Firearms killed dozens of Fort Worth kids in recent years.

A doctor, a detective and a researcher say guns aren't the problem

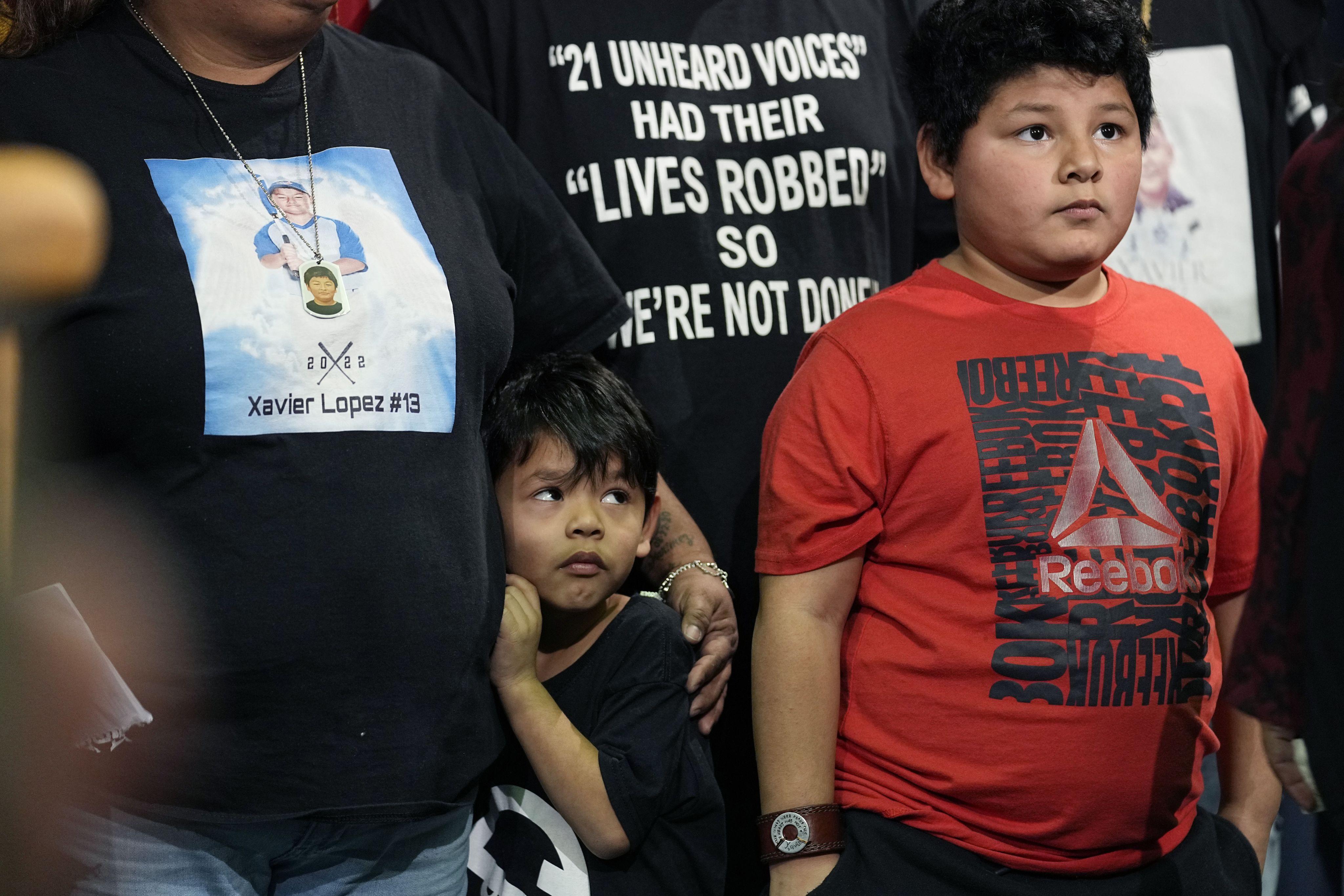

In the past five years, 38 children in the City of Fort Worth have died from gunshot wounds, according to the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office.

Most of them were homicide victims, some of them died of suicide. Only one was an accident.

Dr. Dan Guzman has been a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Cook Children’s Medical Center for 22 years. Guzman said the fast-paced nature of life in the emergency room and his love for children drew him to the field.

“There’s always something different around,” Guzman said. “That’s my personality.”

