The silence of violence: missing and murdered Indigenous women portrayals in the media

ABOUT MMIW

Native and Indigenous women are not safe. Whether on tribal lands or in urban communities, they live with the risk of violence.

They are 1.2 times more likely than non-Hispanic White-only women to experience violence in their lifetime.

More than four out of five Native American women have experienced violence in their lifetime, according to a 2016 study from the National Institute of Justice.

But it’s the missing White women who make headlines, the evening news and viral social media posts. These women are often introduced to the public through idealized lenses: dedicated mothers, devoted wives and beloved daughters, sisters and friends.

This frame became so common when compared to the coverage of missing women of other races and ethnicities, that the late journalist Gwen Ifill, a Black woman, described it as Missing White Woman Syndrome. This observation has often been noted as a reason why victims from other racial identities receive less media coverage. This isn’t entirely unique to Native women: according to the Black and Missing Foundation, 40 percent of missing cases are people of color.

In 2012, the hashtag #MMIW, or Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women was coined by Sheila North Wilson, who was later elected as Grand Chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) in Sept. 2015. She wanted to bring attention to the staggering number of American Indian/Native American and Indigenous women who are sexually assaulted, abducted and murdered.

MAKING NOISE:

Olivia Gray, founder of Northeastern Oklahoma Indigenous Safety and Education

In response to the MMIW crisis, Native and Indigenous leaders have established advocacy groups and organizations across the country to offer resources to victims, families and community members. Olivia Gray founded NOISE: Northeastern Oklahoma Indigenous Safety and Education, an MMIW advocacy group that responds to unmet needs in northeastern Oklahoma.

“I like that acronym because I think we need to make noise,” said Gray, a member of the Osage Nation. “I think it’s okay if people are uncomfortable because people don’t change as long as they’re comfortable. And we need to change a lot of things.”

Gray said NOISE takes a holistic approach, helping victims and families while also connecting with communities for educational purposes.

“We can’t meet every need, but what we can do is make them aware of resources that are out there,” she said. “Educating the Native community is important, because if you’re a Native woman, I feel like we all need to learn some foundational stuff about how to be an advocate because we are in so much danger.”

Experiences of violence are elevated in both urban settings and tribal reservations. Gray’s tribe is one of the 14 federally recognized Native American nations in the U.S. Attorney’s office in the Northern District of Oklahoma. Having served her tribe as the director of the Osage Nation Family Violence Prevention Department, Gray was already doing advocacy work when she answered the call to help MMIW victims.

“In 2018, a Native man from over in the Miami area called me and said ‘Hey, there’s a missing person. They’ve asked me to help and I don’t know what I’m doing. Can you help me?’ and I was like, ‘Yeah. I can help.’ I didn’t know about a missing person or how to do that either, but I knew other things,” Gray said.

That phone call turned into a call to action. Shortly after that conversation, NOISE was formed in 2019. From arranging for dog searches to filing protective orders, Gray and her team do a little bit of everything by offering guidance and support through the myriad of challenges that victims and their families often face alone. As an advocate, she hasn’t been afraid to speak up for Native women.

“I get prosecutors that get mad at me. And judges. And police officers,” Gray said. “But I’m not here for them. I’m here for victims. I am supposed to be biased for that victim.”

Gray and others are often the voices of the MMIW crisis. NOISE has used its digital platform to raise awareness of missing people because both local and national media often overlook Native people in their reporting.

“Every now and then, we can get somebody to pick up a story, but that is usually a huge surprise,” Gray said. “Most of the time, we will send stuff out and we know it is not going to go anywhere.”

Recent studies have shown that media outlets have often failed to include MMIW coverage in their reporting. The Urban Indian Health Institute examined 506 murdered or missing Indigenous women cases. It found local or national news media covered only one-quarter of the total number of cases (about 934 articles), according to a recent study. Continued coverage is even more rare, as less than one-fifth (14%) of those cases were covered more than one time and less than one-tenth (7%) were covered more than three times.

NOISE has begun sharing missing persons fliers on social media. Gray said the group’s Facebook posts typically reach about 34,000 people.

“I don't want whoever has that person to be able to open their phone without seeing that flyer,” Gray said.

