Living with dementia

Jim McLarty's dementia diagnosis brought heartache, loss and grief, and a new sense of purpose.

It also brought him to TCU.

Something was wrong.

The mistakes were mounting — driving to the wrong location for a meeting, forgetting what to include in a weekly report, struggling to analyze data.

Jim McLarty was working 14-16 hours a day to cover his difficulties. His doctor had him start a journal tracking his symptoms.

After a busy day that included two meetings, McLarty realized he could only remember half of each meeting; his notes were incoherent.

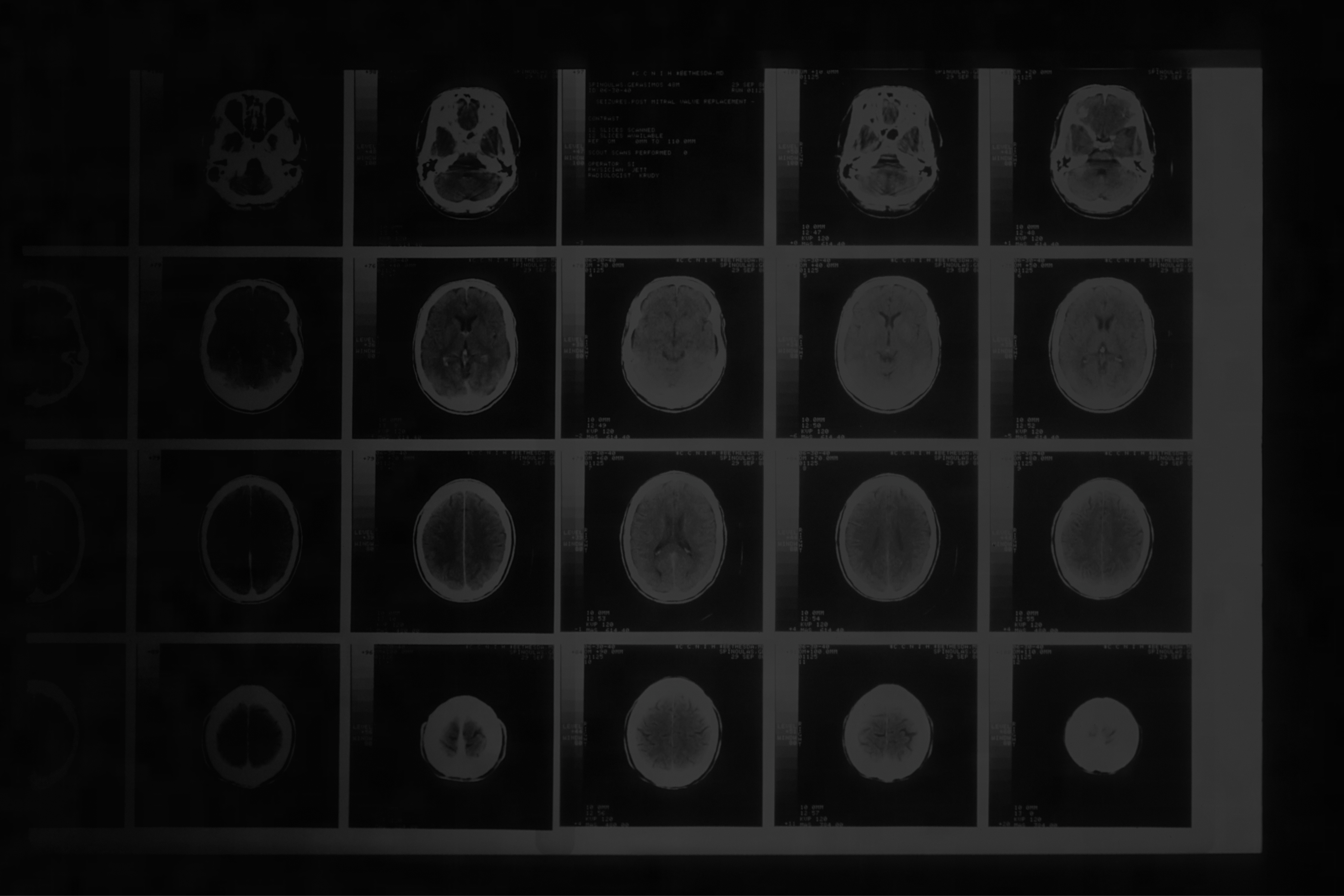

A referral to a neurologist brought a year of testing. Sometimes there were hours-long exams reminiscent of the SAT. Appointments filled with poking and prodding. Naps as an MRI machine whirred overhead.

The diagnosis: Binswanger’s disease.

Also known as subcortical vascular dementia, Binswanger’s is caused by the hardening, narrowing and breaking of arteries in the brain, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

