How Tarrant Regional Water District reuses and recycles

George Shannon Memorial Wetlands Water Reuse Project

To accommodate a growing North Central Texas population in the late 20th century, a new reservoir was needed. The rural area of Corsicana, about 100 miles southeast of Fort Worth, was chosen. Ranches would be purchased. The Richland and Chambers Creeks would be flooded.

About 50,000 acres would be disrupted or eliminated, according to the final environmental impact study of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, including almost 30,000 acres of farm and ranch land.

Seventy miles of creeks and streams were inundated; 37,000 acres of wetlands and flood plain were affected, according to the environmental impact study. More than 80,000 natural habitats were lost, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Department estimates.

The Richland-Chambers Reservoir was born. It opened in 1989 and covers about 40,000 acres. The lake has a total capacity of holding more than one million acre feet of water, according to a 2007 survey by the Texas Water Development Board.

Water, water everywhere

The Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area was created to counterbalance the environmental losses caused by the construction of the reservoir. Tarrant County Water Control and Improvement District No. 1 bought 13,000 acres of unaffected creek bottomland and donated them to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to own and operate.

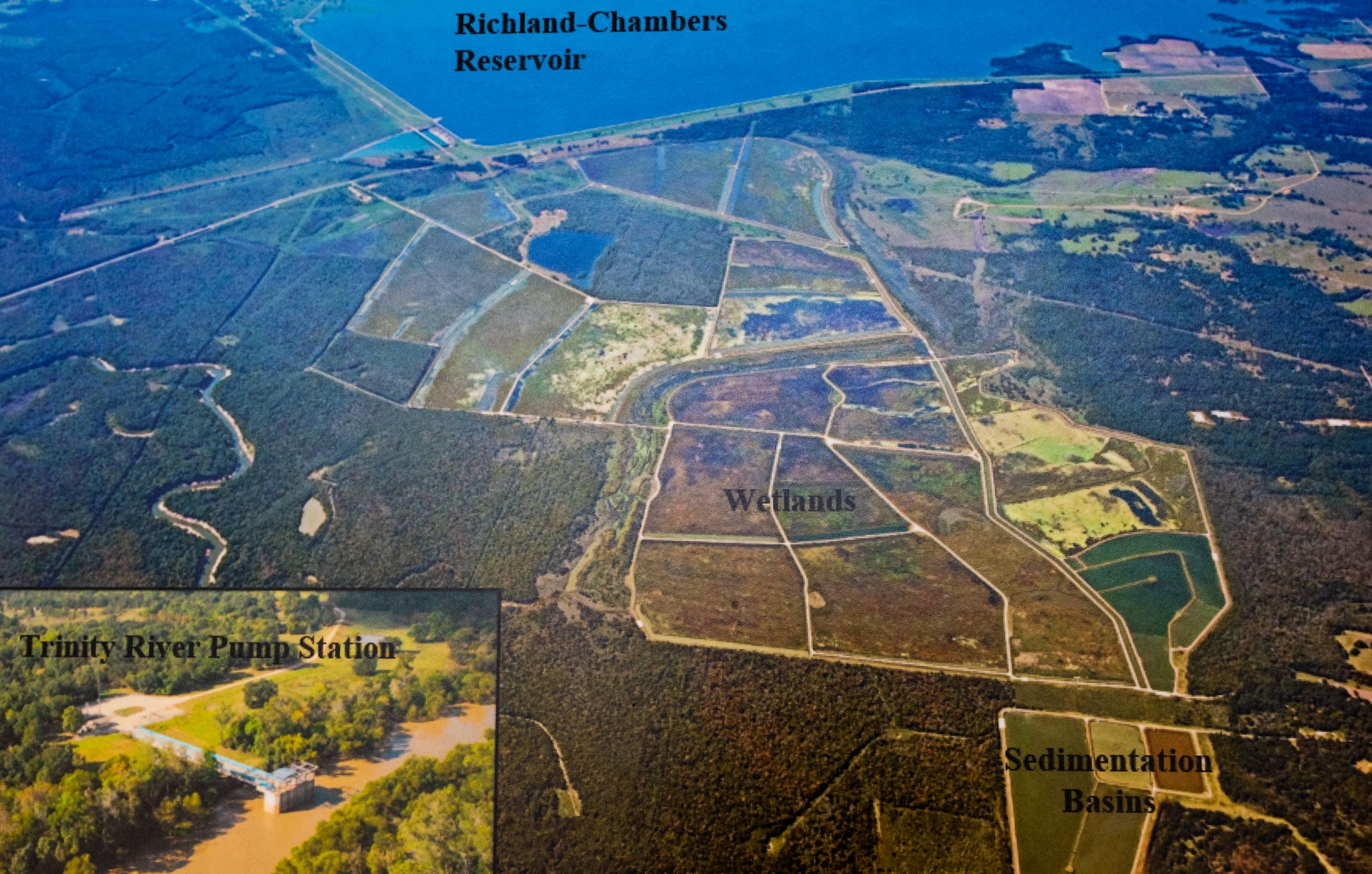

The award-winning George Shannon Memorial Wetlands Water Reuse Project is in the middle of this wildlife refuge. The 2,000-acre manmade wetlands straddle the Navarro County and Freestone County line. It is the first wetlands built to increase water supply, according to the Tarrant Regional Water District (TRWD).

