Three’s company: How a decade-old law failed to protect family housing near TCU

Ten years after Fort Worth limited student housing near TCU, the overlay meant to protect family neighborhoods has become another loophole for developers.

The canary in the coal mine

For thirty years, Paula Deane Traynham’s front porch in Fort Worth’s Frisco Heights looked out on tree-lined streets and rows of 1930s cottages.

She loved her 1939 home and the quiet rhythm of the neighborhood — until the sounds began to change.

Developers started buying nearby properties, tearing down single-story houses and replacing them with larger rentals marketed to TCU students.

In 2014, Traynham told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that the peace she enjoyed on her block was slipping away.

“The closer that this development comes toward my house and the more my peaceful porch is encroached on, the more I think about selling,” she said.

A year later, she and her family sold to a developer.

Since then, Frisco Heights has been extensively developed with apartments and other multi-occupancy dwellings, she said.

Traynham has described Frisco Heights as the canary in the coal mine.

“When the surrounding neighborhoods saw what was happening, they rallied their residents to actively pursue ways to save their unique character,” she said.

In 2014, Fort Worth officials introduced the TCU Residential Overlay Ordinance, a zoning measure meant to preserve the single-family character of neighborhoods near campus by limiting each home to three unrelated residents.

Even before the ordinance passed, some residents doubted the city could enforce it.

“Are they going to go door to door and ask for birth certificates?” asked Bethanne Chimbel, another Frisco Heights homeowner, in 2014. “I also wonder if it is too little too late for a lot of the areas that I have seen.”

A decade later, those warnings seem prophetic. The blocks the overlay was meant to protect are now dominated by student rentals, and the law designed to preserve single-family character has proven difficult to enforce and a big challenge to update.

Traynham’s 1930s Frisco Heights cottage. (Photo: Google Earth)

Traynham’s 1930s Frisco Heights cottage. (Photo: Google Earth)

An image of Traynham's former lot today. (Google Earth)

An image of Traynham's former lot today. (Google Earth)