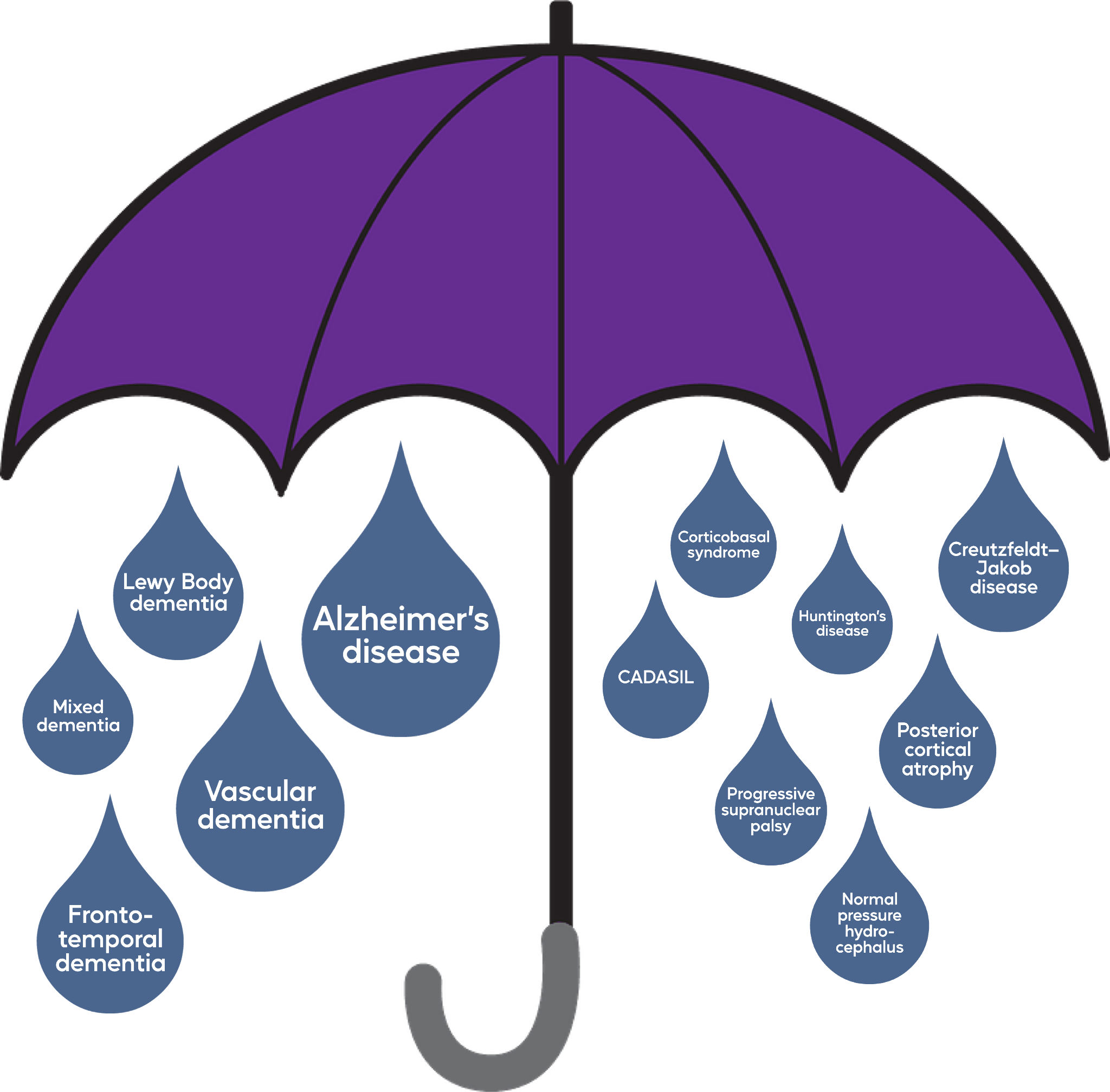

It’s nothing like the most recognizable form of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, which accounts for approximately 65% of cases of dementia. Most experienced medical professionals will never encounter Binswanger’s in their careers.

When he was diagnosed nearly six years ago, Jim’s wife, Nancy McLarty, said he could have been the poster child of Binswanger’s. He had every symptom: psychomotor slowness, short-term memory loss, an unsteady gait, declines in executive functioning and processing skills, mood swings and poor hand-eye coordination.

These and more symptoms form the “dementia umbrella,” which includes more than 100 diseases that cause dementia, such as Alzheimer’s or Binswanger’s.

The diagnosis gave a name to Jim’s struggle, but his journey was just beginning.

The dementia umbrella. (Sarah Walter/Staff Writer)

The dementia umbrella. (Sarah Walter/Staff Writer)

Finding purpose post-diagnosis

Jim’s doctor ordered him to medically retire from his career as a healthcare consultant.

He turned to his church community, but felt he lost a part of his sense of self. The quiet pace of retirement chipped away at his identity.

Then, he began learning more about his disease.

He participated in a research study on dementia health literacy. Through that study, he met Michelle Kimzey, a TCU nursing professor who studies and teaches about dementia.

Kimzey loved that Jim spent his entire professional life in healthcare, working his way up the hospital food chain from a 16-year-old orderly to Chief Nursing Officer.