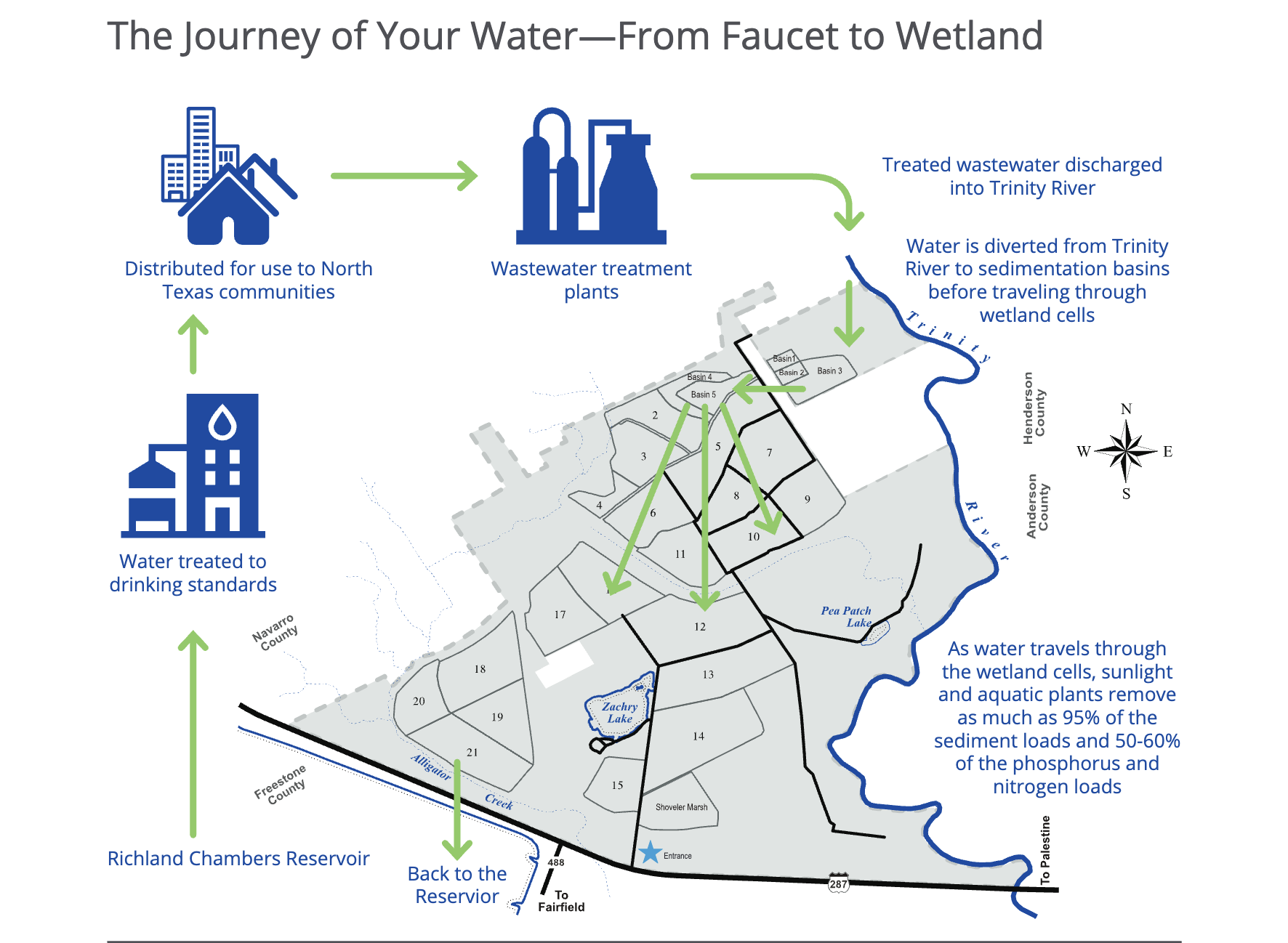

It was created to protect delicate ecosystems and naturally filter wastewater pumped from the Trinity River. The river water is considered wastewater since it consists of runoff and discharged water from rural areas and municipalities upstream.

"We’re taking wastewater, and we’re reusing it, repurposing it, filtering and cleaning,” said Hagen Keele, a TRWD environmental specialist, who works at the wetlands.

The George Shannon Wetlands started as a pilot program on seven acres in a different location in 1992 to determine the feasibility on a larger scale, said T. Wells Shartle, another TRWD environmental specialist at the wetlands . The current wetland system at Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area was built between 2000 and 2013, completed in three phases.

The murky Trinity River water is directly drawn into a pond or "cell" system, formed by levees and controlled by pumps, valves and weirs. In these cells, the water is naturally filtered and cleaned by gravity and aquatic plants that remove pollutants.

After environmental filtration, the water is pumped into Richland-Chambers Reservoir, just one of several water sources for TRWD. The agency is a water wholesaler that sells “raw” water to communities in 11 North Texas counties. Municipalities then treat and process it for drinking.

The Trinity River rises over its banks at the George Shannon Wetlands pump station April 14, 2024. During the rainy months, the pumps are offline. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

