My Trauma Isn't Transactional

Examining the relationship between Black students and the essays they wrote for college

During the fall semester of my high school senior year, I sent off 15 college applications. 15 times my name slid across a desk, to be judged through the lens of potential success.

Most of my application was identical for each submission: same transcripts, same scores, same letters of recommendation.

But the essay was something that changed every time, and not because I was submitting different prompts.

I mulled over the options trying to pick a topic that would highlight my writing and still pack a punch. I wanted an essay that would get passed around the office or featured on one of those college tip blogs.

But nothing in my life seemed profound enough.

So, I wrote about failing a class. And my mom losing her job for a couple months. Things that, while true, had little influence on my life, and grossly misrepresented my actual experiences.

I sent it nonetheless. But it wasn’t until I was on the other side of the whole process that I could truly reflect on the decisions I’d made.

By that time, I had become an intern with TCU’s Office of Admissions, where I frequently interacted with prospective students. I reviewed applicant portals and made notes on their profiles, and before long, began to pick up on a pattern: there were extreme differences between the personal statements. For the exact same prompt, there were stories of struggle and stories of success. It fascinated me how the same question could have opposite answers – especially since the stories of hardship were especially traumatic.

Themes of broken families, poverty, and illnesses; and almost always they traced back to a Black applicant.

college essays are so embarrassing like.... Imagine pouring your heart out on a letter about your struggles and trauma just to get rejected lmao

— Manny (@manny_oe) September 22, 2022

I came to understand what happened my senior year – I had fallen victim to an unspoken expectation that plagues Black students seeking higher education.

Black students experience a unique form of trauma that is solely based on their racial identity. And while Black people are not monolithic, they may be predisposed to certain, specific, shared experiences. These experiences can be pervasive, affecting everyday experiences, perceptions of the world, and access to resources.

The culmination of the three offers a different perspective that is often exploited by college admissions practices. Black students are encouraged, if not incentivized by financial assistance, to repackage their trauma as “grit,” “hard work,” or “perseverance.”

Not only is this an unfair metric by which to evaluate applicants; but it risks reinforcing existing inequities, which can be internalized by the storyteller themselves.

But the application essay did not start out nearly as complicated.

The admissions process as we know it today was developed over a century ago. By the early 1900s, some schools had already adopted entrance examinations that required standardized tests and essay responses. Some students even sat for interviews while others submitted letters of recommendation.

It’s hard to conceptualize a student through data alone, so these submissions can serve to enhance applicant profiles. The original goal was to give a writing sample that was strong, clear and concise. But since an essay can act as supplementary information, it has grown in prominence over time.

According to College Board, one of the oldest, not-for-profit college access organizations, essays have become one of the most nerve-wracking parts of an application.

“The essay is an opportunity for students to personalize their college application,” says College Board. “They can show their commitment to learning and their eagerness to contribute to the community.”

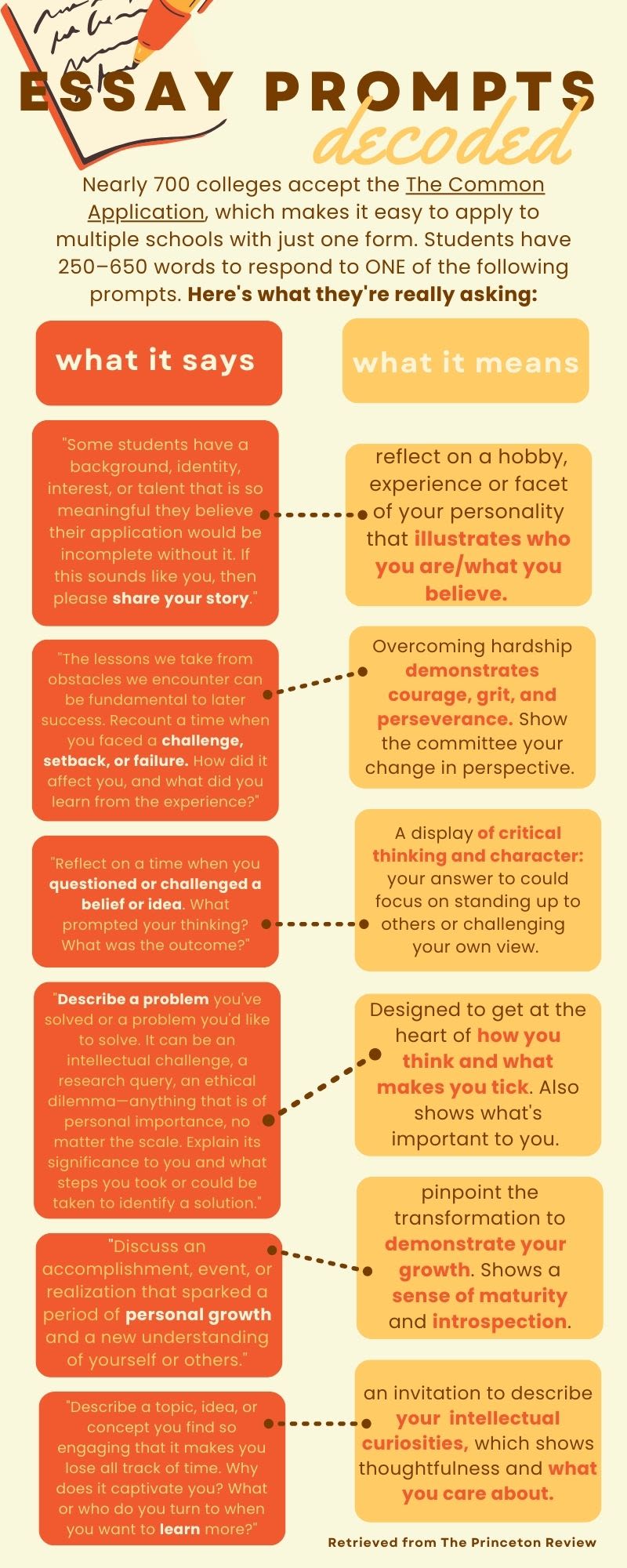

Application essays are open-ended, which means there is no frame of reference for students to write. It is their job to interpret the prompt, so their essay’s content is entirely subjective.