Researchers suggest that traditional news media don’t see endangered Indigenous women as relevant to news audiences. Stereotypes, ideologies and systemic forces impact personal perceptions of news producers that determine newsworthiness and gauge potential interest of audiences, according to an article written by Kristen Gilchrist that was published in the peer reviewed journal, Feminist Media Studies.

But for Gray, the reason behind the lack of reporting is clear: “No one cares about Native women enough,” she said.

VISUALLY DRIVEN:

Melissa Greene-Blye, journalist

As an experienced broadcast journalist and enrolled citizen of the Miami Nation, Melissa Greene-Blye often found herself explaining her positionality.

“It’s almost like I had to learn,” said Greene-Blye, who now serves as an assistant professor at the University of Kansas School of Journalism. “I had to start asking myself the question, ‘Am I an Indigenous person who happens to be a journalist, or am I a journalist who happens to be Indigenous?’ It took me a really long time to understand it is both.”

Native American representation in the newsroom is fractional. In 2019, Columbia Journalism Review reported that Native Americans make up less than .05 percent of journalists at leading newspapers and online publications.

“When you look at employment statistics across the country in the news industry, we are very under-represented and we always have been,” she said.

Greene-Blye said she was often viewed as the sole voice for Native issues: “If a story at all touched on Native-anything, suddenly, I would become the ‘go-to’ person. Honestly, I didn’t mind that, because I knew I would do a better job on that from that perspective.”

Of the many issues Indigenous communities have faced with the media, Native people have deeply experienced the lack of MMIW news coverage. The issue is alarming for Native and Indigenous people. According the MMIW Urban Indian Health report, which examined over 500 MMIW cases, more than 95 percent of cases in their study never received national or international media coverage.

Greene-Blye said that ultimately, issues of misrepresentation are an issue of sourcing.

“When we see these cases that garner a lot of national attention — particularly in my field, which is a visually-driven field — it’s because the visuals are out there,” she said.

Gabby Petito, the 22 year old woman whose body was found in a national park in Wyoming, is an example of disproportionate visual media attention.

A search for “Gabby Petito” in the Nexi Uni media database yields more than 2,900 results between Sept. 1 when her parents reported her missing and Sept. 23 when an arrest was issued in connection with her death.

Many criticized the media for its staggering coverage of Petito while overlooking victims of color.

According to a podcast from WNYC News, between 2011 and 2020, over 700 Indigenous people went missing in the state of Wyoming. (85% of them are children, and 57% are women.) While the media closely followed Petito’s case, there is little known about the Indigenous women who went missing in the same state.

The differences in coverage may stem from the media’s implicit or explicit communication that stories of nonwhite victims do not hold the same value as the experiences of White victims, according to a study by Zach Sommers in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology.

Greene-Blye said this type of indifference and neglect has fostered suspicions and distrust among Native and Indigenous people when it comes to news media.

Greene-Blye said instead of favoring cases of missing people, the media should consider how to level the playing field and create standard criteria for stories.

“When someone goes missing, that person matters to a family, to a community,” she said.

Most of all, she said the industry should ask one question: “Why is this missing person a lead story and this one's not a story at all?”

“We have so often seen this ‘parachute’ journalism: jump in, cover how terrible things are on the ‘rez,’ how bad or dangerous the ‘rez’ is, and then back out,” Greene-Blye said. “There is no context. There is no long term follow-up.”