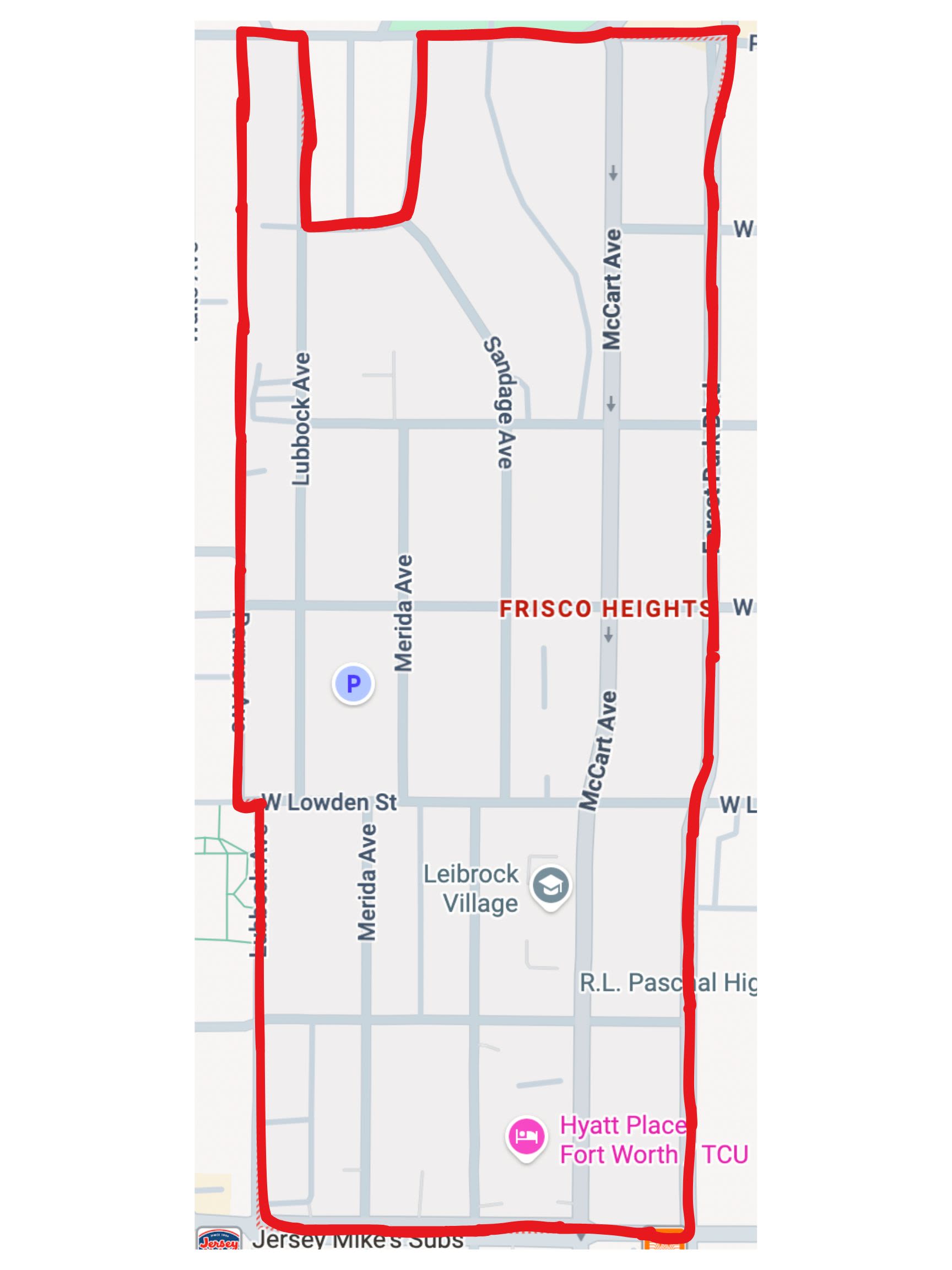

Frisco Heights

A map outlining the Frisco Heights neighborhood east of TCU's campus.

A map outlining the Frisco Heights neighborhood east of TCU's campus.

A 2015 post from the Frisco Heights Neighborhood Association Facebook Group.

Above a photo of a bulldozer clearing a lot, the caption read: “Another one bites the dust.” (Facebook)

Above a photo of a bulldozer clearing a lot, the caption read: “Another one bites the dust.” (Facebook)

Drawing the line

The TCU Residential Overlay wasn’t a ban on student housing, but rather a speed bump for development.

City planners created a special zoning district around campus called the TCU Overlay District, which limited three unrelated residents per home and added new parking requirements: two off-street spaces per house, plus one additional space for each bedroom that exceeded three.

Before that, the city’s general zoning code allowed up to five unrelated people in a single-family home.

Developers had used that rule to turn older houses into what residents called stealth dorms: large, multi-bedroom houses built for students but still technically classified as single-family. The overlay aimed to close that loophole.

Neighborhoods such as Frisco Heights, Bluebonnet Hills and Westcliff were included, areas where historic one-story homes had already started giving way to boxy, multi-floor rentals.

But from the start, the boundaries were messy.

The overlay creates one large district, but the land underneath it isn’t all zoned the same way.