It is for this reason that students began to lean on the advice of their selected institutions. It was admissions counselors who originally set the precedent of “standing out” through the personal statements.

In an admissions blog from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the author compares two potential introductions for an admissions essay. The first one reads:

"I'm honored to apply for the Master of Library Science program at the University of Okoboji. For as long as I can remember, I've had a love affair with books. Since I was 11, I've wanted to be a librarian."

The second one reads:

"When I was 11, my great aunt Gretchen passed away and left me something that changed my life: a library of about 5000 books. Some of my best days were spent arranging and reading her books. Since then, I've wanted to become a librarian."

The author concludes that the second introduction is much more impactful, and would leave a better impression on the admission team. But this preference perpetuates the theme of adversity, which has even greater implications for marginalized groups.

Championing trauma as a determinant of grit can misrepresent one’s self-identity and how they are perceived. They may internalize their struggle and think they have no merit beyond their survival. The personal statements exploit their adversity - but what is the exchange?

There is a growing discourse around race in admissions, and the role it plays in promoting diversity. There are two cases currently in the Supreme Court that directly address affirmative action. In both cases, Students For Fair Admissions (SFFA) allege that admissions policies at selective universities discriminate against Asian-American and white applicants.

Aya T. Waller, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Michigan, is a pioneer in this field of research. Her dissertation examines the growing discourse about college admission essays, which suggests that most Black students write about their personal struggles or traumatic experiences. In her research, Waller has found that Black undergraduate students expressed a keen awareness of this expectation. More importantly, Waller reveals that this expectation is a racialized one, shaped by social factors, like counselors and teachers.

Black students may already feel “othered” when entering the college admission process; Waller’s study suggested these students carry messages that link their experiences as Black people to racial discrimination, tropes, and stereotypes.

“I was told, ‘You’re smart and you’re from the hood, you’re from the projects, colleges will love you.’” Elijah Megginson, then a high school senior, wrote in a piece published in the New York Times. He went on to write that he and other Black students that planned to apply to predominantly white institutions (PWI), felt like they were put in a box for the clichéd story of a Black kid in America–a token of diversity at a university compelled to prove their inclusion of a statistically insignificant portion of their student body.

It reminds me of another TED Talk from Nigerian novelist, Chimamanda Adichie, about the dangers of the “single story.” The single story represents the idea that when only one perspective or narrative is presented, we draw overly simplistic and incomplete understandings of people, places, and situations. So, when Black students feel compelled in their writing to play into a stereotype or expectation, they are further perpetuating the labels they wish would dissipate.

Racism attempts to reduce Black students to a single story and how labels are imposed upon the stories they share in their college essays.

When applying to college, Black students are often told that what makes them different will make them stand out. But I theorize that an emphasis on these “differences” have put Black students in a box that they’ll spend the rest of college trying to climb out of.

My research aims to identify a link between the personal statements students write and their relationship with the school itself.

Methodology

In order to maintain control of one of my research variables, I decided to look at students from the same university. I did not want the type of institution, size or location to influence the subjects differently. TCU provided a great case setting to conduct all of my research.