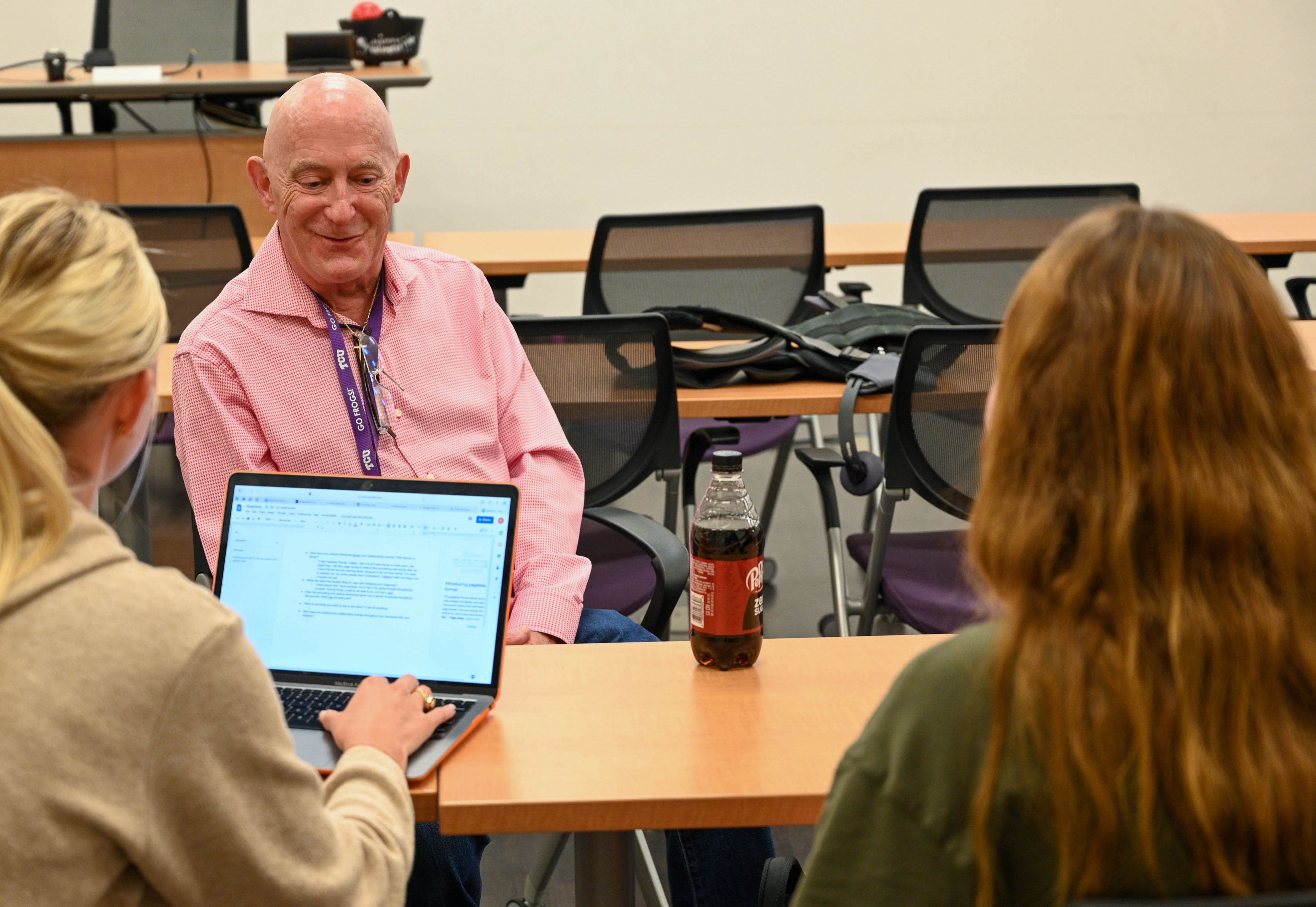

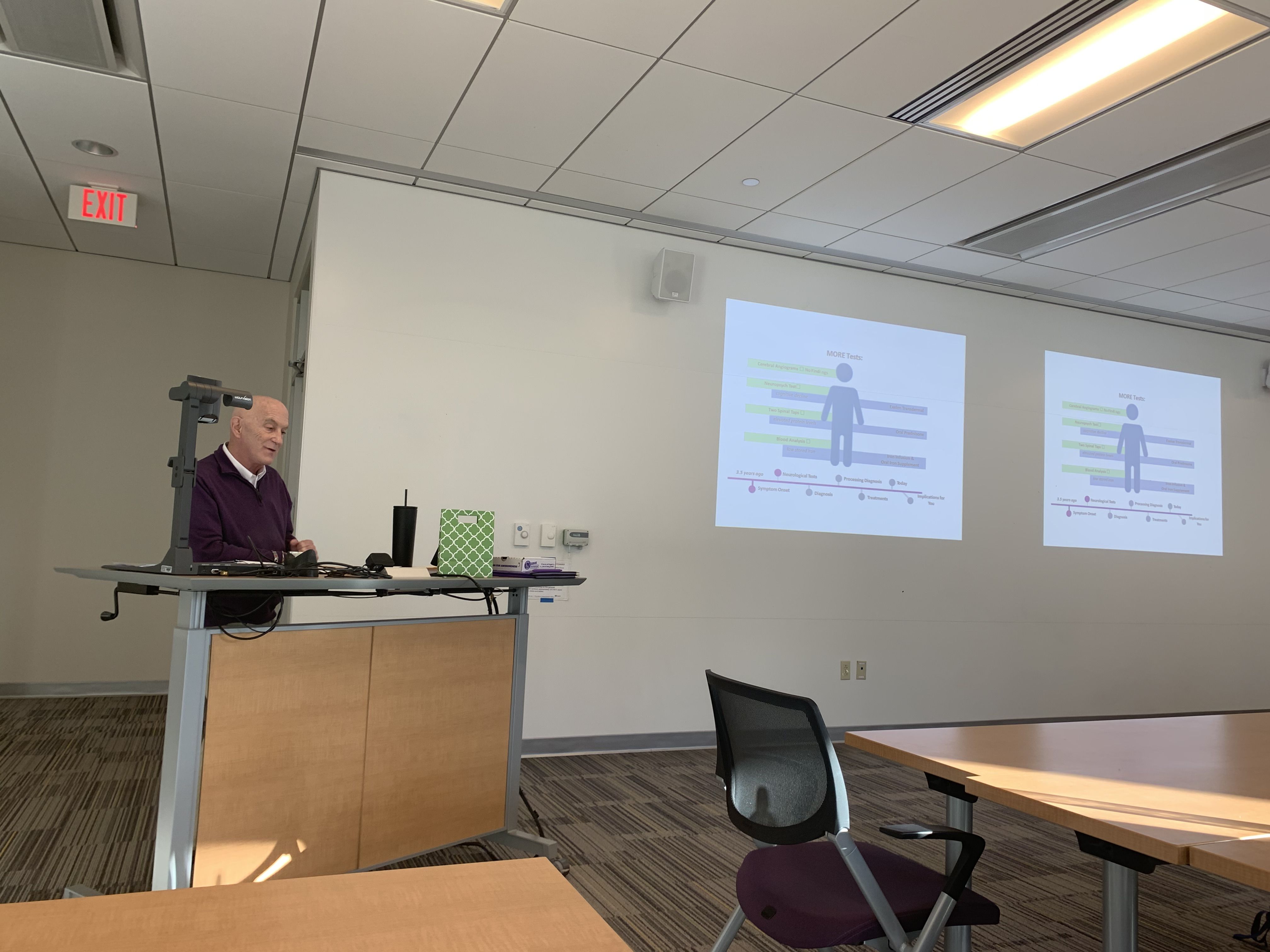

“Jim shares his expertise on whatever we’re talking about, whether it’s how you get diagnosed or how you’re treated,” Kimzey said. “Students really want to talk to him because he’s living it, and he was in the healthcare industry, so it’s beneficial to them.”

She asked him to speak to her class on dementia care in 2019. That 30-minute guest lecture evolved into teaching the course alongside Kimzey.

Jim explains his diagnosis and experience to the Dementia Care class in one of the first meetings of the semester. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim explains his diagnosis and experience to the Dementia Care class in one of the first meetings of the semester. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