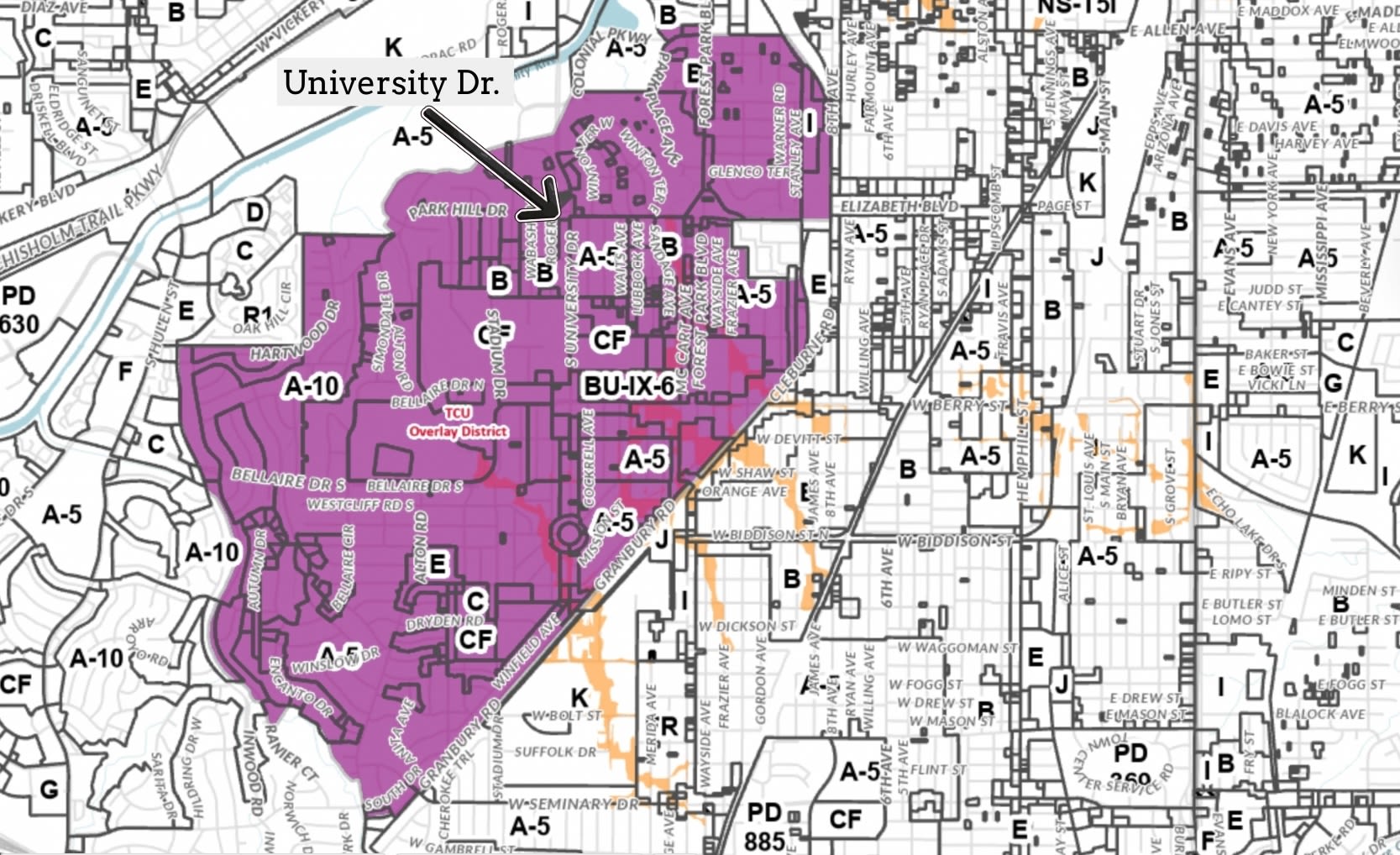

The map below shows the overlay in purple layered on top of the city’s base zoning. Areas lettered labels — A-5, A-10, B, CF — each come with different rules about what can be built.

The TCU Overlay District

The TCU Overlay Zoning District. (Source: Fort Worth Police Department)

The TCU Overlay Zoning District. (Source: Fort Worth Police Department)

Not every lot inside the overlay is breaking zoning rules. The blocks around TCU include a mix of zoning categories — everything from single-family (A-5 and A-10) to two-family (B) to various multifamily designations.

The distinction between lots is especially clear in Frisco Heights. Although the overlay added limits to single-family properties, many lots never fell under that category in the first place.

“The majority of properties in my neighborhood, Frisco Heights, were already zoned ‘B,’ meaning duplex or similar dwellings, so they were not protected from development," Traynham explained regarding the development around her former home.

The TCU Overlay regulates occupancy, not the number of units. While a single-family home in the overlay is capped at three unrelated residents, a property zoned for two-family or multifamily can contain more than one dwelling unit, each with its own maximum occupancy.

The result is a mix: two lots on the same street can be subject to completely different limits, depending on what the underlying zoning allows. It’s one reason why the overlay can feel inconsistent, and why some high-density homes are fully permitted even when they resemble the student rentals neighbors often resent.

The watchdog next door

On paper, the TCU Overlay is simple: no more than three unrelated residents in a single-family home. The enforcement piece residents feared most has proven to be the overlay’s weakest point, according to city officials and property owners.