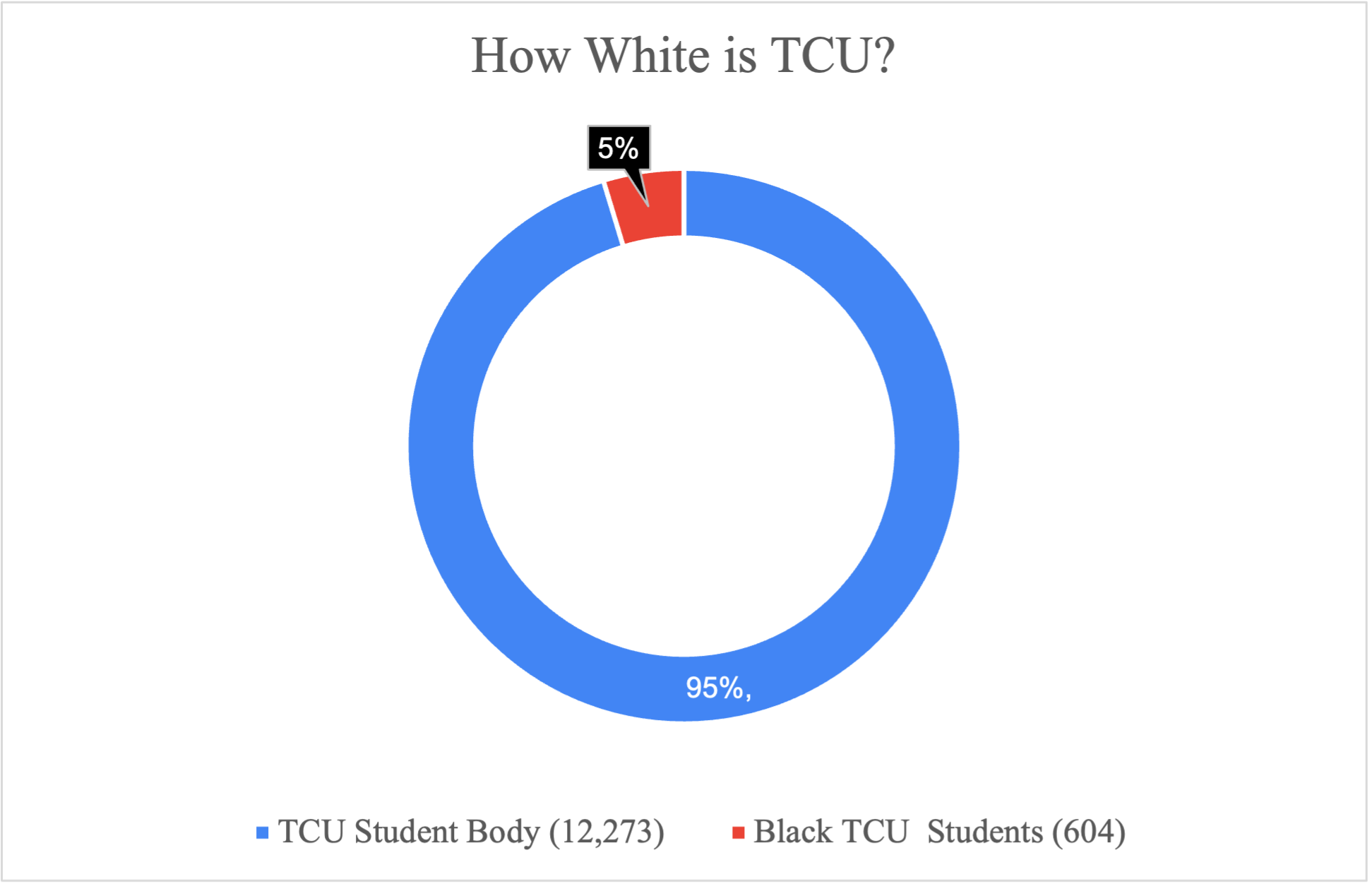

During the fall 2022 semester, there were 604 students who identified as Black enrolled in classes at TCU. This represents 4.9% of the student population, which is a little less than a percentile from the record-high 5.8%, set back in 2015.

This is important to establish the makeup of campus, to provide context to the student’s responses. These students are historically and objectively underrepresented, which will undoubtedly show in my qualitative data.

This study will examine two different groups – Academic scholarship holders and non-scholarship Black students at TCU. The university has three full-ride scholarship cohorts: the STEM, Community and Chancellor Scholarships; all of which are designed to increase the representation of high-achieving but underserved students.

I wanted representation from each of these cohorts, and I wanted my data to cover at least 10% of the Black student population. This equates to roughly 60 students.

I knew coordinating 60 interviews would be a tough feat; but since I also wanted to quantify the scope of students affected, I opted for a mixed method approach. I found that a combination of surveys and interviews would heed the most comprehensive results. It would help me identify a trend and then support the explanation with a why.

I sent two separate surveys to students over a two-month time frame. From these surveys, I was able to select a sample of students to conduct a more in-depth, follow-up interview.

I also located two incoming TCU students, who are currently high school seniors at a local Fort Worth high school. I figured their essays would be fresh in their minds.

Since Waller’s research suggested that social actors influence essay topics, I also reached out to their high school counselors. I spoke with admission counselors at TCU, who reviewed their profiles and read their essays. I also spoke with the director of education and training for the College App, the leading application platform for undergraduate admissions. I wanted to analyze their different prompts to discern what was really being asked of students. I have a theory that Black students lean towards certain prompts that they think will tell a “struggle story” best. In analysis of the prompts, this would be the challenge essay, or the essay about solving a problem.