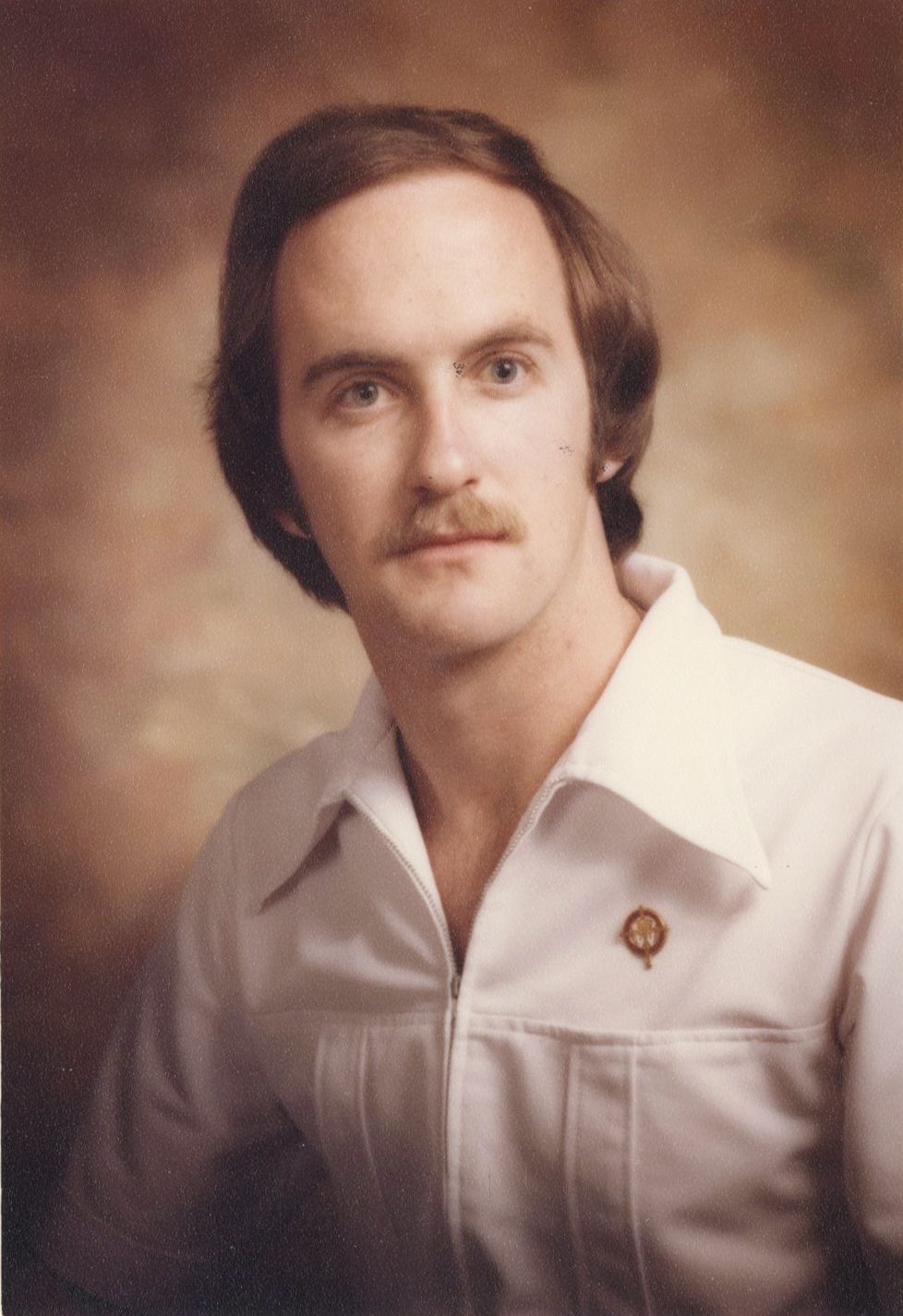

Jim McLarty's graduation headshot. He attended West Texas State University (now West Texas A&M), earning a Bachelor of Science in Nursing. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim McLarty's graduation headshot. He attended West Texas State University (now West Texas A&M), earning a Bachelor of Science in Nursing. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

It also led to interviews for podcasts, talks to churches, workshops and a seat on Rethinking Dementia’s board of directors.

“Because I was in nursing, I feel like I’m giving back some to my own profession and educating others because there’s so much missing around dementia,” said Jim. “I feel like this is a way for me to help others.”

Kimzey said initially many students are confused and wonder how someone with dementia has the mental capacity to teach. They found that he provides an authentic representation of an illness often portrayed negatively in the media.

“Having him in the class and lecturing lets us see for ourselves that you still are very capable of living a very fulfilling life even after being diagnosed with dementia,” said senior nursing major Tess Whitworth, who took Dementia Care in fall 2021.

Junior nursing major Devina Bueschel said the class and Jim made her rethink dementia.