LaShondra Stringfellow, Fort Worth’s assistant director of zoning and design review, said her department still depends almost entirely on neighbor complaints to spot violations.

“We rely on complaints from neighbors,” Stringfellow said. “We can’t just walk into a house and count beds. We need probable cause and legal access, and that can take weeks of coordination with city attorneys.”

Most reports start the same way: too many cars in the driveway, too much trash on pickup days.

According to the city’s Occupancy Investigation Form, neighbors are encouraged to document suspected violations by logging vehicle activity at an address for at least 30 days: noting license plates, times parked and overnight stays.

The City of Fort Worth's Occupancy Investigation Form.

Spotting the stealth dorms

A photo of a bedroom door with a keyed lock in a student residence.

A photo of a bedroom door with a keyed lock in a student residence.

Stringfellow said inspectors look for “telltale signs” of what residents call stealth dorms.

Extra dumpsters, keyed bedroom locks or oversized 'offices' that double as bedrooms often signal stealth dorms disguised as single-family homes.

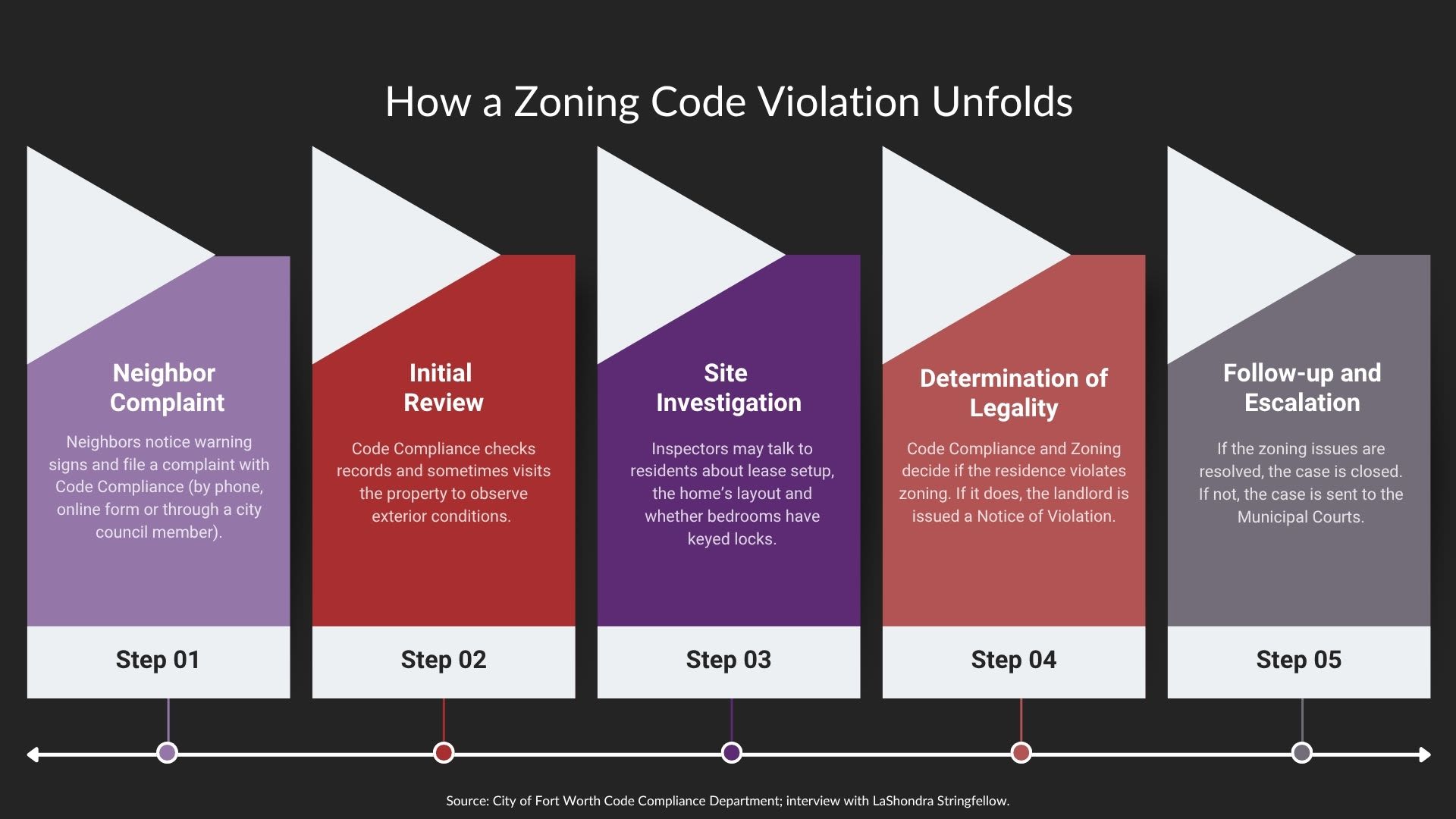

When complaints reach the city, Code Compliance reviews the case and consults Development Services when needed.

“If inspectors confirm a violation, the landlord gets a notice and up to 60 days to fix it,” Stringfellow said. “Most comply before it ever reaches court.”

But even when enforcement comes in strong, developers have found ways to adapt.

Natalie Weimer, who owns 48 student rental properties around TCU, said the overlay’s limits reshaped some developers’ construction patterns instead of stopping them.