The Trinity River rises over its banks at the George Shannon Wetlands pump station April 14, 2024. During the rainy months, the pumps are offline. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

The wetlands are divided into five sedimentation beds and 20 manmade cells or ponds that gradually descend in elevation, using gravity to keep the water flowing. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

The wetlands are divided into five sedimentation beds and 20 manmade cells or ponds that gradually descend in elevation, using gravity to keep the water flowing. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Six 250-horsepower pumps draw water from the Trinity River. Pipes carry the murky water into the wetlands' sedimentation basins. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Six 250-horsepower pumps draw water from the Trinity River. Pipes carry the murky water into the wetlands' sedimentation basins. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Cleaned by Mother Nature

The first stop for the river water is a series of five sedimentation basins covering 117 acres. These ponds rely on gravity to naturally filter 95% of sediment like dirt and silt to keep it out of the river downstream, said Keele.

Then, water naturally flows into 20 cells with gradually lower elevations. The water gently, almost imperceptibly, flows through weirs under earthen levees dividing the ponds. Because water is always moving, mosquitos are not a problem.

Water channels six feet deep ensure that each cell maintains a consistent six- to 12-inch layer of water, Keele said. Otherwise, the system would "short-circuit," and the water would flow as a creek. "All water gets touched by plants," he said of the wetlands cell system.