“It helped me see that people with dementia are not defined by their diagnosis,” said Bueschel, who took Dementia Care last semester. “I thought a diagnosis meant you immediately stopped doing things like driving and learning new skills, but it doesn’t.”

Working the students helped Jim regain his professional identity.

'The long goodbye'

Dementia is often referred to as “the long goodbye.” It’s a drawn-out process, happening in stages with varying lengths and symptoms, as caretakers and loved ones prepare for their impending loss.

There’s no cure. Treatments can only slow cognitive decline or manage current symptoms.

“You know it’s going to end your life unless something else does,” Jim said. “It’s progressive and it’s terminal. It just typically is.”

Jim tries not to think about the end stages, but it’s difficult when he’s aware of every cognitive decline.

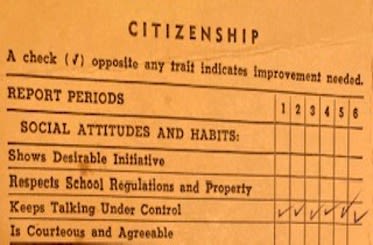

Jim's report card from fifth grade. He says it's fitting that with Binswanger's, language is one of the last skills to fade, since he's been a chatterbox his entire life. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim's report card from fifth grade. He says it's fitting that with Binswanger's, language is one of the last skills to fade, since he's been a chatterbox his entire life. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim and Nancy McLarty scuba diving prior to Jim's diagnosis. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim and Nancy McLarty scuba diving prior to Jim's diagnosis. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Although patients with Alzheimer's and other more common forms dementia often aren't aware they are losing skills, Binswanger patients maintain their awareness.

Jim said in the early stages the decline “stair steps.”

“You’ll drop, and then you’ll have a period of stabilization, and you’ll drop again,” he said.

Six years ago, Jim said the staircase was seemingly endless.

This year, the once far-off final steps have come into view.

“I don’t think there’s many more steps,” he said. “I’m just going to lose abilities.”

If you think about taking a bookcase and rocking it, the books at the top start falling out first. The books that fall first are your cognitive abilities, your executive functions. More books fall out as the shelf goes down, so you’re losing more and more of those abilities. At the bottom represents your feelings and who you are as a person. Those are the things that are the last to go, if they ever leave.