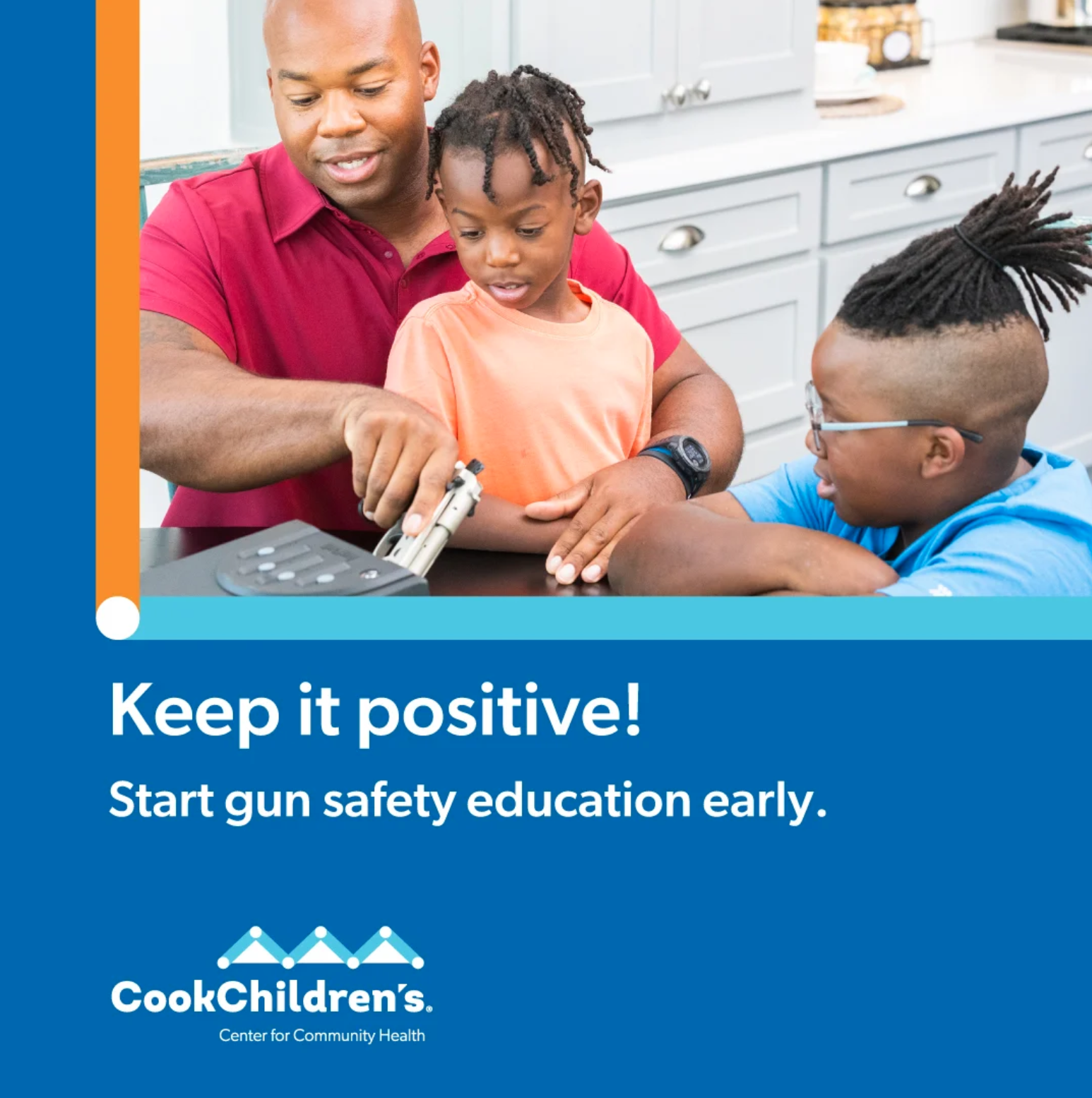

Over the past seven years, he said, his experiences as a doctor led him to become a “champion” of injury and violence prevention. In addition to his medical practice, Guzman is in charge of Aim For Safety, the gun violence prevention program at Cook Children’s.

The idea for the program came out of a tragedy: Guzman treated a four-year-old patient who had been accidentally shot by his six-year-old brother when the two found their mother’s unsecured firearm in their home.

He and his team could not save the child’s life.

“That day was the point in my life where I was like, I need to do something,” he said. “I have a platform, I have an opportunity.”

In building the program, Guzman said he wanted to keep the focus on child safety instead of firearms.

The polarizing nature of firearm-related topics, especially in Texas, means that when the conversation focuses on guns, the discussion can quickly devolve, he said.