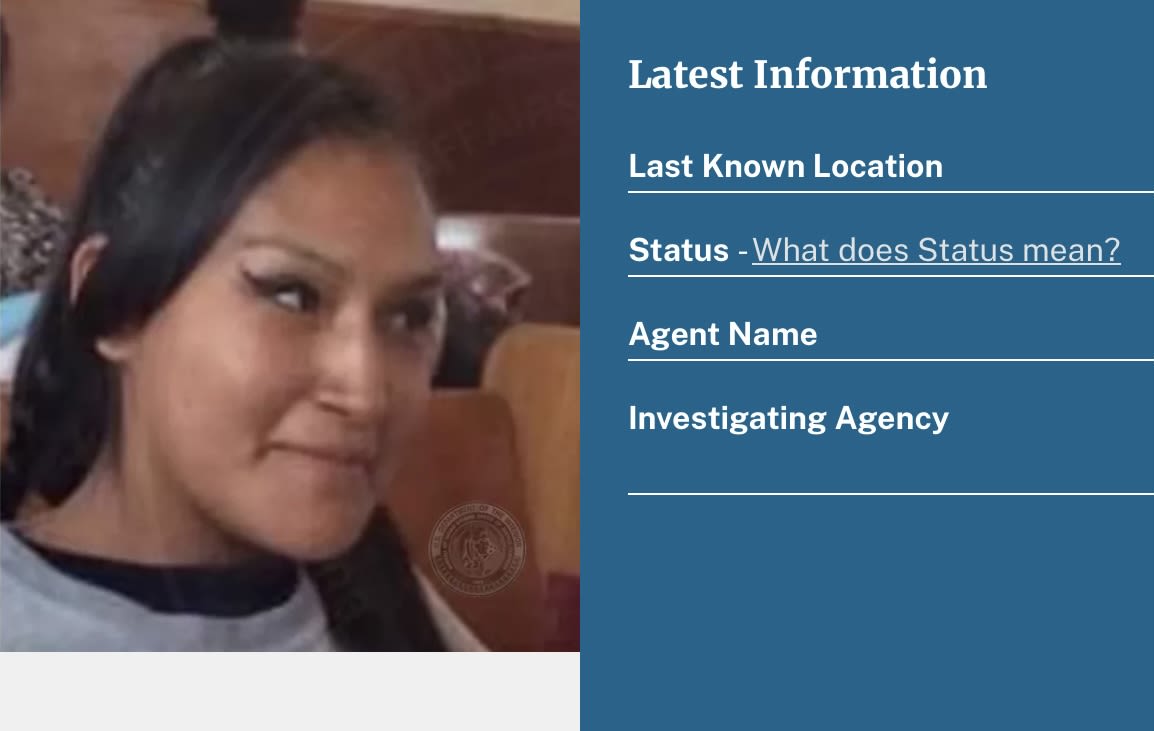

IDA BEARD IS MISSING:

Law enforcement and the media

Ida Beard, 29, was a Cheyenne and Arapaho citizen who went for a walk in El Reno, Oklahoma where she lived with her blind mother and four children.

She never returned from visiting friends. But two weeks went by before police accepted a missing persons report; the case didn’t garner media attention.

Five years after she went missing, Oklahoma passed Ida's Law, which requires the OSBI to obtain federal funding for a liaison position and create a database for MMIW cases. Dale Fine was selected to serve in this new role as special agent for the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation.

Fine, an enrolled Cherokee Nation citizen, said most people are not familiar with government investigations.

“They may see some things on TV, but actually, when it gets down to experience, we may have to explain to them what the whole process is and why it takes so long,” he said.

The lack of media coverage is compounded by concerns that law enforcement is also indifferent to the fate of these women and girls. Oklahoma has the largest population of people who are “American Indian alone,” according to the Census Bureau.

The experience for families is heavy, especially when they are left without answers about what happened to their loved one.

“They are dealing with a very – if not the most – traumatic moment in their life,” Fine said. “It’s just very tragic what the family is having to go through.”

Fine works with MMIW cases in his role with the OSBI. His early career began in law enforcement with the Cherokee Nation marshal service. He began his journey with the OSBI in 2012 in the special crimes unit, investigating everything from homicide, to officer-involved shootings, suspicious deaths and missing persons cases.

As the OSBI liaison, Fine met with victims’ families, grassroots organizations, and nonprofit MMIW chapters to assist with these cases.

“I got to hear a lot of feedback from victims’ families, which was very insightful and they were knowledgeable about the issues they were having with their missing loved ones,” Fine said. “When you start looking at tribal members and tribal communities and relationships with law enforcement, as it was described to me, there was some historical distrust.”

In a 2018 report from the Urban Indian Health Institute, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls in 2016, but only 116 cases were logged in NamUs, the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database.

“Basically, you have missing persons across the nation, and then you have identified persons or remains that have been found,” said Fine. “What this is trying to do is cross reference them.

Fine said that time works against the family and the officer: “We highly encourage doing that full report. Get that information. Get specific details on that information and get that out on our radio system with the media and say ‘Hey, this person is missing’ and what they are wearing.”