Rising above the noise

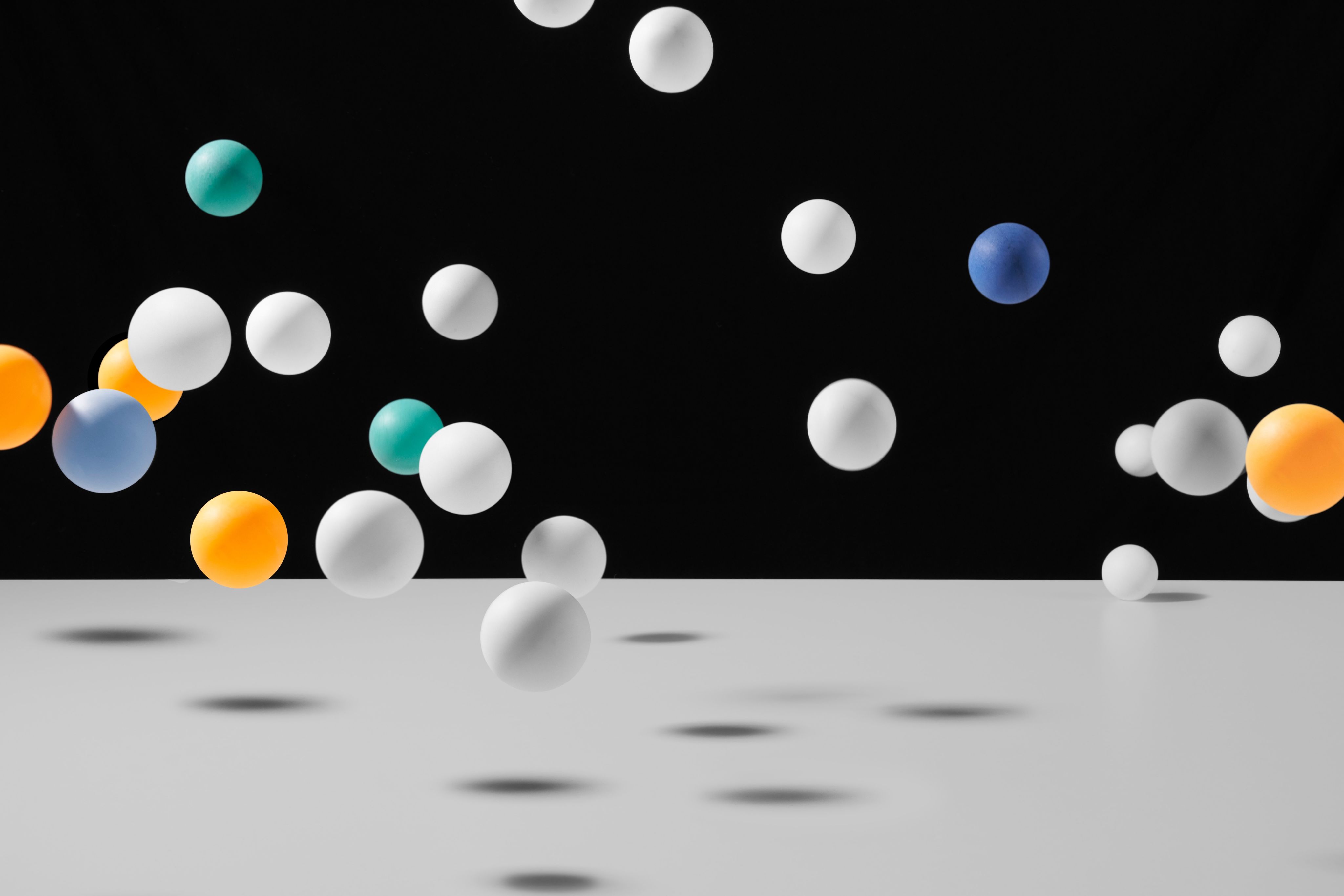

Jim said his brain feels like it’s filled with ping pong balls moving at breakneck speed, a cacophony of clashing and clanging.

To read, to write, to speak, to think, he has to “rise above the noise.”

Some days are worse than others.

Some days, the noise is a distant hum, barely audible as he plays video games with his grandson or meets with his Bible study group.

Other days, the noise is a jackhammer chiseling away at Jim’s composure. He’ll walk into a room and forget why he entered, what he needed to accomplish. Sometimes the task will come back to him minutes or hours later. But many days, it doesn't.

Nancy calls those his fuzzy days.

“Those seem to happen more and more now,” Jim said.

People always say Jim doesn’t seem like he has dementia.

He doesn’t fit the stereotypical or Hollywood image of someone who is nonverbal, using a wheelchair, unresponsive, unable to recognize family members — someone who isn’t entirely “there.”

A body, but not a person.

Jim can still recall the exact number — 64 — of students in his high school graduating class; he’s taken up tandem skydiving since his diagnosis; he regularly speaks to groups about dementia; and he hiked an active volcano in Iceland last year.

Jim and Nancy McLarty hike in Iceland. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim and Nancy McLarty hike in Iceland. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim McLarty and Jan (Nancy's best friend) in Antarctica in 2019. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim McLarty and Jan (Nancy's best friend) in Antarctica in 2019. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim McLarty sky dives with an instructor. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

Jim McLarty sky dives with an instructor. (Photo courtesy of Jim McLarty)

There’s not one way dementia “looks,” he said. It’s a disease as diverse as the people who have it, as varied as their life experiences.

He knows he will progress to being nonverbal or requiring a wheelchair, but that won't mean he isn't there.

"It makes me feel sad when people say, 'there's just a body there,'" he said.