Results & Discussion

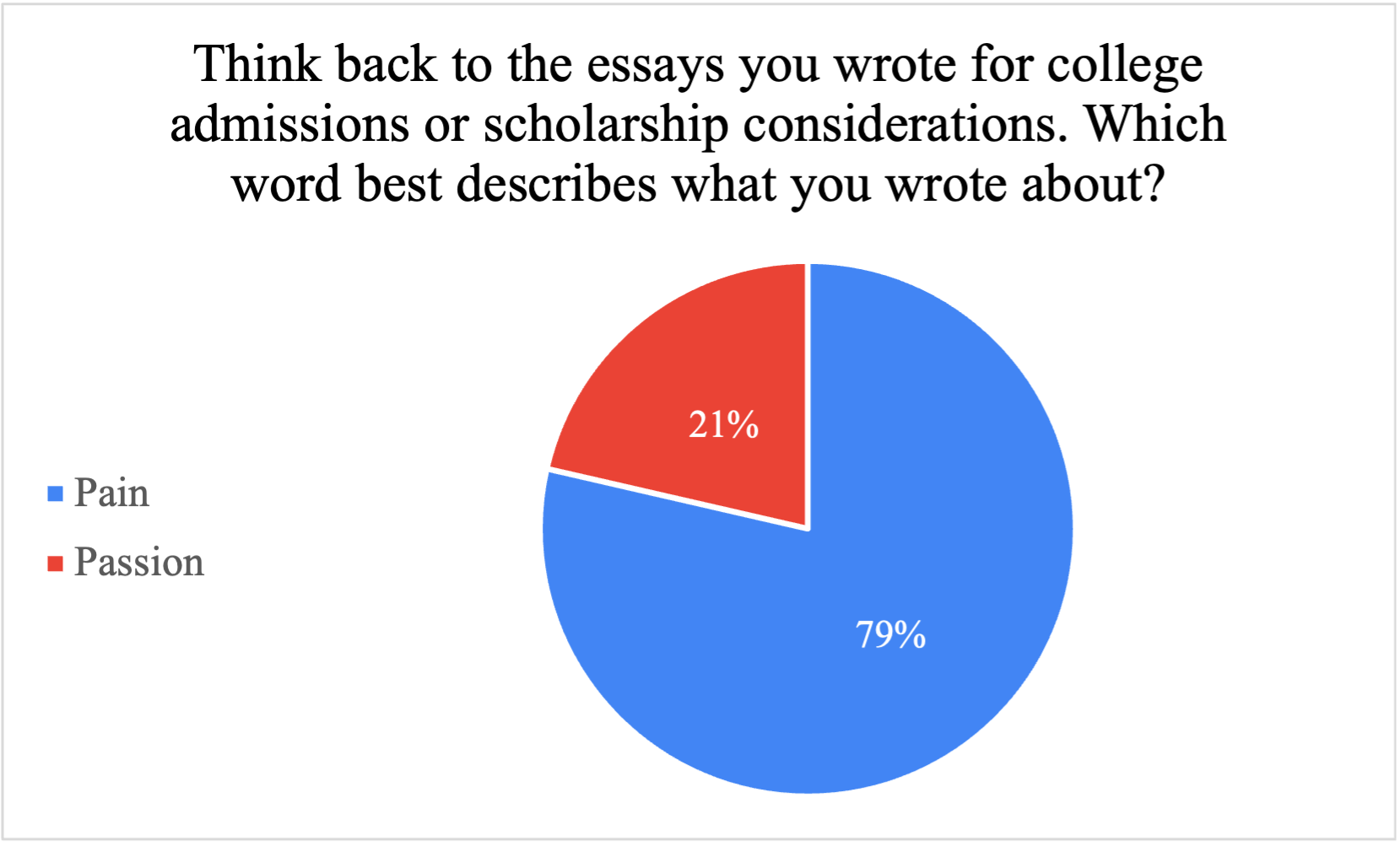

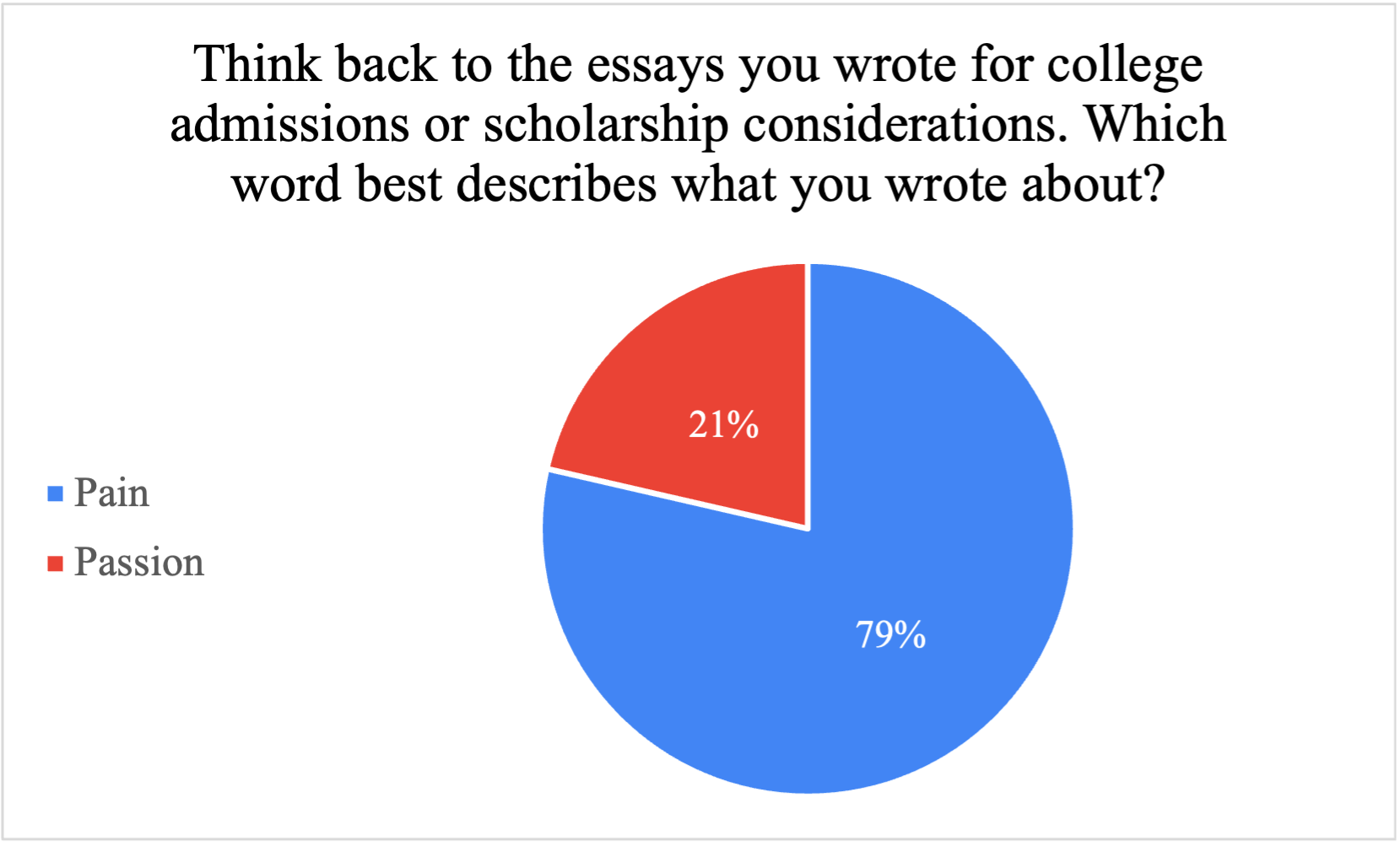

My research continues to support the claims that most Black students choose to write about something traumatic. 78% of survey participants say they wrote about a “pain” versus a passion. “I wrote my essay about the pervasive stereotype that Black men are not always available for their children,” says first-year student, Madison Brownt. “I wanted the university to view me as a resilient person. I wanted the admissions committee to see how I’ve persevered and moved past that to be successful.”