“People are putting in homes that, according to their plans, with code, it's just a three-bedroom, but they'll have a really big third bedroom that they then split later on into two bedrooms or an office that they then put a closet in later on,” Weimer said. “So it’s created some of that underground choice that people make when they’re redeveloping.”

For TCU, whose jurisdiction ends at the campus boundary, the problem sits largely with the city.

“If there’s a zoning violation, that’s the city,” said Gregory Cox, TCU’s Executive Director for Government Relations. “If it’s off-campus noise or behavior, that’s a separate process.”

Ten years later, the web of shared responsibility has left the overlay as a law that many know, but few can enforce.

A graphic outlining the process of enforcing a zoning code violation.

A graphic outlining the process of enforcing a zoning code violation.

Some long-term developers and landlords, such as Weimer, own lots that have been grandfathered into the five-unrelated resident rule that was in place before the overlay. Landlords whose leases predated the 2014 overlay were allowed to maintain higher occupancy counts.

Yet, if they scale back, they can’t go back up.

“If you were at five before the overlay and later reduced to four, you couldn’t go back to five,” Stringfellow said.

This results in leases that are locked in at a five-resident maximum next door to newer builds that are restricted to three.

A neighborhood remade

Photos of McCart Ave. near TCU in 2010 versus 2025. (Google Earth)

Photos of Merida Ave. near TCU in 2010 versus 2025. (Google Earth)

Photos of Benbrook Dr. near TCU in 2010 versus 2025. (Google Earth)

Photos of Lubbock Ave. near TCU in 2010 versus 2025. (Google Earth)

The price of proximity

The market pressures around TCU are visible in the price tags attached to the homes within the overlay.

As redevelopment has accelerated, properties once occupied by families have become investments whose value is closely tied to their proximity to campus.