Aquatic plants growing in the ponds naturally extract 50-60% of phosphorus and nitrogen. Bulrush, pickerel weed, water clover, grassy arrowhead and many others thrive in marshy environments and clean the Trinity River water.

“These plants take up nutrients held in the river and also provide a habitat for the micro- and macro-organisms to live in,” Keele said.

He and co-worker Shartle test the water quality weekly when the wetlands are fully functional. These are vital readings for the engineers to know the stability of the water inside the pipes, said Keele.

After seven to 10 days, the cleaned water is held in a "treated-water canal" before getting pumped into the reservoir. When operational, the George Shannon Wetlands can add 95 million gallons a day to Richland-Chambers, according to the Tarrant Regional Water District.

The wetlands go offline during flooding and when the lake level is at or near 100%, Keele said. During a rainy season, thousands of gallons of water jettison over the spillway into the Trinity River. The wetlands in the dry year of 2023, he said, functioned for 56 straight weeks. He estimates the wetlands will be back in operation again by midsummer.

See what the George Shannon Wetlands looks like when it's fully operational and all the wildlife that depends on it. Courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

Hagen Keele, an environmental specialist at the George Shannon Wetlands, points out features in a sedimentation basin March 17, 2024. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Hagen Keele, an environmental specialist at the George Shannon Wetlands, points out features in a sedimentation basin March 17, 2024. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Deep water trenches or zones help maintain 12" water levels in the cells when they are full and operational. During wet months, the wetlands' purification system goes offline and water is allowed to evaporate. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Deep water trenches or zones help maintain 12" water levels in the cells when they are full and operational. During wet months, the wetlands' purification system goes offline and water is allowed to evaporate. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Keele says he remembers to wear gloves working the valves that control the weir gates and flow of water between cells. Raccoons wait for crawfish as they swim over the gates. Sometimes the wheels are covered with remains of their crawfish dinners. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Keele says he remembers to wear gloves working the valves that control the weir gates and flow of water between cells. Raccoons wait for crawfish as they swim over the gates. Sometimes the wheels are covered with remains of their crawfish dinners. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

When the system is operational, naturally treated water cascades from the George Shannon Wetlands into Richland-Chambers Reservoir down concrete steps. The wide disbursement helps oxygenate the water, Keele says. Photo courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

When the system is operational, naturally treated water cascades from the George Shannon Wetlands into Richland-Chambers Reservoir down concrete steps. The wide disbursement helps oxygenate the water, Keele says. Photo courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

The concrete steps into Richland-Chambers Reservoir are dry when the wetlands are offline on March 17, 2024, because of the lake's full capacity. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

The concrete steps into Richland-Chambers Reservoir are dry when the wetlands are offline on March 17, 2024, because of the lake's full capacity. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Thousands of gallons are released from Richland-Chambers Reservoir into the Trinity River on March 17, 2024. Video by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Thousands of gallons are released from Richland-Chambers Reservoir into the Trinity River on March 17, 2024. Video by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

Courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

The Nature of the Wetlands

Grassy arrowhead covers most of this cell at the George Shannon Wetlands. The aquatic plant is a food source for ducks, geese and nutria, according to Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Photo courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

Grassy arrowhead covers most of this cell at the George Shannon Wetlands. The aquatic plant is a food source for ducks, geese and nutria, according to Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Photo courtesy of Tarrant Regional Water District.

Diverse ecosystems

TRWD has an agreement with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Keele said, to set aside one third of the cells for maintenance between March and September. It's part of the moist-soil management program that manmade wetlands practice.

It "resets the vegetative communities" and enables healthy, diverse ecosystems for plants and wildlife, particularly for waterfowl, Keele said.