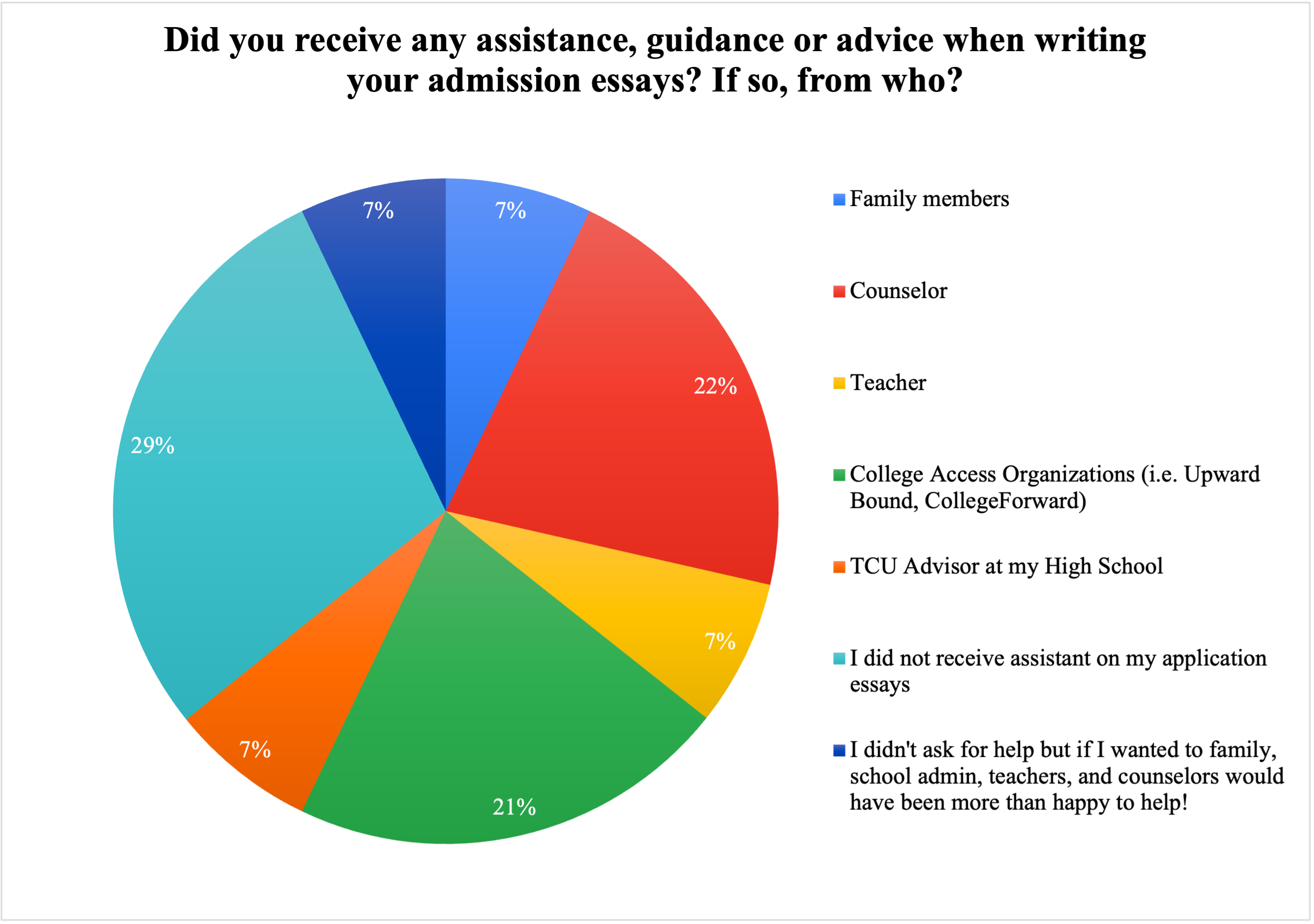

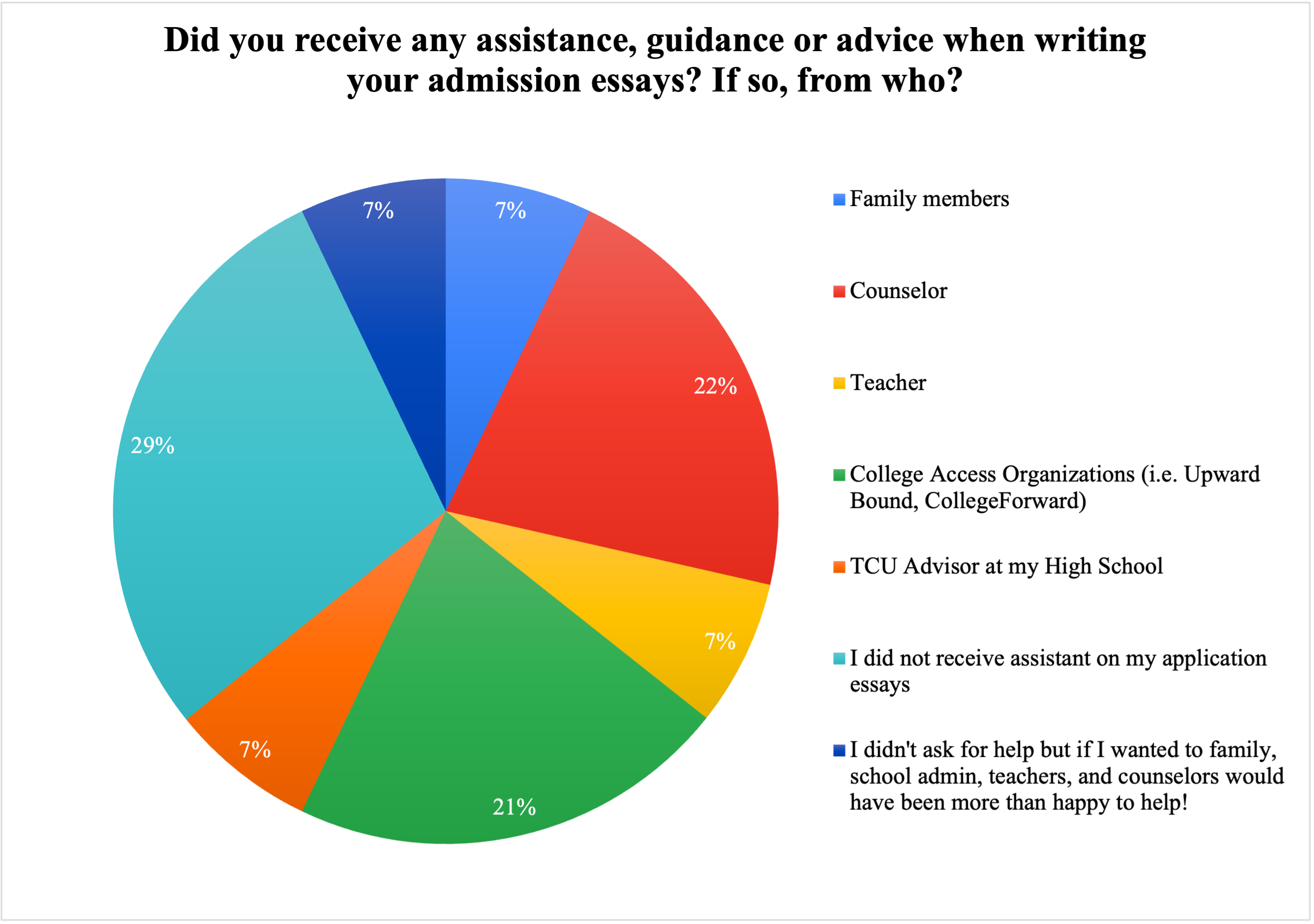

Something else that I found interesting was how most Black students did not receive professional help writing their essay. Instead, they heeded advice from family and counselors, which supports Waller’s theory on social actors. “I was guided by my advisor to discuss my lows in life to highlight why I should be awarded this scholarship,” says Grant.

Students who write about adversity do so to prove their worthiness. 42.9% of survey respondents find the essay about facing a challenge the ‘easiest’ to write.

“I wanted the admissions staff to take away that I am an individual who does not give up despite the circumstances,” says first-year student, Kennedi Grant. “I used my story to convey to them that I would work hard if given the opportunity.”

Doing so may have other implications: that they’re desperate to leave the situation they come from. That they need a savior to rescue them. This in turn creates a contentious dynamic between the student and their school, where they have internalized a narrative that is isolating. They may feel like an imposter, who is there for different reasons from everybody else.

“I think that TCU profits from my presence as a Black person,” notes Brown. “When I see people of color touring campus, I feel like an asset to the community, because seeing me might entice someone to come here.”

They may also become bonded to this version of themselves, since that version is the one that’s been validated.

But Brown, and other Black students alike, want to be valued for more than their ‘blackness.’

“My essay put me in a box. I think it reaffirms a lot of stereotypes about the Black community that are continually perpetuated in the media,” she says. “When I wrote the essay, I felt that those circumstances defined me, but now it is more of what made me instead what I am.”

