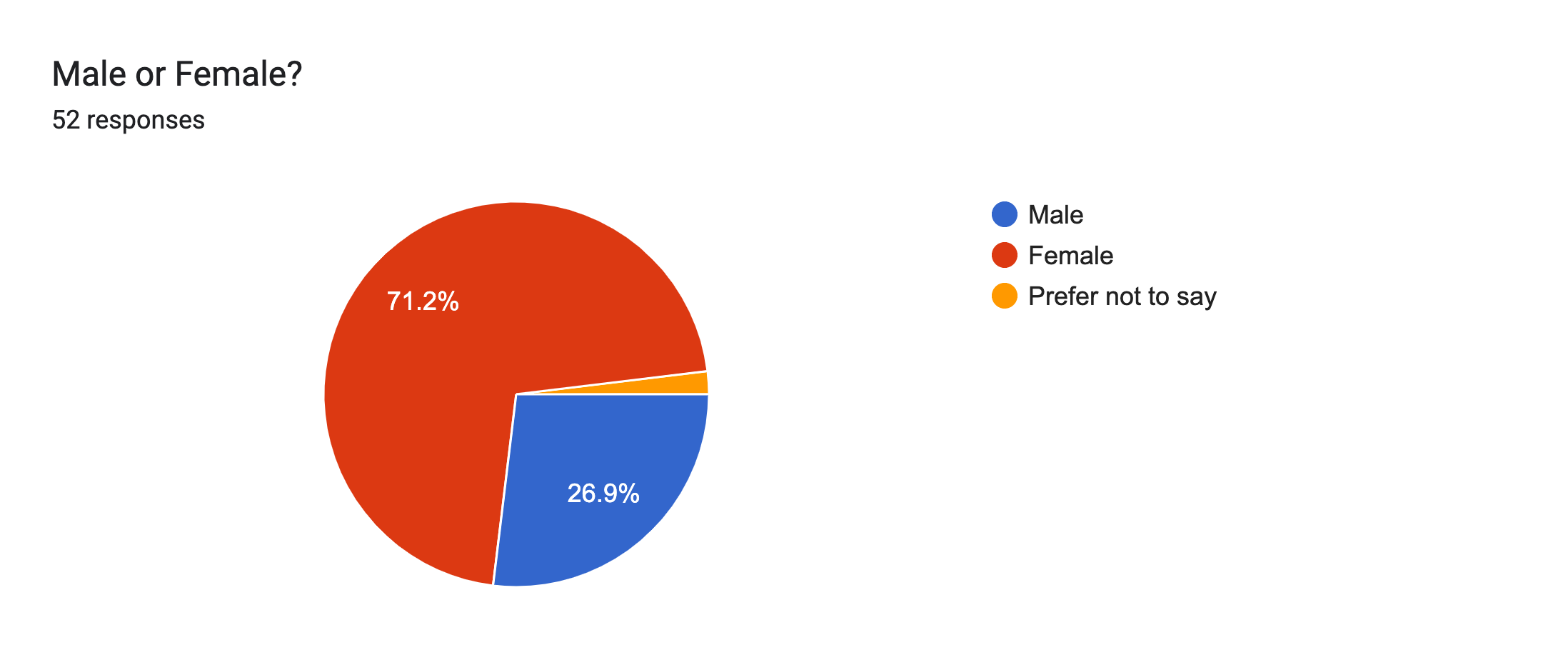

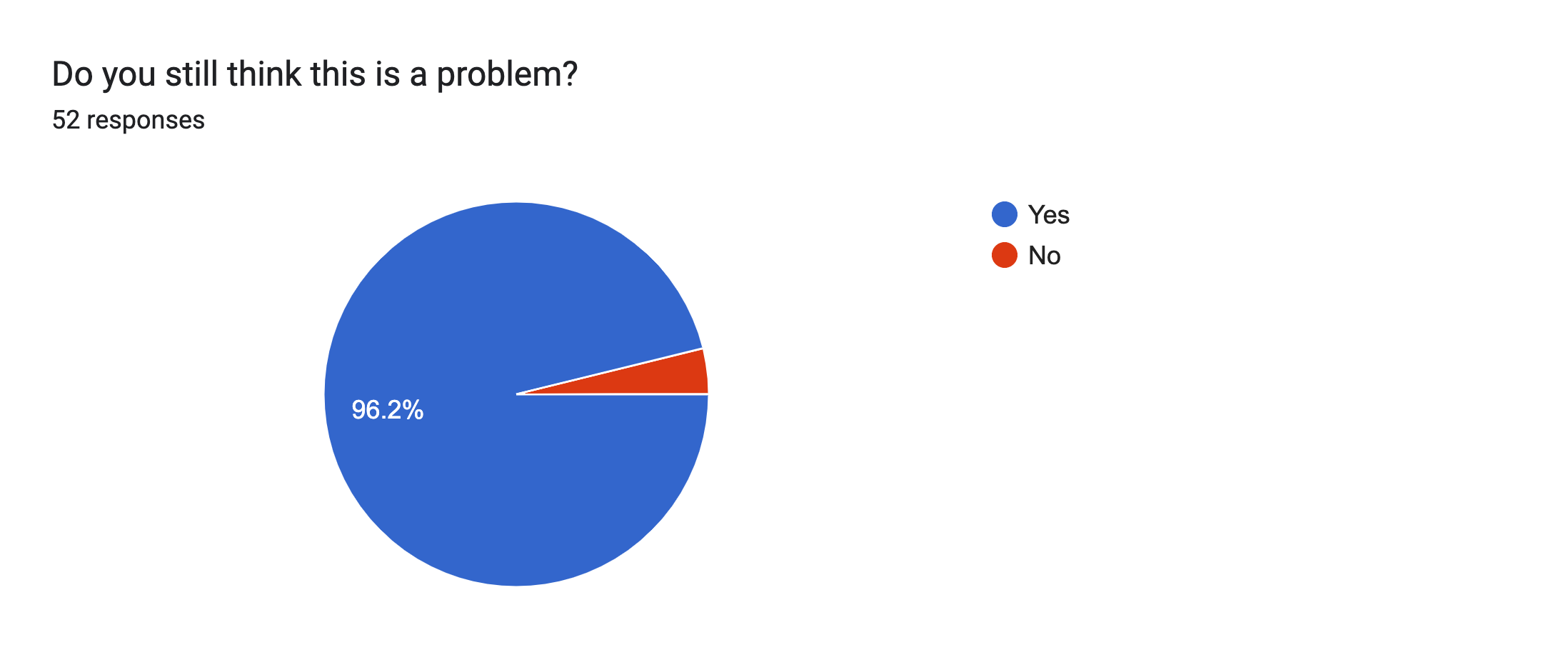

My current research indicates ongoing efforts to break down barriers for women in sports journalism, highlighting positive strides. While progress is evident, some individuals still perceive the existence of certain barriers.

Erin Andrews, the Fox Sports journalist covering the NFL, was the first person that came to mind when people were asked about women in sports journalism. ESPN's Holly Rowe and Malika Andrews were the second and third most mentioned journalists.