Creating a healthy food chain is important for a substantial duck population. If it wasn’t for the wetlands, mallards, herons, coots and other waterfowl would not be there, said Keele. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Creating a healthy food chain is important for a substantial duck population. If it wasn’t for the wetlands, mallards, herons, coots and other waterfowl would not be there, said Keele. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Winging it

The wetlands are a popular stopover for migrating and wintering avian flocks. It's a favorite destination for birdwatchers and hunters.

Texas Parks and Wildlife opens the area to hunting during the season through a lottery system for ducks, deer, dove, rabbits, squirrels and feral hogs. Check the website for special hunting rules and requirements.

Feral hogs wallow in the muddy cells, disrupting smooth operations at the George Shannon Wetlands. Photo by Sally Verrando/ TCU 360 photographer.

Feral hogs wallow in the muddy cells, disrupting smooth operations at the George Shannon Wetlands. Photo by Sally Verrando/ TCU 360 photographer.

Hog wash

Wild hogs wallow in the partially evaporated cells and churn up mud. Tractors smooth out the pitted surfaces when the mud dries, said Keele. Since feral swine are considered invasive, hunting them is permitted.

Nutria and beaver also are destructive. They clog up weirs and burrow into earthen levees, accelerating erosion that can wash out roads, Keele said.

Alligators are at home in the George Shannon Wetlands. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Alligators are at home in the George Shannon Wetlands. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

That's no log

Some aquatic critters find their way into the wetlands and eventually to the reservoir. Fish, frogs and alligators get sucked into the pipes from the Trinity River and travel through the cell system.

When visiting, be aware that alligators swim in the ponds and sun themselves on the grassy banks and gravel roads.

Keele’s formula for calculating the length of an alligator: Estimate the inches from its nostrils to its eyes then substitute feet for inches to get the overall length.

Animal tracks cross a muddy pond bottom at the George Shannnon Wetlands. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Turkey and black vultures are numerous at the wetlands. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Camping

Birders, hunters and outdoor lovers can camp at the Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area but they should come prepared. There's no electricity on site. Fresh water, food and restrooms are miles away.

The area is prone to flooding so watch the weather and be ready to move to higher ground.

Leashed dogs are welcomed for campers and day-use guests.

The entrance to the Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area off U.S. Highway 287, east of Corsicana. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

The entrance to the Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area off U.S. Highway 287, east of Corsicana. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Yellow gates keep visitors out of hazardous areas. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Yellow gates keep visitors out of hazardous areas. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Roads close, as well as the whole operations of the wetlands, when the Trinity River floods, as on April 14, 2024. Even though the cells were filled with untreated river water, another purpose of the wetlands is flood control. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

Roads close, as well as the whole operations of the wetlands, when the Trinity River floods, as on April 14, 2024. Even though the cells were filled with untreated river water, another purpose of the wetlands is flood control. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

An abundance of wildflowers grow in the Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area on April 14, 2024. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

An abundance of wildflowers grow in the Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area on April 14, 2024. Photo by Sally Verrando/TCU 360 photographer.

So good the first time: more wetlands on the way

Another wetlands development is planned for Cedar Creek Lake, 10 miles east of Ennis, near Richland-Chambers Reservoir. The new reuse water project is expected to cover more than 3,000 acres.

Construction is due to start in 2026 once the land purchases and permit process are complete. It should be functional by 2032, according to Tarrant Regional Water District, and is expected to produce more than 150 million gallons of cleaned water daily. That will provide water for an another 1.1 million people.

Wetlands are cheaper than building new reservoirs and are better for the environment, said Keele. They create habitats for ducks, eagles, alligators and other wildlife.

Who was George Shannon?

George West Shannon (1937-2005) was board president of the Tarrant Regional Water District for 15 years. The construction of Richland-Chambers Reservoir and the wetlands reuse water project were just two ventures under his guidance to improve the water supply for Tarrant area residents. He oversaw connecting Lake Benbrook to the Tarrant region's water supply. Shannon also helped develop the Trinity River Vision Plan, a master-plan development that included the Trinity Uptown project for revitalizing the City of Fort Worth.