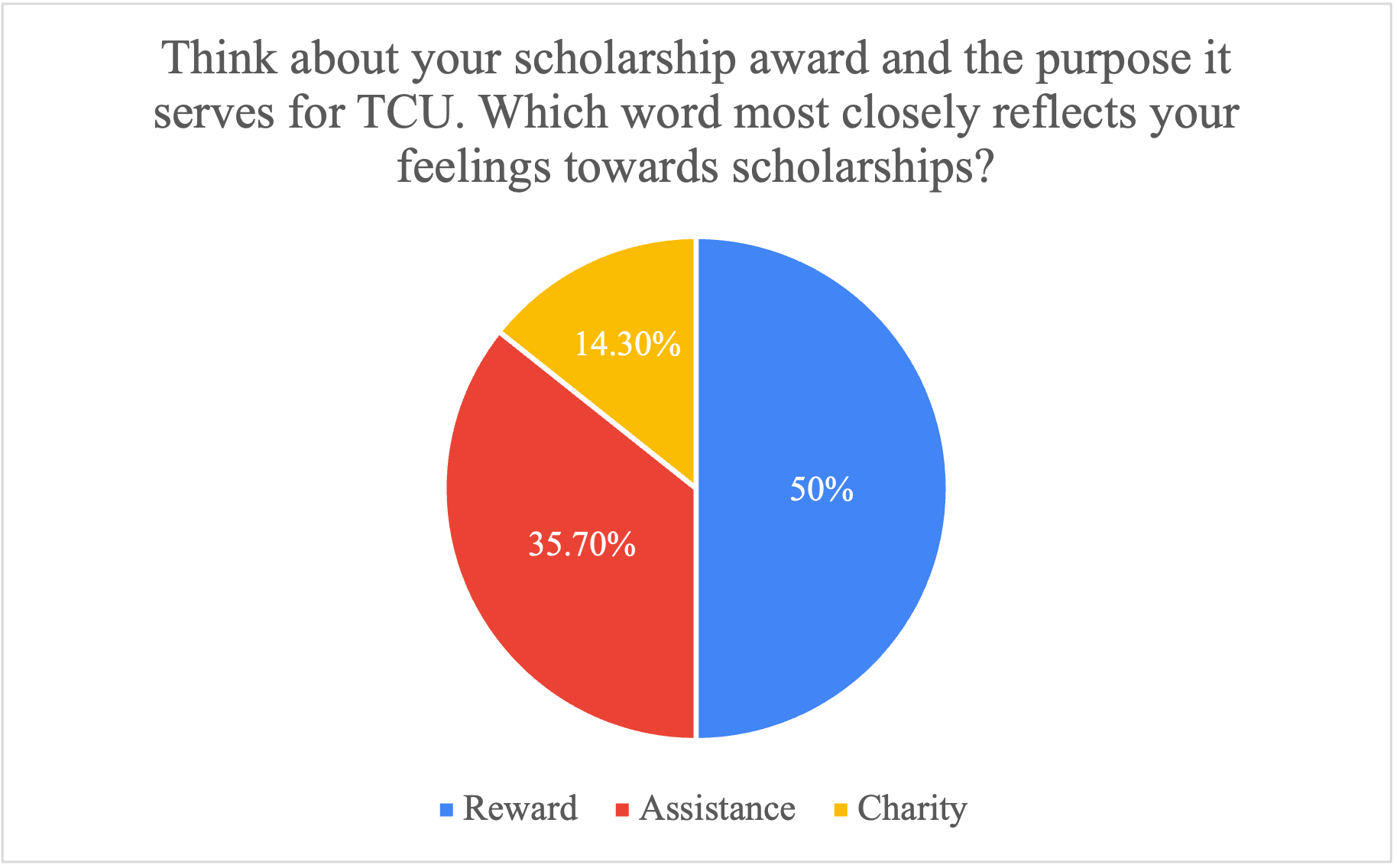

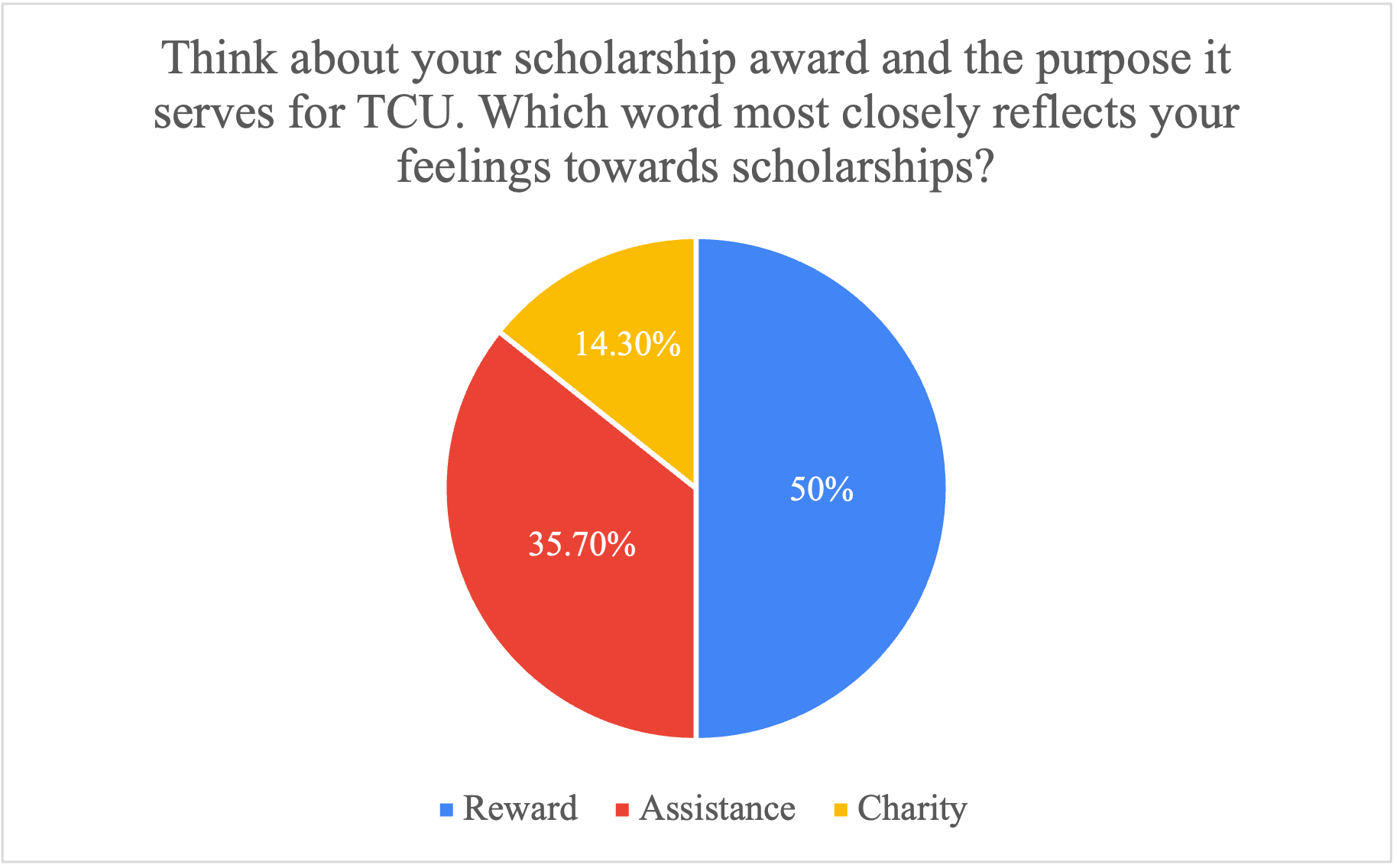

42.9% of respondents of the survey stated that they felt like a token of diversity on campus. And 50% of the scholarship recipients view their relationship with TCU as transactional.

“One of my professor’s said it best: University scholarships like the Community Scholar Program ‘pay’ students of color to educate their White peers and make them more culturally aware,” says senior participant, Haley Freeney. “[This] often comes at the expense of students of color. Students of color experience a lot of emotional turmoil being the “diversity” at a predominately white campus. The listening sessions during the 2019-2020 school year exemplify that.”

Freeney is referring to a series of open discussions held by university leadership as a short-term initiative to address “pressing needs” expressed by students. In a note to campus, Chancellor Boschini wrote to acknowledge the “clear gap” between the university’s intentions, its actions and what underrepresented students experience. He promised to “take the lead” on identifying ways the school can improve. And while it’s true that Boschini and campus administration were present for these sessions, many students still left without tangible solutions, and even three years later don’t see much change. Thus, the sessions appeared to be performative at best, and all at the expense of passionate students who shared vulnerable stories from their campus experience.

I think this best illustrates the relationship these students have with TCU: through the commodification of their trauma, their acceptance is conditional: In exchange for an education (with a price that’s often reduced), you must become an advocate, (activist), ambassador, and spokesperson (for your entire race.) You are here as a number for their demographic data, which is a seed that can be traced back to the admissions process and because it was planted before you even got on campus.

When I spoke to Meredith Lombardi, Director of Education and Training for Common App, she seemed to agree that there was a correlation between Black students and essays that is currently going unaddressed. While she says there’s little demographic data that’s been collected or released, she is encouraged by the conversations happening today.

"Moving forward, we want to learn more about who is choosing certain prompts to see if there are any noteworthy differences among student populations,” she said.

Conclusion

The things we write aren't just informed by our experiences–they shape how we view those experiences as well. And if we're writing about our trauma to prove to an admissions officer that we are worthy of a decent education, qualified for acceptance into their institution, then it becomes necessary to sanitize our pain – to make it marketable, strategic – to commodify it…and what’s the exchange? What do we, as students, receive in return for having exploited our experiences in order to be deemed worthy of acceptance? If by displaying the adversity we have faced, we are somehow being accepted in higher numbers, is this itself not indicative of a flawed system? Where is the line between effortful diversity and tokenism? Between earnestness and insincerity?