“It’s not a political statement, we’re not taking a stand,” he said. “Because then you lose the audience that is really most impacted in many ways by this.”

Aim For Safety’s website provides everything from facts and data to educational resources and conversation starters for parents looking to talk to others about the presence of guns in their homes. Additionally, through funding provided by Cook Children’s, the Aim For Safety program provides gun safes and gun locks to families who own firearms.

Guzman is also conducting a research study that focuses on the way children behave around unsecured firearms.

During the study, children between the ages of four and 12 are placed in a room with three non-functional firearms and observed for 15 minutes.

“The standard teaching is that you don’t touch a firearm, you walk away from it and you tell somebody,” he said. The majority of children who participated in the study did not follow that guideline.

Of the children he observed, 80% either stayed quiet, picked up the firearm or looked down the barrel, Guzman said. The remaining 20% came to find adults and tell them about the weapon.

“I wanted, in a non-confrontational way, to show parents that this is what happens when your child is around a gun,” he said.

If the parents involved in the study do not have a safe way to store their firearms, Guzman provides them with a lockbox.

He follows up 30 days later to see if the parent is using it.

The overarching theme of his work in preventing pediatric firearm injuries, Guzman said, is to make it known that no one is immune to tragedy.

“The bullet doesn’t care, when it comes out of the barrel, about what it’s going to hit,” Guzman said. “Your child might get lucky 99 times out of 100, but it just takes one time.”

The impact of gun violence on children is not limited to injury and death: a 2023 study shows that participants who witnessed gun violence prior to the age of 12 were more likely to carry a gun in their adolescence.

One of the study’s co-authors, TCU criminal justice professor Benjamin Comer, said the study was motivated by a lack of meaningful research on the impact of gun violence on individuals over time.

Comer’s study used data from the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, or the NLSY 97.

The NLSY 97, an ongoing research study that began in 1997, collects data annually on individuals born between 1980 and 1984. The survey monitors participants in areas of childhood, marriage and family, income, health and crime and substance use.

In the same year that the NLSY 97 began collecting data, the U.S. government instituted a ban on federal funding for gun violence research known as the Dickey Amendment.

“The Dickey Amendment caused havoc, essentially, in funding for gun violence research,” Comer said. “Because of that, you saw really minimal gun violence research happening for quite some time.”

Comer’s study found that odds of handgun carrying among young people are highest in the immediate aftermath of witnessing gun violence. Over time, the likelihood decreases.

“If you find that violence exposure before the age of 12 is associated with higher odds of carrying a gun, subsequently any policy initiative should focus on reducing violence exposure,” Comer said.

In his single year with the Fort Worth Police Department’s Gun Violence Unit, Detective Kenneth D’Loughy has investigated so many cases that he can’t possibly recall them all.

Luckily, D’Loughy said, he doesn’t recall a lot of instances where children were the victims. On the contrary, he remembers more cases where children were the perpetrators.

Last summer, D’Loughy investigated a case on Fort Worth’s Northside: two juveniles shot a man in the stomach after an altercation at a convenience store near a public park. The victim survived, and the juveniles were later arrested at an Academy Sports and Outdoors location in White Settlement as they attempted to purchase more ammunition.

Most of the cases the unit deals with come out of the north side, which has a large population of Hispanic people or Fort Worth’s predominantly Black south side, D’Loughy said.

Part of the problem with teenage gun violence, D’Loughy said, is that social media makes it easy to buy and sell weapons quickly and virtually untraced.

“Social media is one of our biggest hurdles, because the kids are buying and selling these guns on Instagram,” D’Loughy said. “We can get a search warrant and get into these kids’ profiles to see what they’re doing, but by the time we do that, the gun’s already been sold.”

Younger kids are also more susceptible to commit acts of gun violence out of emotion or because of what they’ve seen on social media, D’Loughy said.

Still, D’Loughy supports the constitutional right to keep and bear arms. Like Guzman, the 17-year law enforcement veteran believes the focus needs to be on firearm safety.

“I think a lot of people fail to realize that firearms are also a giant responsibility,” D’Loughy said. “You have to safely secure them if you’re going to have them in a home where there’s children and especially teenagers.”

For Comer, D’Loughy and Guzman, the issue has never been with the firearms. All three men stressed the importance of safety, of creating environments less prone to violence, of how education and resources can change the outcomes for kids at risk.

“We want to save children’s lives because of what we see,” Guzman said. “I think it’s as simple as that.”

With thanks to the staff of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, whose endless support made this project possible.