“If you do this report and get all this information, and two hours later maybe your missing person or even runaway juvenile shows up back home, and you feel like you did all this work and here they come walking back. You know, that’s okay. That’s a good ending to it,” Fine said. “That’s what you want.”

Fine said families have expressed their feelings about the lack of communication.

“If they have a missing loved one and they are not having that communication with law enforcement, they feel like law enforcement may not care,” he said.

For the communication work of his department, Fine said the media is a partner and asset in their efforts.

“We understand that their reach is very wide and a lot of people will listen or tune in, whatever the organization may be,” Fine said. “If we need to get the information out there, I know that we can contact the media to put it out there.”

“Just listen to them. Listen to victims’ families. Listen to their concerns. Listen to some of the issues that they have. Knowing that someone out there cares and is listening to them really goes a long ways, too.”

A WESTERNIZED WAY:

Examining stereotypes and culture

For Kate Fox, timing is everything in the MMIW crisis.

“We consume news so quickly. We want a story, and we want it now. We want it to be within 10 seconds, and then we want to move on,” said Fox, a professor at Arizona State University’s school of criminology and criminal justice. “That's just not going to give a complete, accurate story of families and survivors.”

Fox founded the Research on Violent Victimization (ROVV) Lab at ASU to promote safer and healthier communities and to hopefully reduce Native and Indigenous victimization. She received grant funding to hire Native and Indigenous people full-time to collect data of Native and Indigenous individuals who have experience with losing a loved one.

Fox said Native and Indigenous people guide and shape everything in the ROVV lab.

“Research can be very harmful, if not done with cultural sensitivity, being trauma informed and also serving a purpose for the peoples who the research is really form,” Fox said.

Historically, this informed approach has not been utilized in the media coverage of Native and Indigenous people, including MMIW cases.

“We operate in the United States in a Westernized way of doing things,” Fox said. “Reporters are given very short time frames for writing their reports, sometimes like a day. What ends up happening is – to no fault of their own — the reporter is at the mercy of the system that requires them to produce what they believe to be a comprehensive report in a matter of a day, maybe it's a week, maybe it's a month. Whatever it is, it does not always operate on the timeline of being inclusive and respectful of Indigenous peoples.”

Gilchrist’s research in Feminist Media Studies supports Fox’s observations, focusing on how stereotypes that portray Native women as unclean and accessible for sexual exploitation shape Indigenous experiences.

Fox has observed that stereotypes and fault are often linked: “Not only are they victimized once, or in the case of domestic violence, over and over and over, by the actual crime, but also they are victimized in so many other ways by feelings of that this was their fault, which it was not.”

In her work with Native and Indigenous communities, Fox said she recognizes the issues that Native and Indigenous people experience in trusting the media.

“A reporter cold calls or cold emails, or sends a message through social media or knocks on the door of an Indigenous person, and there could be, in many cases, some questions that the Indigenous person has: ‘Who are you?’ ‘What kind of stories have you written before?’ ‘How have you treated families and survivors before?’” Fox said.

While these trust issues may stem from historical misrepresentations, contemporary media disseminations continue to overlook Native and Indigenous voices.

For example, researchers Dr. Danielle Slakoff and Destiny Duran examined 34 episodes of popular true crime podcasts that featured a stand-alone missing woman/girl's case; nearly 80 percent of the episodes featured a White victim. There were no episodes about a missing Indigenous woman.

Social media has been a game changer for MMIW advocacy, creating shifts in how this information is consumed and produced, but there are still limitations. While social media allows advocates to bypass the traditional media, its reach is often limited to Native and Indigenous communities, said Sheena Gilbert, a social science research analyst in tribal crime, justice, and victimization at the University of Nebraska-Omaha.

Gilbert, citizen of the Stockbridge Munsee tribe, said the larger society has to recognize the MMIW crisis extends beyond Native and Indigenous people.

“A missing person is not just a Native issue,” she said. “It is an everybody issue. A human being has gone missing. We need to find them.”

Fox said news coverage should be elevated because MMIW cases are life and death situations.

“When a Native American person goes missing, or is murdered, they shouldn't be on page 45 in the newspaper with a tiny little blurb,” Fox said. “That needs to be front page news. What we've been finding for years is it hasn't been fair. It hasn’t been fair at all.”