Waller established how racism attempts to reduce Black students to a single story. I looked at how labels are imposed upon the stories, and the way Black students interact with them. Admittedly, the problem goes much deeper than individual universities, and even perhaps the institution of higher education itself. It's rooted in the cultural obsession with consuming trauma, as well as a systemic tendency to tokenize people and their experiences.

The conclusion of this narrative poses a unique opportunity for post-secondary institutions to instead help these students ”re-write” their scripts without exploitation, tokenization, and perpetuation of stereotypes. They can do this by shifting the culture: by honoring the vast diversity of stories from their black and other underrepresented students. By giving them different prompts to write from. TCU is already taking steps in the right direction, providing short answer questions for their in-house application. This will allow students different options to choose from, and it also shifts the weight from the 500-word essay. Additionally, TCU is a pioneer in its “Freedom of Expression” optional component, where students can submit any expressive medium of their choice. Just in my time being in the office, I’ve seen students send in art portfolios, video performances, and even a decorated surfboard. Having something like this can shift the focus away from the essay as the only way to personalize a profile.

In virtually every institution, there are always going to be areas in need of improvement. Especially regarding diversity in higher education, we certainly aren’t anywhere close to perfection – and obviously, the application and admissions processes are a key part of that. But the needed change extends beyond the administration and the prompts they pose to you. The voice of the individuals affected by elements such as the ones discussed here is a key component of change. And for Black students, especially ones here at TCU, I encourage you to go beyond finding your voice. I implore you to use it.

College Board on Essays:

There has never been a rubric or criteria for the application essays - just a prompt and the word limit. When asked the question, “What is a well-written essay?” College Board responded with technical advice:

“Does the essay provide a direct answer to the essay question?”

“Did the student use effective word choice, syntax, and structure?”

“Does it contain correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling?”

"I was worried that if my essay was not unique, my academic accomplishments wouldn’t matter."

"I heard that this needed to help differentiate myself from other candidates. Also, I heard that I needed to make the essay filled with passion and the emotions"

"There are often discussions around race when I am the only minority in the room, so I become the face of the race in the classroom."

Survey