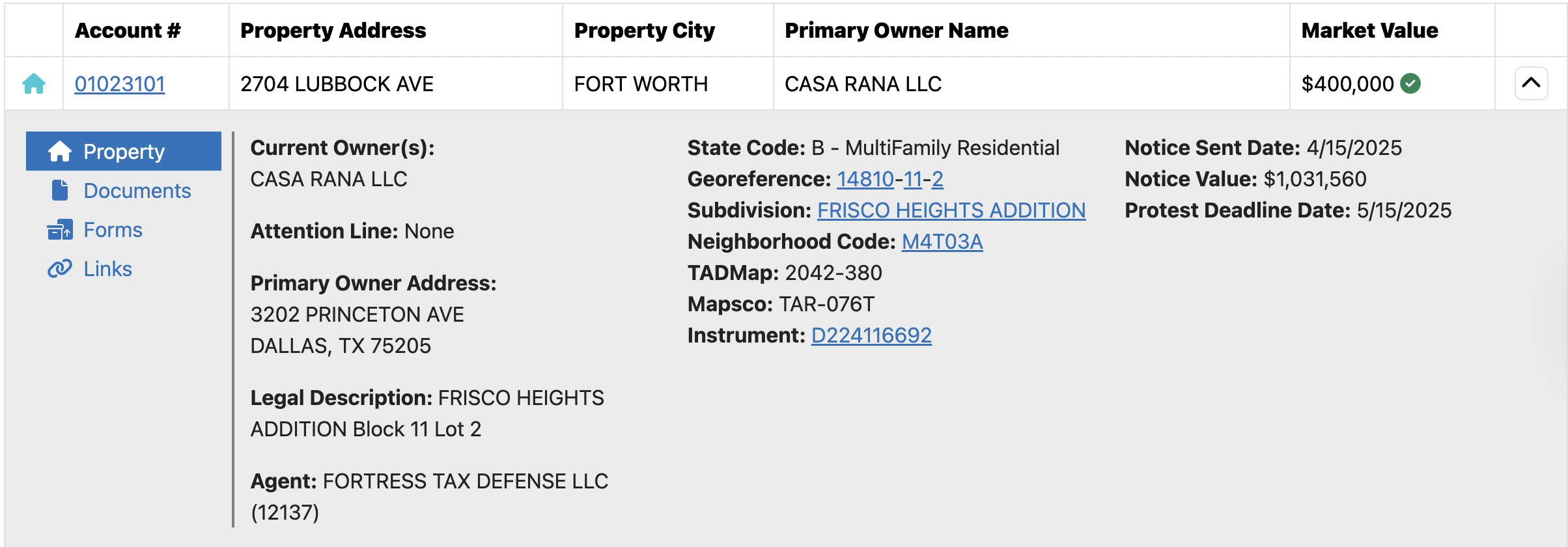

One example is 2704 Lubbock Ave, a lot in Frisco Heights zoned B – Multifamily Residential and owned by Casa Rana LLC, a Dallas-based company with multiple holdings in the neighborhoods surrounding TCU.

According to the Tarrant Appraisal District, the property carries a 2025 notice value of $1.03 million, more than double the $400,000 market value listed on the same record.

A screenshot from the Tarrant Appraisal District showing 2704's market value and notice value.

A screenshot from the Tarrant Appraisal District showing 2704's market value and notice value.

That gap reflects both rising land values and redevelopment, especially in areas where the zoning allows more density than the single-family homes the overlay was designed to protect.

The rental market tells a similar story. The duplex, with five bedrooms on each side, is listed for $7,750 per month per side and is marketed to students for its private bathrooms and walkability to campus. The price averages roughly $1,550 per bedroom.

For residents like Traynham, who sold to a developer in 2015, the economics became impossible to ignore. “There are only a very few owner-occupied properties left in Frisco Heights,” she said.

The $1 million valuations, investor owners and per-bedroom rents make clear that proximity to TCU has become its own currency. Even with the overlay’s occupancy limits, the underlying land values and the zoning that permits higher-density development continue to push the neighborhood in a direction the original ordinance was never equipped to stop.

A campus of the future

Even with years of steady redevelopment, some property owners say the pace may be slowing.

Landlords are watching the university’s next steps before making additional investments, especially as TCU outlines future projects through its evolving Campus Master Plan, Weimer said.

“There’s a limited amount of real estate around TCU, and so I actually don’t think there will be that much more redevelopment,” Weimer said. “We’ve kind of gotten to a saturated point… everybody will probably be pausing for a year or two to see kind of what happens with TCU, see how demand kind of falls out, and then probably make decisions going forward.”

TCU’s master planning documents focus on improvements within the campus footprint; new academic buildings, residence hall renovations, student spaces and facility upgrades. Changes in enrollment, housing capacity or on-campus development affect the demand for nearby off-campus housing.

Weimer added that any shifts in demand “will likely affect people that are located further from TCU,” suggesting that properties closest to campus, the ones most sought after, may remain the most insulated.

A decade later

For Traynham, the story began on a quiet street lined with 1930s cottages. A decade later, the porch is gone, many of her neighbors have moved and Frisco Heights looks little like the block she once knew.

The overlay that promised protection slowed the redevelopment but never reversed it; overshadowed by rising values, investor ownership and the steady pull of a growing university.

As TCU updates its campus plans and landlords watch what comes next, the question facing these neighborhoods is no longer whether they will change, but whether any of their character will survive.